The Wright Stuff

In a new biography of the brothers who invented the airplane, David McCullough describes the frustrations and triumphs involved in getting aviation off the ground.

A version of this article appeared in the Autumn 2015 issue of strategy+business.

What if you demonstrated a world-changing invention and nobody noticed? For years, that was the fate of the two self-taught men who pioneered a quantum leap in human transportation.

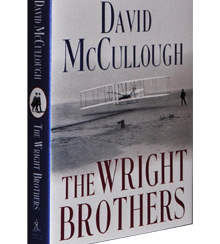

On December 17, 1903, on the windy Outer Banks of North Carolina, Wilbur and Orville Wright made four short flights in a crude flying machine that they had built in their bicycle shop back in Dayton, Ohio. Totaling less than 1,500 feet and witnessed by only five men (three of them from a nearby life-saving station in Kitty Hawk), the flights were a signal achievement in human history. “Their flights that morning were the first ever in which a piloted machine took off under its own power into the air in full flight, sailed forward with no loss of speed, and landed at a point as high as that from which it started,” writes David McCullough in his new biography The Wright Brothers (Simon & Schuster, 2015).

The story of how the Wright Brothers mastered the challenge of powered flight is a fascinating one, and as you might expect from a writer and historian of McCullough’s stature, it is told well and in detail. McCullough, the dean of popular historians and the author of landmark books on engineering feats such as the Brooklyn Bridge and the Panama Canal, describes how the brothers constructed their planes by trial and error — hand-shaping the propellers and the wings, and, with the help of Charlie Taylor, their sole employee at the bicycle shop, machining a simple gas engine from a block purchased from the Aluminum Company of America (now Alcoa). They then taught themselves to fly. They never flew together, lest they both die in a crash and fail in their quest.

It’s a story of human ingenuity that I remember reading as a boy, and it is no less inspiring decades later. But, as McCullough pointed out in a talk he gave in Kitty Hawk last fall, the really odd thing about it is that for years after those first flights in 1903, no one appeared to notice or care that two bicycle mechanics had actually achieved the age-old dream of flight (and on a shoestring budget of less than US$1,000). Certainly aviation was newsworthy: from 1898 to 1903, the Smithsonian Institution and the U.S. Department of War had sunk $50,000 into a failed effort at powered flight, and several European governments were also pursuing aviation projects. But even though the newspapers picked up the story (from a telegram the brothers sent home to their father and sister), the world did not beat a path to their door.

No one appeared to notice that two bicycle mechanics had achieved the age-old dream of flight.

Instead, the brothers returned to Dayton virtually unheralded. They continued to build and sell bicycles, and invested their profits in the ongoing development of their Wright Flyer. To save money, they stopped traveling to the Outer Banks for test flights and began using a cow pasture outside Dayton, which they rented from a local banker who thought them “fools.”

In January 1905, with more than 105 flights under their belts, the brothers sent a letter offering their invention to the U.S. Department of War. They promptly received a standard letter of rejection. In October 1905, by which time they were routinely making flights of 25 miles and more, they again offered the Flyer to the War Department. Again, their offer was rejected.

It wasn’t until the end of 1905 — two years after their first powered flights — that the Wright Brothers were finally able to make a deal for their invention. A representative of a syndicate of French businessmen traveled to Dayton and agreed to purchase a Flyer as gift to the French government. “According to the agreement,” McCullough writes, “the brothers were to receive one million francs, or $200,000, for one machine, on the condition that they provided demonstration flights, during which the machine fulfilled certain requirements in altitude, distance, and speed.”

Even then, it took the Wright Brothers another two-and-a-half years to win widespread recognition for their feat. In the summer of 1908, Wilbur flew at Le Mans in order to fulfill the terms of the French contract. Suddenly, the entire world recognized the brothers’ achievement. Almost five years after their first flights, the two became celebrities overnight.

Unfortunately for aspiring entrepreneurs seeking insights on how to commercialize technological breakthroughs, that’s pretty much the end of the story for McCullough — he sums up most of the rest of the brothers’ lives in an epilogue. In 1909, they formed the Wright Company, but ended up devoting most of their energies to filing and fighting patent suits. Wilbur died of typhoid fever in 1912 at age 45, leaving an estate of approximately $300,000. Orville sold the company in 1918, just a few years after airplanes were first used by military forces in World War I. When he died in 1948, his estate was valued at just over $1 million.

“On July 20, 1969,” concludes McCullough, “when Neil Armstrong, another American born and raised in southwestern Ohio, stepped onto the moon, he carried with him, in tribute to the Wright brothers, a small swatch of the muslin from the wing of their 1903 Flyer.” That’s a nice bit of recognition. But it seems short shrift for ushering in a technological revolution that changed the world and spawned an industry that will generate about $240 billion in sales in the U.S. alone this year.