Companies that change the game can change the world

How exponential models can enable businesses to attack societal problems.

The world faces a host of existential crises, including climate change, natural scarcity, income inequality, and poor global health. We call these exponential crises because they are characterized by a series of feedback loops that create vicious circles. And, in turn, they aggravate one another. Poverty leads to a lack of access to healthcare, which exacerbates the health crisis. Climate change leads to food insecurity, which leads to greater poverty and amplifies the crises that stem from want. What’s more, these crises are intensified by powerful threat multipliers that are deeply embedded in our industrial and social systems—for example, CO2 emissions aggravate climate change. These threat multipliers can prevent the forces seeking to solve the problems from scaling up.

Have you heard enough bad news? There is some good news. The solutions to these exponential crises—or at least components of the solutions—are at hand. And if they are properly harnessed by the principal organizing agency in our world, they can lead to transformative progress. There is a broad sense that business, in its pursuit of profits and the usual modes of operation, has created and exacerbated many of the crises. But that reflects a view of both the potential and the purpose of modern business that has long been out of style. Whether it was the mechanization of agriculture solving the problem of scarcity, the advent of electricity providing immense benefits to people’s quality of life, or the computer revolution enabling much greater connectivity, business developments have always contributed to the solution of society’s problems.

That pattern—the ability of business to solve social problems—is the basis of a research project we have undertaken to gain a systematic understanding of just how this dynamic can play out, and what sums are at stake. And it is clear to us that under certain conditions, business can in fact be the source of great progress and solutions while doing what it does best: innovating, investing, developing compelling products and services, and executing. In short, with the right technology and the right business model, and in working with the right counterparts in the right way, businesses can enable prosperity and health while creating and capturing immense value. The companies that can do this best are what we call the game changers. Game changers address an exponential problem by using exponential technologies, developing exponential business models, and working in ecosystems. Pursuing this path—and not incremental improvement, or deals, or efficiencies—is one of the best options for value creation and transformation in our world.

Exponential technology, exponential business models

In many areas, as techno-optimists like to point out, we have the tools and resources at our collective disposal to deal with these crises. The world’s land can theoretically produce enough food to eliminate hunger. Putting solar panels on just 22,000 square miles of the US—0.6% of the country’s landmass—could power the entire nation (provided, of course, there are batteries sufficiently large to store electricity for when the sun goes down). The technology tool kit available to us today is far more potent than any before. Artificial intelligence, data analytics, the internet of things, automation, sophisticated collaboration and communication tools—these exponential technologies, which continually fall in price, enable the rapid and economically efficient scaling of powerful solutions. Moore’s Law is a representative construct of how and why these technologies can create far-reaching impact when embedded in the right solution sets. Consider that the iPhone today puts exponentially more computing power in the pocket of a young woman sitting in a café in Jakarta than was in ENIAC, the massive first supercomputer developed in the 1940s.

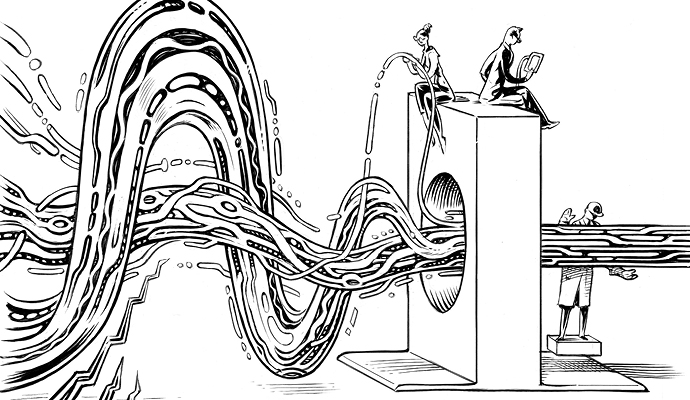

Technology is just a tool—a powerful one, but a tool nonetheless. In order to really make a difference, to overcome the negative feedback loops of exponential crises and the powerful countervailing anti-scaling forces present, exponential technology has to be married to, and integrated with, an exponential business model. Simply attaching a jet engine to a vehicle won’t ensure that it will fly safely. Technology has to be melded with an effective strategy for development, deployment, innovation, and iteration.

Simply attaching a jet engine to a vehicle won’t ensure that it will fly safely. Technology has to be melded with an effective strategy for development, deployment, innovation, and iteration.

An ecosystem approach

And there’s one more piece of the puzzle. Marrying exponential technologies to exponential business models isn’t alone sufficient. In order to really do their work in the world and create value, game changers have to work within ecosystems, encouraging other investments that make their own products and services more viable and compelling. The onus of, and opportunity for, innovation doesn’t fall on a single party. Rather, much as Apple has done, companies can create opportunities for others to add their own ideas, capabilities, tools, and products and services. In ecosystems, as compared with the typical supply chain model, value is created through opening more channels: by recruiting more users, increasing the size of the market, and making consumer information and demand more transparent. Working through ecosystems lends credibility to solutions and creates positive feedback loops that ultimately push scale. Supply chains move consumer data through the supply chain. But in an ecosystem model, the consumer data—the numbers of orders for soap, the prescriptions a consumer is taking—is available to multiple players. As they work in ecosystems, game changers may work as orchestrators or integrators to deliver outcomes. Some may even work as platforms (see “Platform players,” below).

Another example of a game changer operating in this mode is likely Tesla. It has sought to solve the exponential problems of climate change and mobility. It has adapted a series of exponential technologies—not just batteries and solar panels, which have made quantum leaps, but AI, autonomous driving, and software. It has created a unique and divergent business model that allows it to scale: direct-to-consumer sales, its own network of “gas” stations, and ancillary businesses in energy storage and home-based solar power. And it works in a vibrant ecosystem. Tesla’s growth has led to massive investments in charging infrastructure, software, and products that optimize electric mobility and renewable energy.

But the power of game changers isn’t limited to computers and mobility. In our research, we have examined companies operating in a variety of industries, including power production, healthcare, chemicals, retail banking, educational technology, and agriculture. Their stories aren’t always neat, but the underlying argument holds across industries. In this article, we take a look at how it can play out in the US sector of the vast global healthcare market.

The healthcare opportunity

US healthcare is the arena in which we have done the most intensive work and modeling. In the United States, the world’s largest economy, healthcare represents about 20% of GDP. Healthcare is plagued by many exponential problems, most notably unaligned incentives. Broadly speaking, the US spends a huge (and rapidly rising) amount of money on healthcare—US$4.3 trillion in 2021. And the results are less than impressive. Indeed, in the wake of covid-19 and a number of other persistent health challenges, US life expectancy has actually fallen in the last several years, to 76.1, the first decline of this magnitude in 80 years. Fee-for-service healthcare incentivizes health systems to deliver more, higher-acuity care, or at the very least, removes the disincentive to balance additional care against the costs to deliver it. Care delivery, especially at higher acuity levels, necessarily has to take place in person. The graying of America adds both demand and complexity to health management. By 2030, 20.1% of people in the US will be over 65, an increase of more than 18 million elderly people from today’s levels. Beyond the continuing effects of covid-19, the US system is dealing with epidemics of obesity, diabetes, drug use, and cancer.

Of course, the ability to treat both the symptoms and the causes of the US health crisis exists in many cases. But several classic anti-scalers are present that prevent solutions from rolling out effectively. These include subpar consumer experience and low levels of trust; opacity in price, data, quality, and outcomes; a general resistance to change in a stressed environment; and financial incentives. At the same time, several exponential technologies have applications to this sector, including digitization and the incorporation of AI and automation into the care-delivery process.

All of this means there is a great deal to be gained for all parties if business can solve this societal problem. According to our forecasts, US$1 trillion in financial value is at stake over a five-year period (through 2027) if the healthcare system can move to new, more effective models. For society, we believe there is an opportunity to create a US$200 billion consumer surplus over five years (through 2027) through lower healthcare costs. Such efforts will likely also result in improved experiences and outcomes.

We are starting to see some work in using exponential business models in the US healthcare ecosystem. There are two model types that offer the largest potential for value creation in this scenario: orchestrators and integrators.

Orchestrating better experiences

Orchestrators advocate for consumers and guide them through the healthcare journey, ensuring seamlessness and coordination across a network of care-delivery entities. Orchestrators influence care delivery by redirecting patients to high-performing, efficient sites of care. They are able to deliver a leading consumer experience, earn consumer trust, and leverage AI to enable informed consumer choice.

The value at stake here is immense. Depending on future scenarios (involving the extent to which consumers/funders versus incumbents reshape the industry), orchestrators are expected to garner US$150 billion to US$230 billion of revenue and direct another US$1.2 trillion of revenue (approximately 30% of the total industry) by 2027. This will make them the gateway and guide to the healthcare system for a significant proportion of the US population.

CVS, for example, is making major investments in an omnichannel care-delivery platform centered on what it calls HealthHUBs. Since its 2017 merger with the giant insurer Aetna, CVS has evolved from attempting to sell insurance to trying to get more people into its stores to access products and services. HealthHUBs offer insured customers an in-store meeting with a coach who can lead them through the whole healthcare experience. The value proposition is twofold. First, once a company can start to orchestrate the experience, it can better manage the overall health of an individual—and hence lower medical costs through value. Second, the improved experience drives loyalty and creates greater stickiness. People who have a positive HealthHUB experience will be more likely to fill prescriptions and shop at CVS stores, and continue to stay with Aetna—which covers many of the services there—for their insurance. In this instance, the orchestrator makes money through charging premiums, lowering costs, and getting greater sell-through for the business. CVS wants to function as a front door into the system, directing individuals to where and how they seek care. It is deploying AI and advanced analytics to send consumers to the right places in its pharmacy, retail, and health insurance businesses.

Startups such as Accolade Health, a pure-play orchestrator, represent another approach. Accolade works with self-insured employers, including large organizations such as PwC. It specializes in claims, processing the paperwork and then using the volume of claims it handles to get discounts with big providers. The company also can assign a care advocate to clients’ employees who will effectively orchestrate their healthcare—whether that means finding a dietitian or figuring out how to get reimbursed for a gym membership. Accolade charges a flat rate per person covered and promises to deliver a lower medical cost, passing savings on to the customer. The company connects individuals to a care advocate, who is then informed by algorithms that suggest, after examining patients’ medical records and behavioral preferences, the best course of action—such as sending someone to urgent care instead of a primary care doctor because he works two jobs and needs after-hours service.

Although outcome data is limited, orchestrators are beginning to demonstrate efficiency improvements and have proven their ability to capture consumer loyalty. Accolade, for example, boasts an industry-leading Net Promoter Score (70-plus NPS for advocacy leaders).

Orchestrators can harness data and information to provide advice to consumers, and can use the power of consumer decision-making to push industry participants to work within certain specifications. If an orchestrator knows a patient with knee pain already had an MRI on the knee and nothing has changed since that scan, they would recommend that the physician treating the patient use the existing MRI; similarly, they could recommend that the patient have knee-replacement surgery at an outpatient center instead of a hospital. In a world where consumers are increasingly responsible for expenses, this information becomes more powerful. And it forces providers to share quality and cost metrics.

The integration play

Integrators own care delivery across channels and meet consumers’ care needs across their journey. They typically manage a closed, vertically or virtually integrated network that focuses on a specific geography (e.g., Kaiser Permanente in California), disease state (e.g., Omada Health for diabetes), or consumer segment (e.g., Humana for the Medicare market). We expect integrator models to deliver approximately US$1.5 trillion to US$2.2 trillion in revenues of the US$3.6 trillion healthcare industry in 2027. This reflects a 75% increase from present levels, and will make integrators the predominant model of care delivery in the country.

Integrators change the game by aligning the value chain’s incentives toward better outcomes and experience, and lower total costs. The vertical integration option promises a constant healthcare price point to the ultimate payor, whether that is the employer or the government, and aims to minimize healthcare costs within that price point. Integrators strive to deliver a low total cost of care, better population outcomes, and a coordinated and seamless experience within their network. They are especially incentivized to make these investments because they are at risk for covering the bulk of medical costs in their markets.

Integrators can also achieve the incentive alignment and technology integration needed through value-based contracting supported by a common stack of enabling technologies. This approach has been gathering steam over the past ten years, driven by shifting Medicare reimbursement models that require health systems to invest in care management and population health, and by fluctuating or declining health system performance, especially during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported a savings of US$4.1 billion to date due to value-based care models and is continuing to expand them. That represented a 4% savings on spending through those providers. Those savings, if extrapolated to the entire hospital-based healthcare system, would be substantial.

The virtual integration option replicates this approach without a single entity owning the value chain, and instead sets the right financial structure to each transaction in the value chain. In this world, insurers or providers work on capitation payments—that is, they receive a flat rate per person per year for all healthcare spending. As a result, they have incentives to invest in the types of initiatives that have been proven to reduce healthcare utilization, in part by focusing on the social determinants of health.

In its work with a large provider, PwC has used its proprietary body-simulation technology to help decide whether a US$400 million investment in social determinants of health should go into building urban groceries or improving housing.

Humana focuses on a specific market segment—the vast Medicare population of Americans over the age of 64—and has assembled capabilities geared toward this population. The company has built up middle-office capabilities dealing with care management and utilization management. Because seniors are most likely to trust doctors on healthcare, the company deploys value-based models with primary care physicians to incentivize them to manage the full-care journey for seniors. And because care can often be delivered to seniors more efficiently at home, in 2021, Humana acquired Kindred at Home, a leading player in the home health sector. At roughly the same time, it acquired onehome, which specializes in value-based home health.

Platform players

Platform players represent the data, analytics, and experience “spine” of connected health ecosystems. The opportunity here is smaller than in other sectors. Although this segment of the market has been growing significantly, at a 15 to 20% CAGR since 2016, and is expected to continue doing so, the total market will amount to only about US$90 billion by 2025. Still, platforms play a vital enabling role. Players build the standard capabilities—electronic health records, or integrated real-time clinical data—that allow solutions providers to plug into the platforms that enable them to scale. Platform players implement the AI, automation, or analytics use cases necessary to bring connected health ecosystems to life. One of the leading players in the platform sector is Epic Systems, which owns the largest electronic health platform in the US and stores the medical records of about 200 million Americans. Healthcare utilities have standard levels of demand growth, similar to electric utilities.

Shifting the mindset

Our research in understanding the role of game changers—in healthcare and other industries—is just beginning. And as we look ahead, the importance of such companies will grow. The challenges our society faces continue to intensify. As recent experience shows—whether it is in battling the covid-19 pandemic or fighting climate change—government policy alone can’t effect the necessary change.

Companies in a broad range of industries have the potential to adopt the mindset of game changers in order to create value. And although it is difficult for any incumbent to simply come out of a strategy session with a flawless plan to align its business model with the solution of societal problems, there are several concrete steps organizations can take.

They start with a shift in companies’ mindset about solutions. Companies must envision how the solution of global crises can resolve into workable consumer solutions. Rather than focusing exclusively on short-term growth, organizations should prioritize delivering those solutions in the market. And when it comes to impact, rather than checking off sustainability metrics or comparing benchmarks, they should examine how they and their industry are contributing to the mitigation of crises.

Companies that manage to change the competitive dynamics in their industry are making focused, significant bets on technologies and capabilities that give them an edge. And they continually capture data, run simulations, and analyze performance so that they can respond more quickly to the demands of customers and society. Changing the game—regardless of the industry—requires an integrated approach toward continuous improvement.

Author profiles:

- Sundar Subramanian is the US and Mexico leader of Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business. Based in New York, he is a principal with PwC US.

- Anand Rao is PwC’s global leader for artificial intelligence and innovation lead for the US analytics practice. Based in Boston, he is a principal with PwC US.

- Harshavardan Kasturirangan advises healthcare clients for Strategy&. Based in Chicago, he is a director with PwC US.

- PwC senior associate Sandhya Rajagopalan also contributed to this article.