Symantec’s Strategy-Based Transformation

How fresh leadership, serial acquisitions, and a new market made CEO John Thompson’s billion-dollar promise come true.

(originally published by Booz & Company)One of the sacrosanct rules for sustaining shareholder value is to underpromise and overdeliver. Never is this rule truer, nor are the consequences of delivering less than what’s promised worse, than in a corporate turnaround situation. So when the Symantec Corporation, a global software technology company based in Cupertino, Calif., put together a business plan committing to annual revenue growth of 20 percent and delivered something closer to a flat line, Wall Street’s punishment was swift and severe: 38 percent of the company’s value vanished in a day.

|

|

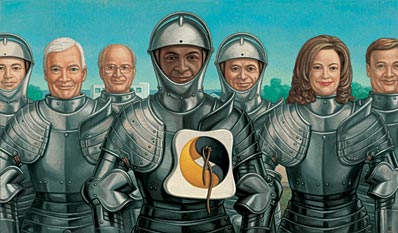

Illustration by Marco Ventura |

| Symantec’s Transformers: (left to right) Stephen Cullen, SVP, Consumer and Client Product Delivery; Donald Frischmann, SVP, Communications and Brand Management; Greg Myers, SVP of Finance and CFO; John Thompson, Chairman and CEO; John Schwarz, President and COO; Gail Hamilton, EVP, Product Delivery and Response; Robert Clyde, VP and Chief Technology Officer. |

That was in June 2001, five quarters after John Thompson, a 28-year IBM veteran, had been recruited to “fix” the Silicon Valley software company. One quarter after becoming Symantec’s chairman, president, and chief executive officer in April 1999, Mr. Thompson announced a transformational strategy to take the company “upmarket,” from its roots in consumer software, to sell so-called enterprise systems, the software installations used by big corporations. He also promised to nearly double revenues, and break the $1 billion ceiling that separates minor software players from majors.

Conceptually, the strategy was a simple one. Symantec dominated the consumer market for personal computer antivirus software, programs that users install to help block bits of rogue code from invading their machines. Many companies already used Symantec’s antivirus product, but as large enterprises embraced the Internet, they would need more robust and more varied software solutions to keep their data safe and secure. Symantec’s strategy was to become the complete provider of security products.

But the real world has a way of intruding on the best-laid strategies of even the most capable leaders. As Symantec’s leadership team turned its attention to acquiring and building capabilities and products for the enterprise customer, the company’s consumer business was blindsided by a series of market disruptions that slashed year-over-year sales by 21 percent in the quarter ended June 30, 2001. “It was the darkest hour of my career because I knew the team had worked really hard,” Mr. Thompson reflected in a November 2002 interview at Symantec’s Cupertino headquarters. The setback “caused us to pause to think about how we were, in fact, going to manage ourselves in a very, very challenging time — a time when we had become confident in our strategy, but we weren’t really sure that the market was going to allow us to execute the strategy given where we were,” he says. “What’s even more relevant is, How do you recover? And how do you rebuild your credibility?”

How Symantec recovered and ultimately did deliver on Mr. Thompson’s billion-dollar promise is a lesson in the realities of corporate transformations. A strategy-based transformation is an opportunity to make a significant change and lasting improvement in the economic value of a company by taking it in a new direction using any number of different approaches — mergers, restructurings, new business models, new markets, or a combination thereof. Symantec’s transformation involved acquiring technology and management capabilities, learning new sales and marketing approaches, and skillfully positioning business leaders to drive change and execute strategy. “John came in and gave the company a greater sense of purpose by doing a small number of moves that seemed obvious after he did them. Some of it’s like Management 101, but his execution has been brilliant,” says Roger McNamee, cofounder and general partner of Integral Capital Partners, which counts Symantec among its 10 largest stock holdings.

But as the consequences of Symantec’s bad quarter show, a company in such a transition must be as resilient as it is flexible to recover from stumbles along the way. And recover Symantec did, taking its market capitalization from about $600 million to more than $6 billion within three years, even as the stock values of most software companies were plummeting.

Listen, Learn, Plan

Founded in 1982, Symantec was one of the earliest PC software companies, and a long-term survivor, even as once-brighter lights like the Lotus Development Corporation, Borland International, and WordPerfect dimmed or disappeared through acquisitions. Symantec produced a broad range of mostly acquired products, ranging from software development tools for programmers to ACT, the most popular contact management program. The 1990 acquisition of Peter Norton Computing Inc., maker of the leading antivirus product, Norton Utilities, cemented Symantec’s hold on the market for PC utilities, which are programs that help diagnose and fix disk-drive errors and perform other bits of computational housekeeping.

But by the end of the 1990s, Symantec’s sales and earnings were erratic; aggressive competition had eroded profit margins, and, after five work-force reductions in five years, morale was low. The company had largely missed the Internet boom. In the fiscal year ended March 31, 1999, Symantec shares were trading at about one times revenues, which then stood at $644 million. Other software companies were commanding five times revenues or more. That Symantec’s valuation was so low when Mr. Thompson joined the company was testimony to a company that had lost its way. “The situation was untenable,” says George Reyes, a Symantec board member and former vice president and treasurer of Sun Microsystems Inc. “It was either fix the company or continue to unravel and go into a death spiral.”

At that time, Symantec, with just more than 2,000 employees, had three business units: Remote Productivity Solutions, Security and Assistance, and Internet Tools. Remote Productivity encompassed fax software, the ACT contact manager software, and PC Anywhere, a software that allows users to connect multiple PCs. Security and Assistance products included Norton AntiVirus as well as programs for encrypting e-mails and keeping hard drives healthy. Internet Tools offered a set of software that developers could use to create interactive Internet sites and applications using the Java programming language.

Each of these business units had some market-leading products. However, the products had little in common besides a distribution channel, and even some of the popular programs were consistently unprofitable because of high development and support costs. Plus, customers did not closely identify the best-selling product, Norton AntiVirus, with the Symantec brand. In fact, the product still carried a prominent picture of Peter Norton, founder of the acquired company, on its box.

“Part of the problem was [Symantec] did too many things, and many of them not too well,” recalls Mr. McNamee. Mr. Thompson, who saw this problem immediately, pushed the company to focus on what it already did well, rapidly jettisoning weaker products, and even some strong ones, that fell outside his new strategy.

“The idea I had was I would just listen for 90 days, and within 100 days we would have a plan,” Mr. Thompson says. “But a couple of things became clear right away. The Internet Tools business had no linkage to anything else — we didn’t even use the product ourselves — and it was losing money. The company had no strategy for an Internet-based economy; there was no Web distribution, and there were no Web-based products.”

At an offsite meeting about 75 days into his tenure, Mr. Thompson brought together senior managers to determine the company’s new direction. The first decision was to concentrate on security, which was clearly the company’s strong suit. Another early decision was to restructure Symantec according to customer sets, rather than by products or geographies.

At the same time, a core leadership team, consisting of two Symantec veterans and two new recruits, was formed to drive change. Stephen Cullen, a senior marketing executive who had joined the company in 1996, was to lead the consumer business, and Gail Hamilton, recruited from the Compaq Computer Corporation, was put in charge of the new enterprise initiative. Rounding out the team were Symantec’s chief financial officer, Greg Myers, and a longtime IBM colleague of Mr. Thompson’s, Donald Frischmann, who was recruited to head communications and brand management.

The biggest challenge facing a change agent can be the task of gaining support from subordinates. As John P. Kotter of Harvard Business School notes in his recent book, The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations, “today, a single individual cannot effectively handle large-scale, fast-paced change alone. It is important to get the right people in place who are fully committed to the change initiative, well-respected within the organization, and have power and influence to drive the change effort at their levels.”

In driving the transformation of Symantec, the core leaders created four teams, composed of their respective direct reports, to look at markets, evaluate opportunities, and identify those with substantial potential revenues and long-term viability. The teams considered a diverse range of customers and markets, such as Internet service providers, the managed-services market, IT systems management, and remote PC connectivity. And through a collaborative process, they determined that the company would move aggressively into the corporate computer security market. “John set expectations, and he got key leaders involved in determining where we would go,” Mr. Cullen says. “It was easy for these leaders, because they were already working on these projects, to see our direction when we laid out all of the strategic alternatives. Then we made decisions and said how we thought they were going to impact the company.”

As Professor Kotter suggests, the team structure helped gain acceptance of these decisions throughout Symantec, even in pockets of the company where some of the least successful products still had intense support. Some decisions were easy, like spinning off the money-losing Internet Tools business, and some were harder, like selling the popular ACT program. But although ACT had defined the category of contact management for a generation of PC users, it had no connection to security, so Mr. Thompson felt it had to go. “It’s important when a company goes through a change like this to create some sense of focus,” Mr. Thompson says. “ACT, while profitable, did not grow very fast. It was a development and support distraction. Selling ACT helped people realize I was serious.”

Still, to be taken seriously in the enterprise security market, the company had to build or buy capabilities it lacked. “It went from top to bottom, there were so many things that needed to be addressed to make this transition,” says Ms. Hamilton, who had led enterprise units at both Compaq and Hewlett-Packard Company. “Immediately, we needed new development processes, with a level of performance testing and scale to ensure we were developing products that could serve hundreds of thousands of users,” she says. “Second, we had to establish a much closer relationship with customers. We needed to share our plans with them, we needed to understand their businesses and the problems they faced going forward rather than just immediate issues.”

Symantec’s needs were all the more urgent because as a company that published (i.e., packaged and marketed) software rather than developing its own, the company had no technological base, aside from the antivirus expertise acquired in the Peter Norton deal and some smaller technology acquisitions from IBM and the Intel Corporation. As a publisher, Symantec was hard-pressed to attract programmers, who at the time were being courted with big equity stakes in Internet startups.

Indeed, the software-publisher business, an intermediary model that had flourished in the early days of PC software, had largely disappeared with the consolidation of the industry and the spread of the World Wide Web, which let any enterprising programmer distribute his or her software directly to consumers. Companies such as Broderbund Inc., which resold independent developers’ programs, were gone. The might of the industry now lay with larger software developers that could leverage an essential technological base, as the Microsoft Corporation did with the Windows operating system, and the Oracle Corporation did with its relational databases.

A Serial Acquirer

Symantec had no time to build a technological base, so it had to buy one. The acquisitions had to follow the evolution of security needs. In the early days of the personal computer, hacker attacks were primarily associated with viruses, little programs that, like their biological counterparts, used their hosts to replicate — sometimes benignly, sometimes not. Security software used to be synonymous with antivirus software, and blocking these intruders was a simple matter of scanning for known code patterns. But because hackers have become more sophisticated, and attacks have mutated to include industrial espionage and potential terrorist actions, enterprises now face a broad range of so-called blended threats.

Combating these more varied threats requires a more varied, and more proactive, approach to security software. Vulnerability assessment programs help enterprises determine their risk exposure; intrusion detection identifies unauthorized uses of the network before they cause damage; virtual private networks and authentication services allow remote privileged users to get past the firewalls designed to keep intruders out. Security management keeps track of all these systems, chronicles security “events,” and distinguishes genuine threats from false alarms.

The only piece of this extensive puzzle that Symantec already owned was antivirus, so the company had to become a serial acquirer. Its historic strategy had been to buy disparate products to pump through its distribution channel; now each acquisition was intended to add a piece to the business portfolio and broaden its base in enterprise security technology. Each deal strengthened Symantec’s position in the security market; each added to the company’s technology base, and, perhaps even more important, to its talent pool.

“At that point in time, it was almost impossible for Symantec to hire anybody,” Mr. Thompson says. “We were not hip; we were a publisher, not a developer; we were not a dot-com; and we had a history of layoffs. My strategy was to acquire little companies, and pay about $1 million a head. I felt that would get us the talent we needed, and hopefully some technology, too.”

In February 2000, it acquired L3 Network Security, which offered products and consulting services designed to help enterprises assess their vulnerability to hacker attacks and rapidly detect systems intrusions when they did occur. Some of the world’s largest companies were already using L3’s Retriever and Expert products to design, implement, and manage network security.

Symantec followed that deal with an $18 million investment in Brightmail Inc., which makes products that enable service providers to manage and protect their e-mail systems. Symantec had previously partnered with Brightmail, whose technology filters messages to block spam and e-mail–borne viruses and could be extended to provide other forms of content control.

To enter the enterprise market, not only did Symantec need new engineering talent, it needed sales talent. The logistics of selling $100,000 products to corporations are vastly different from those of selling $100 products to consumers. And one of the critical differences between consumer software and the enterprise business is the sales channel. Symantec sold products such as Norton Utilities and ACT through big distributors, who in turn sold them to retailers who stacked the yellow boxes on shelves for consumers. Some of the products were also sold preinstalled on personal computers from such companies as the Dell Computer Corporation and Compaq. A limited number were sold by subscription, with upgrades delivered online.

In contrast, corporate customers are used to buying software directly from the manufacturer. Entry in this marketplace pitted Symantec against the well-trained sales forces of companies like IBM and Cisco Systems Inc., both of which are significant players in the enterprise security business. These companies also field armies of consultants and engineers, who generate additional revenues by aiding in the implementation of the programs they sell.

Symantec gained some of those capabilities, 750 people, and vital products and technology in the December 2000 acquisition of Axent Technologies Inc. for $990 million in stock. Axent’s Enterprise Security Manager and Prowler series were the industry’s leading vulnerability-assessment and intrusion-detection products, used by 45 of the Fortune 50. Axent also had the global reach of a network of qualified value-added resellers (VARs), as well as its own enterprise sales force.

For Symantec management, the deal was part of a logical transition. Initially, the company had focused on buying technology assets and engineering talent. With Axent, it was adding to its technology base yet again, and it was also moving into a new phase, by acquiring marketing and sales capabilities aimed directly at enterprise customers. “Early on we bought technical talent, not sales talent. In the second phase, the last two-and-a-half years, we’ve started to bring into the company people with strong direct-relationship sales capabilities,” says Symantec CFO Greg Myers.

But, following the series of smaller acquisitions, the Axent deal took Wall Street by surprise. Symantec’s market cap dropped by 28 percent the day after the announcement. “They didn’t expect me to do one that big,” Mr. Thompson says. “Also, there was a strong belief that Axent was damaged goods. They had a tough 1999, and appeared to be struggling against the competition. The reality was that Axent had some terrific technology and people who knew what we needed to get done. It was in my mind a transformational transaction, and it really did catapult our company’s enterprise strategy more profoundly than anything we had done.”

Nevertheless, Symantec could never acquire its way to sales or support parity with established enterprise software players. Instead, the company adopted a new distribution channel, which included creating a network of some 14,000 partners and introducing its first partner certification program. These partners, from large accounting firms and IBM itself to VARs, supplement Symantec’s small sales force and add their own implementation services.

The Axent acquisition was also the catalyst for changing Symantec processes to support an enterprise business. Axent had systems in place for serving major corporate customers, and just as important, its senior executives had an understanding of the service and support needs of that market. As the former Axent executives assumed leadership roles at Symantec, they helped guide the company’s investment in and deployment of new systems to undergird the new enterprise thrust.

As a global enterprise, for example, Symantec needed to become euro-compliant. It needed better overall enterprise resource planning (ERP) to make sure management was in control of critical processes. Because Symantec’s customer relationships had historically been with the distribution channel, not the end-user, it now needed end-user–centered systems to track problems and make sure they got solved, and to track relationships on a global basis.

Team Transformation

Not every executive bought into Symantec’s rapid change scenario, and those who did not were politely but rapidly moved out of the company. The leadership team welcomed it. Mr. Thompson says that increased turnover is actually desirable in a company undergoing a transformation. “Of the nine people who are on the senior management team, only two are left from the day when I arrived,” he says. “Today, we are just shy of 4,000 people; we had a little over 2,000 when I arrived. Of those 4,000 people, more than half have less than two years of service in our company. So, as we have retooled our strategy, we have completely retooled the team as well to work that strategy, because those two things in my mind truly go hand-in-glove.”

Some members of the new team came from acquired companies; others had been Mr. Thompson’s colleagues at IBM. But in many cases, Symantec’s key executives were senior people, like Ms. Hamilton, the former Compaq executive, who were recruited from market leaders. “John went out and got high-priced talented leadership and positioned them throughout the company,” says Greg Myers, one of the two remaining members of the old team.

Mr. Thompson also changed the compensation system. As a typical young aggressive technology company, Axent had based a large percentage of its compensation on stock options, which were allocated according to rank and performance. Because Symantec’s shares had long underperformed those of other Silicon Valley companies, it had compensated employees with higher-than-typical salaries, and perks, like BMWs. One of the ways the company aligned internal processes with the new strategy was to shift to a more incentive-based compensation structure.

“As a method for attracting and retaining talent, the prior leadership had used salary and cash compensation a little above the norm,” Mr. Thompson says. “As such, they had more assured compensation rather than risk-based compensation, higher than I expected for a team in a high-tech arena. Option grants were not related to the performance of an individual; it was more socialistic where everybody gets the same. So we lowered the base rate, but accelerated the growth rate.” Now employees get far fewer options to start, but gain many more, and more rapidly, if they exceed performance expectations. Option grants are also more heavily weighted to senior management than was previously the case at Symantec.

Mr. Thompson, no fan of distributed management, was quick to address organizational issues. At a time when many companies are implementing a “centerless” corporation organizational model, which is based on minimizing overhead and hierarchy while pushing critical decision rights to the periphery, Symantec has pulled those responsibilities back to corporate headquarters. Mr. Thompson blames the old structure, in which regions and business units each determined their own policies, for much of the old company’s lack of focus.

Centralized decision making means Symantec now has fewer meetings, with fewer people attending. “We used to have this monthly meeting with all the executive staff; everybody would show up in Cupertino from all over the world,” Mr. Thompson says. “We’d talk about issues and then people would go away and do whatever they wanted to do.”

“Strategic decisions are corporate decisions, not regional,” Mr. Thompson says. “It was time for some of our regional leaders to accept that they were part of a team rather than feudal lords.”

Mr. Thompson is also a bit of a contrarian when it comes to product strategy. Although individual PC users (and corporations buying PCs for employees) have largely given up buying a word-processor program from WordPerfect, a spreadsheet from Lotus, and a database from Ashton-Tate in favor of Microsoft’s all-in-one Office suite, enterprise customers select business-process software mostly by clinging to a best-of-breed approach. That is, corporations often buy what they perceive is the best application in each category, and let their internal information technology staffs integrate them. For example, they continue to buy human resource management software from PeopleSoft Inc., or CRM software from Siebel Systems Inc. and ERP products from SAP AG, rather than buying Oracle’s E-Business Suite. Symantec itself buys business applications in this way.

Security software has been purchased the same way. According to the International Data Corporation (IDC), security software includes security management, access control, authentication, virus protection, encryption, intrusion detection, vulnerability assessment, and perimeter defense. Symantec provides virus protection, firewall and virtual private network, vulnerability management, intrusion detection, Internet content and e-mail filtering, remote management technologies, and managed security services.

But Mr. Thompson believes companies will choose to buy an integrated security system rather than purchase antivirus from one vendor, firewall technology from another, and so forth. “Our strategy is different from every other security software company’s in the industry; we are not following a best-of-breed, point-product strategy,” he says.

The idea is that, although one vendor may offer a security component that outperforms a Symantec product, the cost and complexity of integrating multiple products outweighs any benefit to a corporation. This argument is similar to Oracle’s pitch for its E-Business Suite, which has yet to take significant market share away from the established players. It is not clear whether the enterprise security market will be any different.

“We buy best of breed when it comes to product,” says one customer, Jeff Moore, president of EcommSecurity Inc. in Atlanta. “We don’t recommend 100 percent of the Symantec product line.”

Ms. Hamilton counters, however, that most buyers of corporate security products are trying to reduce the number of vendors they deal with, but continue to buy from multiple sources. Although she believes Symantec’s offerings are competitive across the spectrum, she also stresses their ability to operate with other companies’ products. “Our strategy is not, ‘here’s a bundled suite that all works together, and take it, it’s all or nothing,’ ” she says. “It’s modular, and customers can take different pieces over time, blending our product with others.”

In any case, its product strategy appears to be working, allowing Symantec to claim the No. 1 spot in the $6 billion worldwide security market in 2002, with a 12 percent share, according to IDC. Using slightly different criteria, a November 2002 Gartner Dataquest report also shows Symantec as the world’s leading security software provider on the basis of new license revenue and market share in 2001. That report showed that Symantec’s market share of the worldwide security industry increased from 14.7 percent in 2000 to 21 percent in 2001, leading the list of the world’s top 21 security software vendors.

The Comeback

What happened in that wretched quarter back in 2001, and how did Symantec recover from it? Part of the problem was that while the company’s management was focused intently on its transformation goal to become a leader in serving the enterprise customer, the mainstay consumer business suffered. Some products were not upgraded rapidly enough to match competitors’ products, and the consumer unit’s marketing efforts remained diffuse.

More critically, a confluence of external events struck the company in that quarter. Worldwide sales for all consumer software went into recession; the dollar strengthened against the euro and the yen, negatively affecting the 45 percent of Symantec’s sales that came from overseas; and the company’s Macintosh-related business unexpectedly dropped 50 percent, possibly because of the perception that Apple Computer Inc.’s new operating system was less vulnerable to viruses.

“Most companies can suffer or endure one body shock in a quarter, but it’s unlikely a company can endure three,” Mr. Thompson says. “That made it very challenging for us to recover. We had to take some actions to shore up the business.” Some of those actions were obvious, like refreshing the consumer product line. Others seem counterintuitive, like raising prices on the basis of what turned out to be the correct hunch that the company’s primary competitor, Network Associates Inc., would follow suit to improve its own profit margins. At the same time, Symantec consolidated its marketing activities in a few key markets, rather than spreading them all over the globe.

Finally, Symantec got a boost from an unexpected quarter: hackers. Highly publicized viruses, like Code Red and Nimda, coupled with heightened security awareness of all kinds after the attacks of September 11, 2001, led many customers to consider Symantec’s products for the first time.

“We did get the benefit of what I’ve called the most insidious, malicious code environment in the history of the security industry over the last two years,” Mr. Thompson says. “No one could have ever forecast the level of activity by hackers and virus writers that we’ve seen. And we’ve just been reasonably well positioned to be able to take advantage of that when it did occur.”

Sales growth in the September 2002 quarter was 7 percent, jumping to 20 percent in the December 2002 quarter. For fiscal year 2002, which ended on March 31, Symantec’s sales grew 14 percent, to $1.071 billion, with earnings of $65.1 million, or 41 cents a share.

This strong performance has continued. For the fiscal second quarter 2003, ended September 30, 2002, Symantec posted revenues of $325 million, a 34 percent increase over the year-earlier quarter. Pro forma net income before one-time charges and the amortization of acquisition-related intangible assets was $60 million, or 38 cents a share, compared with $42 million, or 28 cents a share, for the same quarter a year earlier.

A Suite of Challenges

Still, challenges remain. Old competitors, like Network Associates, Trend Micro Inc., and McAfee, are rapidly following Symantec’s move to the enterprise market. Established enterprise players, such as Computer Associates, Checkpoint Systems Inc., and Cisco, are ceding little ground. Firewalls are a natural product for a network systems vendor such as Cisco, which can build them into its servers at very little additional cost, and Computer Associates can easily add security processes to its systems management software, in much the same way Microsoft has slipped features from Norton Utilities into Windows over the years.

Symantec has continued to buy companies, rolling the acquired technologies into its security portfolio. This strategy presents two challenges. The first is the cultural challenge created by any acquisition; the second the technical difficulty of integrating products created by disparate development teams.

On cultural matters, Symantec treads a middle line between the laissez-faire approach historically used by Novell Inc., which allowed acquired companies to retain much of their own cultures and many of their own processes, and the strict discipline of Cisco, which erases the old company’s identity and plants the Cisco flag the day the deal closes. Symantec’s flexible approach is visible in small ways, like the shorts and flip-flops favored by employees at the former Santa Monica home to Peter Norton, which contrast with the khaki culture of the Silicon Valley headquarters.

“We have a pretty aggressive integration process, but we’re not at the point where we say you have to think the Symantec way,” says Robert Clyde, Symantec’s vice president and chief technology officer, who joined with the Axent acquisition. “We show up the next day with the benefit packages, with as many answers as we can, because it’s uncertainty that causes the most pain.”

With respect to the other challenge, integrating products created by disparate development teams, Mr. Clyde says the technical integration of the acquired products has been simplified by something called the Symantec Enterprise Security Architecture. “Rather than every product integrating with every other, with each acquisition, we move products onto that common architecture,” he says. “It’s phased, so there’s some easy integration that happens right away, and the more difficult stuff takes longer. This way we can integrate acquired products quickly.”

The pace of migration away from the Norton brand is another issue for Symantec. The company’s leadership would like the entire product line branded with the Symantec name, and the enterprise offerings all are, as in Symantec Enterprise Firewall 7.0, Symantec Enterprise Security Manager 5.5, and so on. But the consumer products all still carry the Norton name; their yellow color, which Peter Norton adopted so his boxes would stand out on store shelves, is now Symantec’s official hue. The Symantec name is gradually getting bigger on the boxes, and Mr. Norton’s face is gone, but even many enterprise customers still know the company primarily as the publisher of Norton products.

“There were suggestions that we change the name of the company to Norton, but Norton is very heavily associated with $29.95 products,” says Mr. Frischmann, Symantec’s senior vice president of communications and brand management, a 30-year IBM employee who was Mr. Thompson’s first executive hire. “We’ve accomplished a lot by associating Symantec with the enterprise. We’ve made a few steps toward moving Symantec into the consumer market, but we’re moving slowly. I believe we can have one brand, but it could take five years or more,” he says.

Five years in the software industry is a very long time. Although the Norton products don’t command the six- and seven-figure price tags of the enterprise offerings, or the healthy profit margins, they do generate a tremendous amount of cash flow, and Symantec is not going to make the branding change until they know their position in the consumer space is secure. Despite the focus on the enterprise, the consumer business is still growing at a faster rate. In the quarter ended September 30, 2002, Symantec’s worldwide enterprise security business grew 30 percent from the same quarter the previous year and was 44 percent of total revenue, while the consumer business grew by 68 percent during the same period and was 38 percent of total revenue.

Analysts differ on whether the continued importance of the consumer business is a problem for Symantec. Whereas some view it as a weight slowing the enterprise initiative, others see it as fueling the whole company’s growth.

“While the enterprise opportunity is the bigger one over the long term, the consumer market is still under-penetrated, and nobody can compete with Symantec, given the company’s 70 percent share of the market today and their strong brand with Norton,” says Jonathan Ruykhaver, an analyst with Raymond James. “The strength of the consumer business has allowed Symantec to be acquisitive, to buy some strong emerging technologies. It gives them the opportunity to educate the enterprise market and capture that opportunity over time.”

Others say Symantec should move away from consumer products, which sell at very low prices, but still require a high level of technical support. “All they have in that space are products that are painfully hard to support at the prices they’re getting through retail,” says Jeff Tarter, editor and publisher of Softletter, an industry newsletter based in Watertown, Mass. “They get that $15, but they have to be constantly finding viruses, fixing them, making the product better than McAfee. If they had any sense, they’d get out of the consumer business, but they can’t.”

Mr. Thompson says this view is simply wrong. “There’s no question the consumer business is growing faster at this moment, but at a time when the enterprise software business around the world is contracting, ours has grown 30 percent,” he says.

Of course, 34 percent revenue growth and 43 percent earnings growth are problems most software companies would love to have right now. Mr. Thompson says he is not concerned about the pace of change or the big players Symantec will increasingly face as his strategy proceeds.

“Companies that win in this industry are willing to make big bets, and they’re able to get their team rallied behind what they’re trying to do,” Mr. Thompson says. “The fact that somebody bigger than you has an idea doesn’t mean you should run away from it. I can outrun. I can outthink. I can outexecute. If you can do these things, size doesn’t matter.” ![]()

Reprint No. 03108

| Authors

Lawrence M. Fisher, lafish3@attbi.com, covered technology for the New York Times for 15 years and has written for dozens of other publications. Mr. Fisher, who is based in San Francisco, is a recipient of the Hearst Award for investigative journalism. |