Disruptors and the Disrupted: A Tale of Eight Companies — in Pictures

The fear of disruption is often exaggerated. In reality, organizations that are threatened by new technologies and new players usually have more time than they realize to craft an effective response. For further insights, read “The Fear of Disruption Can Be More Damaging than Actual Disruption.”

Disruption is not new. More than 100 years ago, the Ford Motor Company made the automobile available to many, which revolutionized transportation — and disrupted a number of industries, including wagon and carriage businesses, and the makers of buggy whips.

Disruption is a perennial concern for business leaders, who worry that upstart rivals are on the verge of disrupting their business models and unsettling their industry’s equilibrium. The fear of making the wrong choices leads some companies to strategic paralysis. One example is the Polaroid Corporation: A pioneer in digital imaging in the 1960s, the company did not make the necessary investments to hold that lead in the 1990s, when digital photography overtook film.

Yet the fear of disruption is exaggerated. Although no one can predict exactly how much disruption will take place during the next five years, a recent study by Strategy&, PwC’s global strategy consulting business, found that companies facing disruption generally have longer to respond than they expect, and an effective response is typically available to them. Consider the decade or more it has taken for Amazon to meaningfully disrupt traditional retail.

The industries that suffer most from disruption are those whose players have no real differentiation — or, worse, are disadvantaged. Ride-sharing companies found it easy to disrupt the taxi industry because GPS systems and smartphone technologies had eroded the competitive edge that the navigational savvy of taxi drivers used to hold.

In other sectors, however, the appearance of new, disruptive players has actually helped the industry. The rise of brokered online vacation rental marketplaces has increased travel among all demographic groups. There are times when new and old models can coexist.

In fact, the success of online vacation rental marketplaces motivated some hotel chains, such as Marriott and Starwood, to raise their own competitive game, thus expanding their business-customer base. Indeed, when Marriott and Starwood merged in 2016 to become the world’s largest hotel chain, one of the most-noted aspects of the deal was the combination of their customer loyalty rewards programs, which brought together the best features from both to attract and hold more customers.

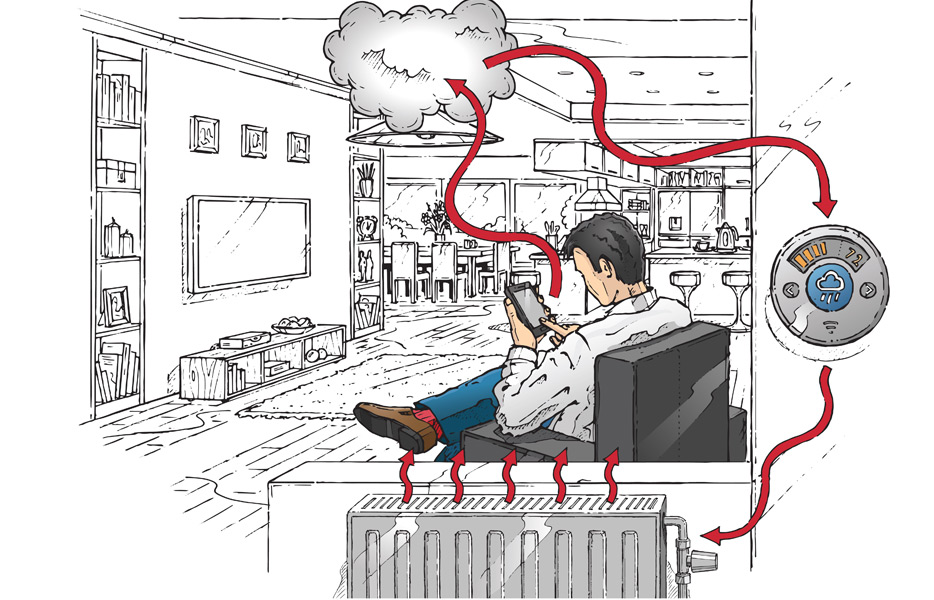

When facing new competition from Nest Labs’ smart-home thermostat, Honeywell also doubled down on its unique advantage: its embedded base of relationships with distributors, large-scale contractors, and other leaders in the industrials, building, and heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC) industries. No matter how many Nest thermostats consumers wanted to buy, their electricians and HVAC professionals were more familiar with Honeywell. This advantage gave Honeywell time to shore up its weaknesses in software user interface and product development so that its products could compete effectively against the Nest devices.

Doubling down on your distinctive strengths not only helps you fight disruption from upstarts, but it also enables you to disrupt an industry on your own terms. That’s exactly what Netflix did. In the late 1990s, the company competed directly with the Blockbuster retail chain. In 2007, when streaming video became viable, Netflix rapidly pivoted to offer that service. It began creating programming of its own a few years later, and it has pioneered the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to tailor its output to consumer interests. All along, its success has been enabled by a core distinctive strength: the ability to understand what its customers want and do, using in-depth analytics and the behavioral data it captures.

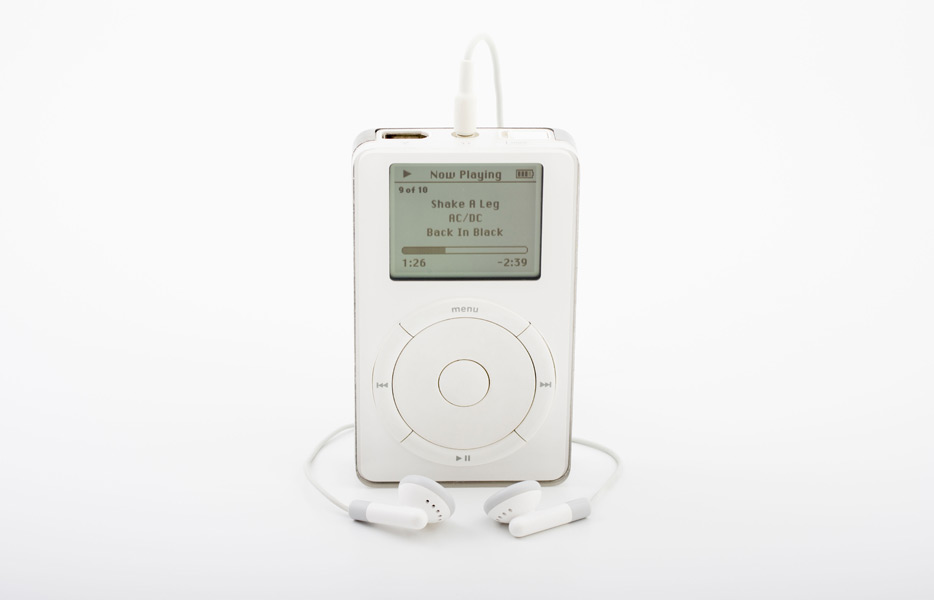

And if you don't have those great capabilities yet? It's not too late to start building them. Results will appear long before they’re fully built. And there is no greater defense against disruption than having capabilities that will outlast nearly all market changes. Apple proved this when it began developing its digital hub strategy in the late 1990s. By 2001, six years before the launch of the iPhone, it had already introduced an MP3 music player, a digital video camera, and its groundbreaking iTunes store. Companies have the time to build something great — they just need to commit to it.