Best Business Books 2015 — In Pictures

This photo gallery is part of the article “Best Business Books 2015.”

History has come pretty close to reaching a verdict on BlackBerry, the Canadian company formerly known as Research in Motion, whose devices were once considered so addictive they were known as “CrackBerries.” The simple story is that BlackBerry was rendered irrelevant by the iPhone. But the story that the authors, Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff, tell in Losing the Signal — our choice for the best book of 2015 on business narratives — is more complicated. The company was created by an unlikely duo: Jim Balsillie, a driven and paranoid salesman, and Mike Laziridis, a technical genius. Outside work, the two had nothing in common. Losing the Signal makes for painful reading as the company once again races to put out a product that can compete with the iPhone on a schedule that engineers tell the bosses isn’t possible.

George Bodenheimer’s Every Town Is a Sports Town, our choice for this year’s best book on leadership, falls squarely in the memoir category. It begins with the author’s first day at the fledgling network in 1979 (where he literally worked in the mailroom), then takes us through the development of all phases of the business over the next 35 years, ending with his retirement as cochairman of Disney Media Networks. Refreshingly, Bodenheimer doesn’t presume to be an authority on leadership; he never succumbs to telling others how they ought to lead. Instead, he simply and clearly describes what he and his colleagues did over the years, the good, bad, and — hey, ESPN is in the entertainment business! — even the silly of leadership. Because every action Bodenheimer takes, and every decision he makes, is in the context of leading ESPN, readers can see clearly — and assess for themselves — the practical value and validity of what he describes.

No one can predict with certainty the outcome of the torrent of fresh automation that’s upon us. But this is no faddish debate. As Martin Ford makes clear in his impressively researched and, yes, frightening Rise of the Robots, our choice for 2015’s best book on disruption, the evidence is ample that artificial intelligence is already occupying jobs previously thought doable only by humans. Robots are a death warrant for any job whose core requirement is experience or judgment. Lawyers, journalists, Wall Street analysts? Vaporized. Evaporated. Disappeared. The same goes for pharmacists, radiologists, even computer programmers. Most analysts believe that technological breakthroughs, although they destroy some jobs, end up creating far more by creating new industries and platforms. Ford flatly calls the theory outdated. Although we don’t think of white-collar work this way, many professions are reducible to small, repeatable components. And that makes them vulnerable to obsolescence. It gets worse. It’s a myth, Ford writes, that computers can perform only as they are programmed.

Captivology deals with the most fundamental struggle in marketing: how to get noticed. Author Ben Parr delves into studies from a range of disciplines over the last century that reveal the mysteries of human nature, using real-world examples. Steve Jobs garners praise for championing simplicity. But Parr also ropes in less obvious cultural signposts, such as actress Vivien Leigh, cookbook author Betty Crocker, and ex-congressman Anthony Weiner. According to Captivology, our choice for this year’s best book on marketing, why people do things is as important as what they actually do — and that’s a timeless insight. At root, Captivology brings the technology-addled marketing mind back to the basics of figuring out what makes people tick.

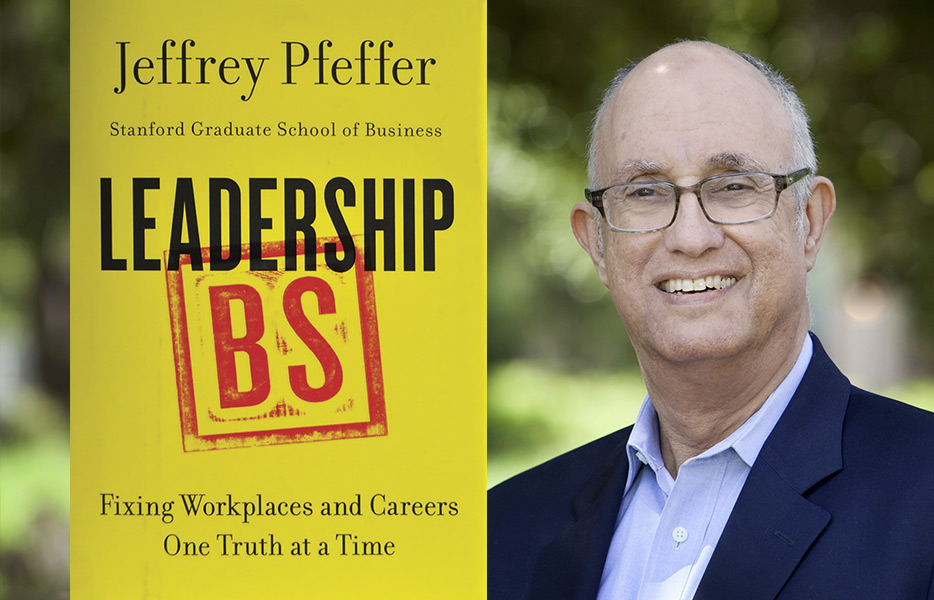

In Leadership BS, our choice for the best business book of 2015 on managerial self-improvement, Stanford Business School professor Jeffrey Pfeffer proclaims the industry of which he is a stalwart member to be a failure by the only measure that really matters: how often it makes good on its promise to produce more effective leaders. Pfeffer demolishes some of the industry’s most popular ideas and shows managers seeking self-improvement how to winnow out content that won’t help them or their employees. The idea of the authentic leader — and the books, seminars, and training programs that have sprung up around it — sets off Pfeffer’s BS detector. “The idea that one would or could be trained to become or at least appear authentic oozes with delicious irony,” he writes.

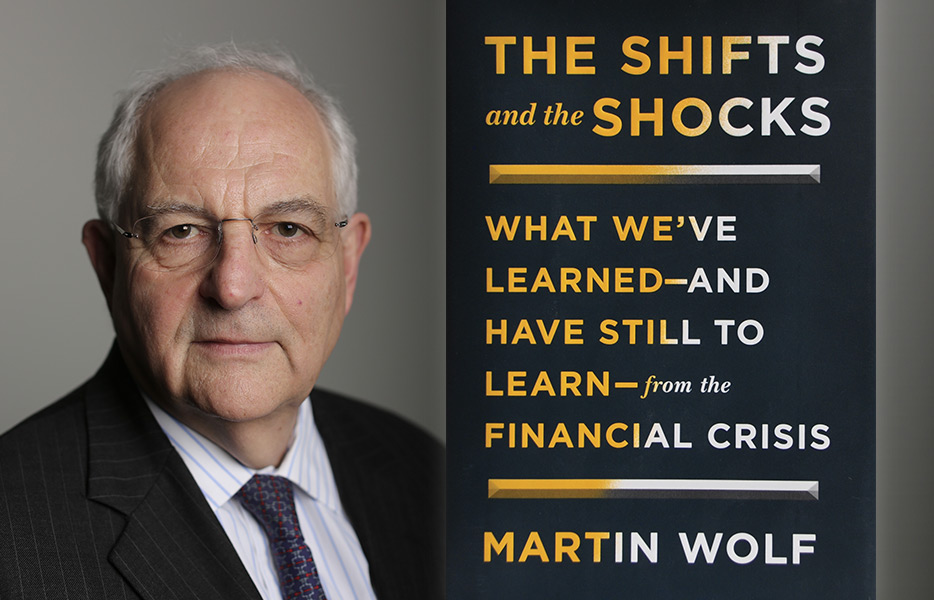

As the chief economics commentator of the Financial Times, Martin Wolf, who is British and based in London, holds no particular brief for political parties, on either the right or the left. Wolf’s general view is that President Obama and his counterparts in other wealthy countries were far too timid in confronting the crisis and its lingering effects. In The Shifts and the Shocks, our choice for the year’s best book on economics, Wolf brings a clarity to the discussion of economic issues that has been sorely lacking in the United States. “It now looks as though crisis-hit economies might never regain pre-crisis trend levels of output or even their pre-crisis rates of economic growth,” Wolf warns. The ruling orthodoxy everywhere has called for fiscal rectitude, and governments are striving to bring their budget deficits under control. This, Wolf argues, is likely to bring about “an enduring slump in high-income countries.”

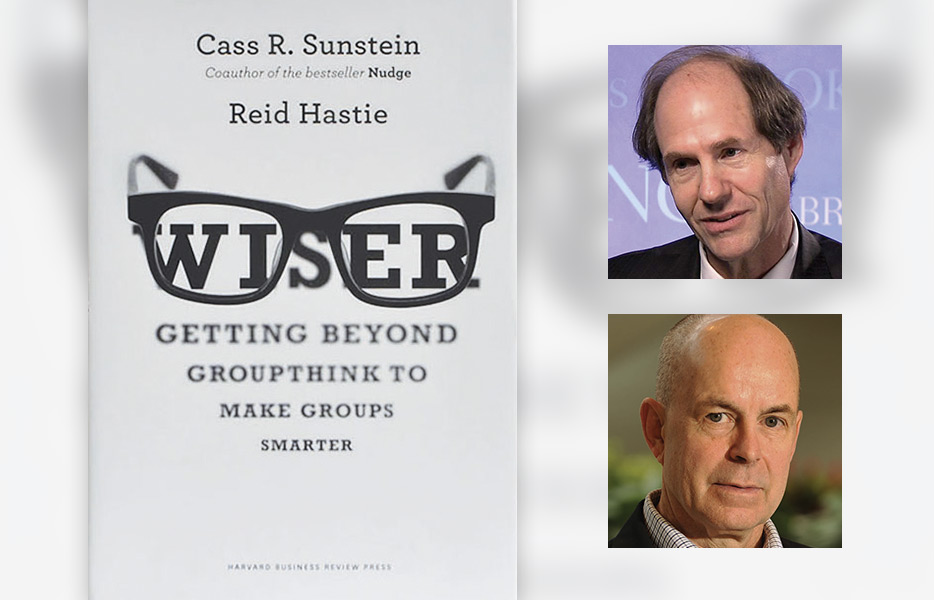

In Wiser, a representative of the ever-expanding literature of behavioral economics, Cass R. Sunstein and Reid Hastie mine personal experience, history, and social science for illuminating insights on how to do things better in groups. Wiser starts from the premise that groups of all sizes face significant structural barriers. Why? Because when humans get together, they fall prey to “groupthink.” They censor themselves and one another, defer too much to the opinions of leaders, and tend to adopt the view of the group’s most extreme members. What’s more, they are ill equipped to absorb and make use of new information. These patterns are toxic to innovation. After all, great innovation generally requires inspiration from unexpected places. In Wiser, our choice for best business book on strategy, Sunstein and Hastie don’t simply lay out the barriers to effective groups. They also prescribe effective means of overcoming them.