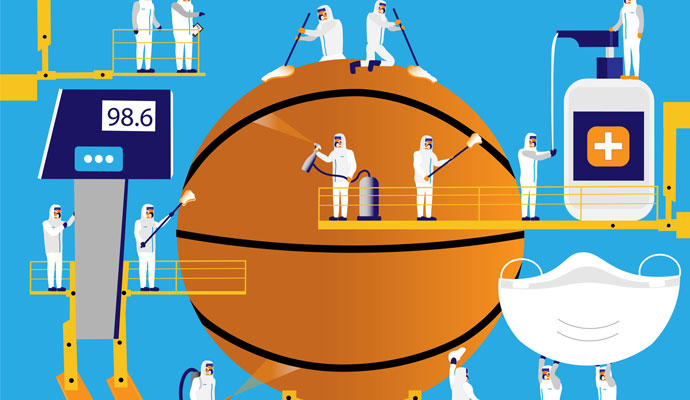

How the National Basketball Association Put the Bounce in Basketball

Once a purely American sport, basketball has been transformed by the N.B.A. into a global phenomenon. What marketing lessons does the N.B.A. teach? If you promote it, the fans will come.

In a crowded commercial world, where marketers fight for each moment of each consumer's time, the competition is first for "share of mind" and only then for market share. Nothing illustrates this battle for the consumer's attention span better than the jousting for fan support that is central to professional sports.

In the United States, where baseball, football, hockey, golf and tennis are all backed by powerful marketing machines, the National Basketball Association has created an unsurpassed model for building brand equity. That model is even performing strongly beyond America's borders, where basketball is making a serious run at soccer, the most global of sports in terms of fan popularity and participation.

Since taking over as commissioner of the N.B.A. a little more than a decade ago, David J. Stern has transformed a collection of flagging franchises into a well-oiled money machine that flexes its muscles both on and off the court. In the process, the N.B.A. has become a case study for any organization struggling to break out of the pack, offering lessons in how to establish a brand name and then extend it in directions both obvious and innovative.

Last year, the N.B.A. took in $1.2 billion from ticket sales and television rights, more than four times the $255 million of a decade ago. But that is only for openers. The really big dollars now come from innumerable ancillary products and promotional tie-ins, the growing offspring of a network of licensing arrangements and sponsorships with more than 150 companies, including such giants as Coca-Cola, McDonald's and Nike. These relationships, many of which are long term in nature, brought in more than $3 billion in 1996, a thirtyfold increase from the $107 million of 10 years ago.

This combined $4 billion-plus revenue stream isn't a bad haul for a basic labor force that numbers just 348, the sum of the 12-man rosters of the league's 29 teams. And it shows no signs of leveling off. Even though basketball is something of a mature business -- its arenas are filled to 92 percent capacity for the average game -- its earnings potential is limited only by the size of the world market itself. With offices in 8 foreign cities and television broadcasts in some 180 countries, the N.B.A. has already become one of America's biggest exporters, ringing up 16 percent of its $3 billion in product sales abroad. The league is now making a full-court press to raise that foreign contribution to fully a third of product sales within a decade.

It is not a far-fetched goal. The N.B.A., no less than Coca-Cola, McDonald's and Nike, has carefully built and nurtured a deeply emotional bond between its product and its customers, a bond that transcends the game itself. The N.B.A. logo triggers a marketer's dream response: respect, excitement, quality, dynamism and fun. It is a club people want to join, a community in which to participate. The sight of 12-year-old boys on the streets of Paris and Mexico City wearing Chicago Bulls jerseys no longer raises eyebrows. The stunning rise of the N.B.A.'s popularity in countries like Japan, which has virtually no basketball tradition or fan base, is testament to the league's marketing savvy.

Mr. Stern has turned his commercial hoop dreams into reality with the kind of razzle-dazzle play that is the hallmark of the teams he oversees. In his case, he has combined the driving skills of a hardball labor and contract negotiator with the deft moves of a master salesman. Above all, along with the team he assembled in the commissioner's office, he has stuck to a solid game plan while remaining open to the sudden unexpected opportunity.

"Stern and his colleagues had terrific vision," said Stephen A. Greyser, a professor of consumer marketing at the Harvard Business School who teaches a course about the business of sports. The N.B.A., he said, became focused on brand equity in the early 1980's when no other sports leagues and very few companies even understood the concept.

It nurtured that brand by tightly controlling how its licensees presented its image and message. It imposed the same sort of quality assurance on its 29 sub-brands, the individual teams, through a strong -- yet supportive -- central administration. And it kept the peace on its "factory" floors and in its front-office suites by pioneering salary and revenue-sharing arrangements that made players and management rich together without having to endure painful work stoppages, something that has eluded a number of other sports, notably baseball.

All this has paid off with the kind of synergies that management books often talk about but that are all too rarely seen in the real world. Not only has the N.B.A. prospered, but so have the companies, like Nike, that have become so closely identified with the sport. And some of the league's players are now household names throughout the world, not just in the United States, making them commercial gold mines for themselves and the league. A small but growing number have attained the level of celebrity status usually reserved for movie and rock stars. Indeed, Michael Jordan, Shaquille O'Neal, Dennis Rodman and several others have become movie stars.

To be sure, there have been misplays along the way. Early on, Mr. Stern underestimated the value of Mr. Jordan's pact with Nike, perhaps the single most important commercial alliance in sports history. And this year, the N.B.A.'s television ratings in the United States are sagging, albeit along with those of most other professional sports.

None of which takes anything away from Mr. Stern's playbook, whose moves travel easily from the backboard to the boardroom.

Professor Greyser ticked off some of the winning plays, applicable to general consumer industries no less than sports leagues:

![]() Develop line extensions for the brand. The N.B.A. has done that numerous times over the years. Its newest extension is the W.N.B.A., a professional women's league that will compete in eight cities starting in 1997.

Develop line extensions for the brand. The N.B.A. has done that numerous times over the years. Its newest extension is the W.N.B.A., a professional women's league that will compete in eight cities starting in 1997.

![]() Forge strategic alliances. The league has been extremely skilled at alliance building, not only with retailers but with critically important television networks.

Forge strategic alliances. The league has been extremely skilled at alliance building, not only with retailers but with critically important television networks.

![]() Gain visibility using other people's money. In its symbiotic relationships with the networks and with corporate sponsors like Nike, the N.B.A. has garnered endless advertising and marketing goodwill without spending any of its own money. And the league has taken a much-rewarded long view in its alliances by "not grabbing for every last dollar," Professor Greyser said. "The N.B.A. realizes that having your partners participate in the upside is a positive thing."

Gain visibility using other people's money. In its symbiotic relationships with the networks and with corporate sponsors like Nike, the N.B.A. has garnered endless advertising and marketing goodwill without spending any of its own money. And the league has taken a much-rewarded long view in its alliances by "not grabbing for every last dollar," Professor Greyser said. "The N.B.A. realizes that having your partners participate in the upside is a positive thing."

![]() Find ways to stay in the limelight. The N.B.A. has had an uncanny knack for creating attention-getting events, like the Olympic Dream Team. The league also sponsors off-the-court community programs, like Stay in School and Fan Fest, which pay off in marketing presence as well as in goodwill.

Find ways to stay in the limelight. The N.B.A. has had an uncanny knack for creating attention-getting events, like the Olympic Dream Team. The league also sponsors off-the-court community programs, like Stay in School and Fan Fest, which pay off in marketing presence as well as in goodwill.

Mr. Stern executes these moves with the help of a large team of pumped-up assistants.

He has built a front-office staff, now 600 strong, in his own hard-charging image, said Edward Levin, a principal at Booz-Allen & Hamilton who recently completed a benchmark study of branding practices and looked closely at the N.B.A. Like the employees at other non-traditional marketers, including Iam's Pet Food and Snap-On Tools, those who work for the N.B.A. are highly motivated and widely empowered.

"Stern built an organization that cared passionately about the game and the brand," Mr. Levin said. "They bring a missionary fire and zeal because they really believe in it." Talk to N.B.A. employees and they market the product, whether they are in operations, finance, human resources or sales.

Professor Greyser added that the league has begun hiring M.B.A.'s in the last two or three years, specifically to help manage the brand internationally.

And like other great brands, the N.B.A. acknowledges its weaknesses and constantly updates its product by tweaking the rules and adopting new ideas. In its early years, when the league suffered from a dreadfully slow-paced game, a 24-second shot clock was introduced. Since then, the league has introduced the three-point shot, shorter timeouts and tougher officiating to curb violence in the game.

"Other than the 10-foot basket, very little is untouchable," said Bill Daugherty, the N.B.A.'s vice president for business development. "We're always able to keep the sport contemporary."

Mr. Stern gets the lion's share of the credit for all this.

Mr. Stern gets the lion's share of the credit for all this.

"David Stern is certainly the best brand manager in sports and I'd compare him to any of the great brand managers anywhere," said David Green, senior vice president for international marketing at McDonald's.

A lawyer by training and the N.B.A.'s vice president for business operations for three years prior to becoming commissioner, Mr. Stern was responsible for creating NBA Properties, the league's licensing division. A voracious reader, Mr. Stern has a penchant for poring over trade journals from the entertainment and broadcast industries to learn the intricacies and trends of those businesses.

"He's as likely to hand me a clip from Variety as from The New York Times," said Rick Welts, the league's executive vice president and chief marketing officer.

In the early years, Mr. Stern used organizations like Disney and McDonald's as his marketing role models, rather than Major League Baseball or the N.F.L. He coupled his feel for the product with an unparalleled sense of the importance of television and sponsor relationships. Accordingly, he built the N.B.A. as an entertainment conglomerate, extending the brand through dozens of licensed products much as Disney does with toy makers and clothing manufacturers.

Mr. Levin, of Booz-Allen, credited Mr. Stern with seeing the need to "transcend" the product. "By choice and by design, David Stern started looking at the N.B.A. as a brand rather than as a loose association of clubs," Mr. Levin said. "He also recognized the emergence of the players as three-dimensional personalities who would become much more than basketball players."

Indeed, though professional athletes had long been heroes and role models, Mr. Stern made a clear and intentional effort to raise N.B.A. stars beyond that level and turn them into entertainers and celebrities.

Despite the often idiosyncratic nature of athletes, Mr. Stern embraced the personality-driven aspect of the game. All the league's promotional campaigns highlight its stars and the unabashed enthusiasm of the fans at courtside. The N.B.A., with a long tradition of star players like Wilt Chamberlain and Elgin Baylor, had done little to build them into national media figures the way Mr. Stern did for the players of his era.

For if he understood anything, it was the power and might of television. Mr. Stern's tenure began just as cable television experienced its first burst of popularity. He recognized the telegenic beauty of basketball, a sport seemingly invented with television in mind, and knew immediately that he had to exploit that quality via such new delivery outlets as the Turner Broadcasting System's TBS and TNT channels.

He forged agreements with both the commercial and cable networks, building a focus on the entertainment value of the N.B.A. and creating a ubiquitous electronic stage for the league and its cast of young superstars. In an unprecedented partnership, not only are N.B.A. games shown on both NBC and Turner Broadcasting, but each network actively promotes the other on the air.

"Where else can you see someone like Bob Costas on NBC tell his viewers to watch TNT on Tuesday night instead of his own network?" said Peter Land, director of marketing communications for the N.B.A.

And because the N.B.A. is highly protective of its brand, it insists on having an active role in the broadcasting of its product, Mr. Land pointed out. More than a dozen N.B.A. executives participate in weekly meetings with the networks, providing input on everything from players to be featured on NBC's weekly "Inside Stuff" program to new camera angles for games. The mandate is clear: showcase the product!

"There are 20 million admissions to N.B.A. games each year but that represents maybe 5 million different people," said Mr. Welts, the chief marketing officer. "That means that 95 percent of our fans experience the N.B.A. on television."

Individual N.B.A. teams broadcast more than 1,100 games each season but only 120 are aired on national network or cable television, which can be seen abroad via satellite. Nearly 90 percent of the league's games are therefore available to be repackaged and broadcast around the world.

The N.B.A. also benefited handsomely from two serendipitous but synergistic trends. The remarkable rise in popularity of college basketball and the NCAA Final Four championships put emerging young stars like Shaquille O'Neal, Grant Hill and Anfernee Hardaway on national television dozens of times before they entered the N.B.A. They were already celebrities when they arrived. And with aggressive sponsors like Nike and Reebok using innovative advertising campaigns to turn N.B.A. stars into international sensations, the league reaped vast residual benefit at no cost. (Other sports have benefited in this way, too, of course, but not to the same degree. The sponsors in those games tend not to be as heavily dependent for their business on sports advertising. Nike, by contrast, fuels almost all of its growth and profits from basketball shoes.)

Mr. Stern also established a powerful and intricate organizational structure -- in some respects centralized, in others highly decentralized -- that was designed to promote and protect the brand.

While the league is a confederation of 29 independently owned franchises, each with its own marketing organization, the N.B.A. provides a unifying and stabilizing influence not seen in other professional sports. When the Minnesota Timberwolves' ownership experienced financial hardship a few years ago and proposed to move the franchise, for example, the N.B.A. office sent dozens of its top managers to Minneapolis for months to work out a sale of the franchise to local investors and keep the team where it was.

In return for all the support, the teams stay in lockstep with the league's marketing and branding philosophies in order to fuel a massive revenue-generating machine that benefits everyone. (See box on facing page.)

"Part of the reason they have such control is that the teams have given it to them," said Mr. Levin of Booz-Allen. "Mr. Stern had some early wins and rallied the owners around him." Unlike their counterparts in professional baseball and football, the N.B.A. owners have all bought into Mr. Stern's dictum to let the game and the players shine while they and their egos remain in the background.

Because its chief assets wear sneakers and are subject to injuries, retirement, unusual behavior and other human frailties, the N.B.A. has had to build a deep and broad foundation for its product to survive and prosper.

For that reason, Mr. Stern is not afraid to take the league into businesses that stray from its core competency if it will enhance the brand. In 1988, for example, not a single trading card company offered basketball cards. Mr. Stern believed that a key way to build brand loyalty among the youngest fans was to have them trading basketball cards the same way they traded baseball cards. So he took the N.B.A. into the trading card business, creating a joint venture with a distribution company. The league took the photos, produced the cards and swallowed the investment costs. "We were willing to make the investment because of the benefit from a branding standpoint," said Mr. Daugherty, the vice president for business development. Today, the league has licensing agreements with four major trading card makers: Topps, Fleer, Skybox and Upper Deck.

As with its television operations, the N.B.A. retains tight control over every aspect of its marketing, Mr. Levin of Booz-Allen pointed out, including veto power with even its most powerful sponsors, like Coca-Cola, McDonald's and Nike. A sponsor, for example, must demonstrate "aggressive" support of the N.B.A. brand or the relationship will be terminated. The league recently parted company with a major cereal manufacturer because it simply wasn't demonstrating enough enthusiasm in its advertising for the N.B.A. relationship. Such influence came slowly, with careful orchestration.

And as the league's arenas began to sell out regularly in the 1980's, Mr. Stern knew he had to extend the brand in ways other than ticket sales. "He understands that he can't do it alone," said Mr. Green, the senior vice president for international marketing at McDonald's. "He's made sure he has alliances and relationships with other companies and countries to insure a robust spread of the brand."

The N.B.A. approached McDonald's, for example, in the late 1980's after the league saw how effectively the fast-food chain had promoted Mr. Jordan. McDonald's agreed to sponsor an international tournament featuring an N.B.A. team in a European venue. Mr. Green said he was impressed by the fact that the N.B.A.'s representatives were not focused on finances or media plans but on how the two organizations could work together to extend both brands.

"They saw us as an interface with 23 million people who go through our restaurants each day around the world," Mr. Green said. "And we saw a global relationship as well as a domestic one."

Though McDonald's does promotions with other professional sports leagues, the relationship with the N.B.A. is the strongest and longest lasting, Mr. Green noted.

Over the years, the two organizations have collaborated on numerous promotions, including the McDonald's Championship in Europe and a basketball skills program called the McDonald's N.B.A. 2ball. This year, McDonald's became the N.B.A.'s outlet for distributing All-Star ballots, handing out no less than 50 million of them, which generated the largest voter response by far in league history.

Beyond that, the long-term nature of the relationship "lets us break some rules, take some risks, to extend the brand," Mr. Green said. McDonald's will be part of the promotion for the new women's league, for example. "The great thing about long-term partnerships," he said, "is you are more apt to take a risk because you know you have the same long-term goals. And it keeps you interested."

What ultimately makes the relationship work, he said, is that the N.B.A. has a very clear brand image with McDonald's customers, an image focused on personalities and values that have their approval.

Of course, all this was not readily apparent when Mr. Stern took over in 1984 and inherited a "sleepy brand," according to Mr. Green, along with a well-documented set of problems. In the late 1970's, the N.B.A.'s image had become tarnished from a league-wide drug problem. There were also labor disputes. The result was sagging attendance and demoralized franchises. The game that had been touted as "the sport of the 1970's" was staggering.

As player salaries soared out of control, the N.B.A. reached a crossroads and Mr. Stern, who had also served as the league's general counsel, demonstrated his skills as a negotiator. He brokered a key agreement with the players and owners to institute a "salary cap," which set limits on a team's payroll. At the same time, he broke new ground by getting the owners to sign a collective-bargaining agreement that featured revenue sharing with the players. It was the basis for a win-win relationship that was unprecedented in sports. A league that was spiraling toward financial insolvency was suddenly stabilized for the long term. Included in the financial agreements were strongly worded drug policies that helped eliminate that problem as well.

Along with all the negatives, Mr. Stern inherited two young superstars, Magic Johnson of the Los Angeles Lakers and Larry Bird of the Boston Celtics, who had joined the league together in 1979 and began a decade-long, cross-country rivalry that would rivet the sports world through the 80's.

The new excitement came just at the right time to capitalize on the explosive growth of cable television. The television set had truly become a global electronic fireplace and basketball broadcast remarkably well: fast, nonstop action, with highly recognizable players -- not hidden by helmets, caps or padding -- showing off their skills in an esthetically pleasing game.

In the fall of 1984, the most photogenic athlete of his generation, a rookie named Michael Jordan, arrived in Chicago, and his presence eventually raised the visibility of the N.B.A. to levels that astounded even Mr. Stern.

For many, the multitalented, multidimensional Mr. Jordan has come to symbolize the N.B.A. brand and its best attributes. His fluid, ballet-like athleticism coupled with his polished good looks and impeccable flair has elevated Mr. Jordan far beyond basketball itself. He may well be the most recognizable celebrity on the planet. And much of this rise to mythic hero status was driven by Nike and its groundbreaking marketing campaigns built around him.

The simultaneous rise of the N.B.A., Nike and Mr. Jordan was not coincidental. Each fed off the customer value of the others and, like Mr. Jordan soaring for a slam-dunk, they drove the visibility of each entity higher and higher. Few recall that Nike was a struggling brand when it signed Mr. Jordan. The company was in the red for two straight years and laid off 400 workers prior to Mr. Jordan's rise to prominence. But by 1996, Nike was the dominant manufacturer in its business, with 44 percent of the athletic shoe market in the United States and $3.6 billion in sales.

The confluence of star, product and television made it clear to Mr. Stern and his fellow executives that the lure of the N.B.A.'s brand was personality driven. This was not always obvious, even to Mr. Stern.

The confluence of star, product and television made it clear to Mr. Stern and his fellow executives that the lure of the N.B.A.'s brand was personality driven. This was not always obvious, even to Mr. Stern.

In fact, one of his first high-profile actions as commissioner was to impose a $1,000 fine on Mr. Jordan for wearing his first pair of Nike Air Jordan sneakers, in the opening game of the 1984-85 season. The controversial red-and-black sneakers were unacceptable under strict league guidelines for player apparel. Mr. Jordan and Nike then got together with the league to agree on less radical looking sneakers. But the N.B.A. ban on the original pair touched off a huge furor that Nike quickly milked to perfection. In the wake of Mr. Stern's decision, basketball fans across the country rushed out to buy Air Jordans. Nike sold $100 million worth of the shoes in the first year alone and Mr. Jordan's celebrity was minted in the process.

And if a sense of community drives great product successes, the community that has built up around Mr. Jordan has provided residual benefit to the N.B.A. brand. When Mr. Jordan retired from the N.B.A. for 18 months to try his hand at baseball, the league didn't miss a beat. Mr. Jordan continued as a highly visible spokesman for Nike throughout his hiatus. The marketing campaigns for the league, the television networks, the players and the products tend to blur together for the average fan, leaving a positive net effect on all parties.

The N.B.A. also gets a positive spillover from college basketball. The NCAA Final Four, one of the top televised sporting events each year, is a showcase for future N.B.A. stars, and this smooth flow from one venue to the next has made even the N.B.A. draft a nationally televised event viewed by millions.

And a decision in 1989 by FIBA, the international basketball governing body, to allow professional athletes to compete in the Olympics also proved a boost to the N.B.A. In 1992, the original Dream Team came together in Bar-celona to represent the United States. The American team, which once featured top college talents, now boasted the likes of Mr. Jordan, Mr. Bird, Mr. Johnson, Charles Barkley, Scottie Pippen and other top professionals.

The sight of these stars on one court competing for the United States had a dramatic impact on the global game, so much so that it caught everyone by surprise, including Mr. Jordan. It was as if the Beatles had reunited for a tour. "I don't think anyone knew what to expect," Mr. Jordan said. "This was the first time this had happened. But as we started traveling around and seeing helicopters and motorcades all over the place, we realized, 'Hey, this is really big.' "

Added Magic Johnson, "The Dream Team made basketball the game it is around the world."

But actually, Mr. Stern deserves credit here as well because he had been busy laying much of the groundwork.

Under his leadership, the N.B.A. was an early adopter of the "Think Global, Act Local" approach to marketing and it set up league offices in Geneva, Hong Kong, London, Melbourne, Mexico City, Miami (for Latin America), Paris, Tokyo and Toronto. More than 70 full-time N.B.A. staffers are stationed in these cities, giving the N.B.A. more overseas personnel than all other American professional sports leagues combined. And there are plans to add another 150 people over the next three years.

"With these people on the ground for the N.B.A., we have a better record of television placement, media placement, consumer products with retailers and just a much greater overall presence," said Mr. Daugherty, the vice president for business development. "It is a key to the globalization of the sport."

Professor Greyser of Harvard gives high marks to the Stern team for having that global vision and finding ways to implement it. "Twelve years ago, the idea that basketball would become the second most popular sport in the world, and No. 1 in some cases, was not that clear," he said. "Now, if you walk down a street anywhere and say 'Michael' or 'Shaq,' they know who you are talking about."

Indeed, in many places outside the United States, the N.B.A. now evokes a nearly religious fanaticism that was once reserved for soccer. Though purists rightly attribute much of this appeal to the star players, the spread of the N.B.A. had as much to do with Big Macs and Cokes. The N.B.A. preached its gospel relentlessly in Europe, South America and Asia through television broadcasts, local promotions, participatory basketball programs and tournaments and sales of licensed products. Over the last two years, for example, 10 of McDonald's top markets around the world have had N.B.A.-related promotions. In Greece, the local McDonald's ran videos of N.B.A. bloopers on Sunday afternoons and basketball fans jammed the restaurants.

As it chases soccer for sports supremacy, basketball has something soccer does not: a single league in which the best players in the world compete. As more and more foreign-born stars emerge from Europe, Africa, Australia and eventually China to play in the United States, the N.B.A. will further epitomize a transnational corporation whose products cross all geographic boundaries. These international stars, like new model cars or hit movies, keep the game at the forefront, which is a basic strategy of the league. Accordingly, the league goes to great lengths to promote these stars in their local markets.

As much as things are going well these days for the N.B.A., there is still a litany of problems facing league executives: too many low-scoring games, young players skipping college to rush into the N.B.A., injuries to marquee players like Mr. O'Neal, the erratic behavior of a player like Chicago's Mr. Rodman and the inevitable retirement of Mr. Jordan.

The all-too-human nature of the N.B.A.'s product creates "an incredibly insecure" environment, Mr. Daugherty said, and like Intel or Cisco Systems, the league takes nothing for granted. "We operate with the philosophy that it is all going to fall apart tomorrow," he added.

But he also pointed out that the N.B.A. had weathered countless crises that doomsayers predicted would cause its demise.

"There will always be issues in a sports league," Mr. Daugherty said. "The fact that people around the world care and we make headlines over these things is the best news of all."

Rules of the GameUnder David J. Stern, the National Basketball Association has built a business model that fully developed and extended its brand. Here are some of the N.B.A.'s successful branding methods:

Dominate the Boards -- As the mothership for its fleet of 29 franchises, the N.B.A. retains tremendous control. The league negotiates and oversees all national and international television rights, sponsorships and license relationships, with revenues shared equally among the teams. This sharing has created unprecedented stability for N.B.A. franchises, allowing teams in smaller markets to remain competitive with those in major ones. It has also promoted strong fan bases. As a result, no N.B.A. franchise has relocated in nearly 15 years.

Take it to the Hoop -- The N.B.A. has tracked the growing popularity of basketball around the world and has pushed its brand relentlessly through joint efforts with sponsors like McDonald's. In addition to maintaining a network of offices overseas, the league co-sponsors events like the McDonald's Championship (in Paris in 1997) that feature top teams from around the world. The league now includes two franchises in Canada and serious discussions are under way to put a team in Mexico City. Though it has no intention of adding franchises in Europe and Asia, the league is committed to sending N.B.A. teams to play in foreign cities like Tokyo and Paris in order to give the brand the fullest exposure.

Long-Range Jumper -- The N.B.A. has itself become a multinational product, with a growing number of foreign-born players, like Nigeria's Hakeem Olajuwon and Germany's Detlef Schrempf, on the rosters of nearly every team. The N.B.A. recognized the powerful impact the 1992 U.S. Olympic team, known as the Dream Team, had on the sport globally. The league's goal is to quickly raise international competition, like the Olympics, to such a level that three or four nations will send teams composed entirely of N.B.A. players.

Fill the Lane -- The N.B.A. is the most widely distributed television sports property in the world, providing its games to broadcast outlets in 180 countries. The NHK network in Japan, for example, airs three games a week. "We get better media coverage in Japan than we do in a lot of N.B.A. cities," said Terry Lyons, the league's vice president for international public relations.

Playing Above the Rim --The league has set stringent quality standards for both its sponsors and its licensees and is relentless in insisting that the N.B.A. brand be promoted in the most favorable light. The N.B.A. requires that sponsors, for example, have extensive network advertising campaigns on NBC and Turner Broadcasting, where its games are shown in the United States, along with national retail support.

In the Zone -- Each franchise negotiates local television and radio rights and keeps those fees along with ticket revenues. But the franchises, while autonomous, work closely with the league office in marketing the product.

Off the Bench -- The N.B.A. has a team services department, which serves as a hub and funnels entertainment packages and information about community activities, local retail promotions and arena guidelines among the franchises. "The league sends us two thick volumes twice a year with every service, every activity, every promotion available for us to use," said Stuart Layne, executive vice president for marketing and sales at the Boston Celtics. Mr. Layne, who worked in marketing in baseball, said no other sport has such franchise support.

Home Court Advantage -- The league masterminded an effort to get all of the teams into new or refurbished arenas over the past 15 years and provides blueprint support for a franchise when a new arena is being constructed. It offers guidelines about pricing everything from luxury boxes to courtside sign-age. Because most games are sellouts, ticket sales are not a vehicle for growth. So the N.B.A. has encouraged local owners to view the franchise as the centerpiece of a multidimensional entertainment outlet in order to keep their arenas operating 250 to 300 days and nights each year. In that vein, many franchises also own teams in such other sports as indoor soccer or arena football.

Show Time -- In June 1997, the N.B.A. extended the brand further by launching the W.N.B.A., a professional women's league, which will play during the summer, while the men are off. The N.B.A. also has a popular Website on the Internet -- www.NBA.com -- which has recorded more than 4 million hits a day, a third from abroad.

Full-Court Press -- Research has shown that if a child plays basketball at age 11, he or she is eight times more likely to be a fan at age 25. So the N.B.A. fosters participation with a series of grassroots events for youngsters in the United States and abroad, co-sponsored by Coca-Cola, McDonald's, Pepsi and others.

THE BOSTON CELTICS:A MARKETER'S CHALLENGE

In early May, Stuart Layne experienced the kind of overnight marketing turnaround brand managers only dream of.

As executive vice president of the Boston Celtics for marketing and sales since 1994, Mr. Layne has had the dubious task of selling a damaged product to a highly sophisticated and deeply cynical customer base. The Celtics, the N.B.A.'s most storied franchise, winner of 16 championships and a tradition-rich, internationally renowned brand, had stumbled badly.

Indeed, coming off the just-completed season, the Celtics were a marketing manager's nightmare. Since last winning a championship in 1986, the team saw its fortunes fall sharply, reaching rock bottom this year with a 15-67 record, its worst ever. Ticket sales had tumbled, fan interest was waning and the media had made the team a target for its wrath.

But in May, Celtics owner Paul Gaston persuaded Rick Pitino to leave the University of Kentucky and take over as the team's coach and president. Mr. Gaston reportedly agreed to pay Mr. Pitino $70 million over 10 years to lure him from Kentucky, an amount that made him the highest-paid coach in sports history.

Mr. Pitino was accorded a hero's welcome in Boston, where he had started his coaching career in 1978 at Boston University. He had achieved remarkable success at every stop in his career, most recently taking a Kentucky program in turmoil and rebuilding it into a national champion. His arrival brought more than a glimmer of hope for Celtics fans; it immediately rekindled the fire that had fueled local passion for the team for decades.

For Mr. Layne, Mr. Pitino could not have arrived at a better time. Ultimately, a marketer is only as good as the product he is selling, and Mr. Layne finally has the product to sell.

"He's the real deal," Mr. Layne says of Mr. Pitino. "Where we might have been focusing on marketing and how to position the team, now the focus is on the product. Our fans understand what he brings to the table. The N.B.A. model has been to sell the celebrity status of the players. We just got a tremendous celebrity."

According to Mr. Layne, ticket sales, sponsorship opportunities, broadcast relationships and the Fleet Center, the team's arena, will all benefit greatly. In just the first three days after Mr. Pitino signed his contract, the team sold 1,200 of the 3,000 season tickets it had available.

Brand managers at companies like Kodak or I.B.M. understand that Mr. Pitino's decision to join the Celtics was not the result of serendipity or the lure of huge financial rewards. In news conferences, Mr. Pitino repeatedly stressed his view that the team was one of the great sports franchises and that the challenge of returning the luster to the Celtics was his main reason for taking the job. It was much the same reason that caused George M.C. Fisher to go to Kodak and Louis V. Gerstner Jr. to switch to I.B.M. In all three cases, the transition to powerful new leadership occurred because these turnaround specialists believed in the essential strength of the brand.

"The lesson from this for other brand managers is that we never discounted our product," Mr. Layne said. "We never told people it was worth less than its real value. One of the great things about the Celtics brand was that it was able to attract a marquee talent like Pitino when others couldn't."

The brand had been built player by player, title by title. Like BMW or Porsche, the product earned respect by putting an unceasing premium on quality and high performance. The term "Celtics Pride" was coined to embody the brand and it spoke volumes.

The team had a patriarch in Arnold (Red) Auerbach, its highly successful coach and later general manager. He built teams that were marked by a blue-collar, no-frills work ethic that matched the character of the New England region and its deeply loyal, no-nonsense fans. Celtics fans were considered "hard core" -- sophisticated, knowledgeable basketball aficionados who not only appreciated their own team's success but applauded the efforts of competitors as well.

The team played in one of the league's oldest buildings, the Boston Garden, on a unique parquet floor. Visiting teams were usually intimidated simply by entering the arena.

Unlike most N.B.A. franchises, the Celtics eschewed glitz and glitter. Show time was for L.A. The Celtics had no cheerleaders, dancing girls or even a mascot. There were no rock songs or laser light shows in the Garden; the fans would have none of that. An old organ provided all the entertainment during timeouts and half time. In the late 1970's, the marketing department tried putting a young man dressed as a leprechaun on the floor to exhort the crowd. He was booed and heckled mercilessly and after one game was never seen again.

Like other troubled businesses, when the Celtics began to unravel in the late 1980's, the descent was swift. Larry Bird, perhaps the greatest Celtic player ever, struggled through debilitating injuries and then retired in 1992. Just a year later, the team's young star and captain, Reggie Lewis, died of a heart attack. The product suffered, both on the basketball court and in the court of public opinion.

For Mr. Layne, the task of rebuilding the brand prior to Mr. Pitino's arrival, therefore, was more than daunting. The situation in Boston "is very different from the rest of the league," he said. "We're still the only N.B.A. team without a dance team or cheerleaders. That is indicative of what our fan base believes the Celtics are about."

But as the Celtics struggle back to respectability on the court, the team can call on its hidden assets. Edward Levin, a principal at Booz-Allen & Hamilton, said the Celtics have retained "a latent equity" that most brands can only pine for.

"The Celtics have a tradition and brand equity that other teams don't have," said Mr. Levin, who recently completed a study of branding practices. "They have shown consistency; they've sent out the same message over time, which is critical in brand marketing."

Now the challenge is to "manage expectations,'' said Stephen A. Greyser, a professor of consumer marketing at the Harvard Business School. It is important, he said, to make sure that Celtics fans "don't assume the team will win 50 games next year."

Mr. Layne agreed that his job is to keep the excitement on a realistic level. "We laid the groundwork over the last couple of years in expanding our fan base, getting more people interested in basketball," Mr. Layne said, referring to the 1,000 tickets at $10 that the Celtics made available at all home games. "This expanded fan base will be turned on by this much better product." ![]()

Reprint No. 97307

| Authors

Glenn Rifkin, glennrifkin@worldnet.att.net Glenn Rifkin has covered technology for the New York Times and has written for the Harvard Business Review and Fast Company. He is coauthor of Radical Marketing (HarperBusiness, 1999) and The CEO Chronicles (Knowledge Exchange, 1999). |