How India can live up to its full potential

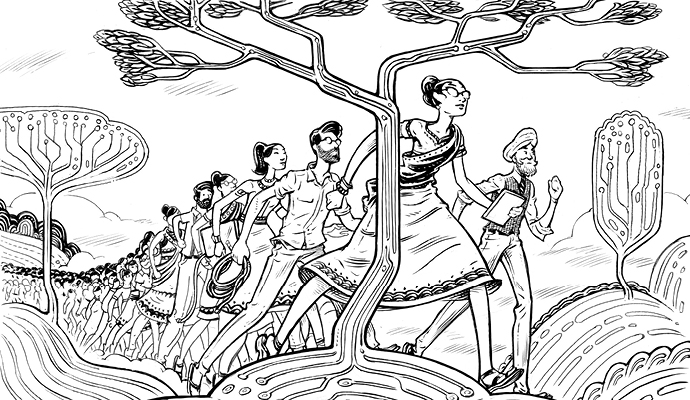

By eliminating frictions, the world’s largest democracy can generate higher and more inclusive growth.

In a remote tribal village in Dumarthar in the state of Jharkhand, Sapan Patralekh, the headmaster of a middle school, has come up with an innovative teaching method in a region plagued by poor connectivity. He has converted the walls of adjacent houses into blackboards, allowing 300 students to continue learning while maintaining social distance.

In crowded cities, traditional mom-and-pop convenience stores and pharmacies have begun to provide contactless home delivery. Startups such as Near.Store are rolling out plug-and-play solutions to digitize traditional neighborhood convenience stores, allowing them to accept orders and payments online for groceries, medicine, and healthcare essentials, as well as making offline inventory digitally searchable by customers who live within walking or biking distance. OkCredit is using digitization to send collection notifications to customers who have delayed or missed payments, decreasing the burden on shop owners of maintaining business accounts.

On the B2B front, Bulk MRO, a venture-backed startup in Mumbai, has created a seamless marketplace interface that allows corporate customers to meet MRO (maintenance, repair, and operations) needs — in a touchless mode with only a single vendor. With its business growing at an annual rate of 200 percent, Bulk MRO serves nearly 250 large companies, 40 of which are in the Fortune 500.

In ways large and small, the pandemic has radically accelerated the pace of innovation and transformation in India, prompting organizations of all types and sizes to reconfigure their relationships with their customers and stakeholders. Indeed, with more than 480 million internet users and 1.17 billion mobile phone subscribers, India stands at the precipice of a national digital transformation. The pandemic, while spurring innovation, has highlighted a perennial challenge: Powerful systemic and structural frictions continue to hamper the development of demand, supply, resources, and institutions. However, we believe that India’s economy — powered by digital technology, augmented by physical infrastructure, and supported by an alliance of government, citizens, and enterprise — can steepen its growth trajectory. By drawing on a full-potential mindset, the country can seize this opportunity as it approaches the 75th anniversary of its independence.

Full-potential mindset

What do we mean by the full-potential mindset? Why does it matter? And how do we achieve it? The answers to these questions can be found in a recent comprehensive PwC India report, Full potential revival and growth: Charting India’s medium-term journey, from which this article is adapted. In our report, we examined the nine key sectors that make up 75 percent of India’s GDP, and discussed government policies and social and economic trends. We believe that in every individual, organization, and country there lies hidden potential that can be brought to light through a new event, shock, or sudden change in circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic has been one such shared event. The Reserve Bank of India projects the Indian economy will be found to have shrunk by 10 percent in 2020. (The highly informal nature of much of the Indian economy implies the contraction was actually deeper.) A stringent lockdown amounting to 175 billion person-days may have contributed to this decline, but it has also ensured that the country’s COVID-19 caseload was relatively contained. As was the case elsewhere, the unprecedented health crisis and the shared experience of 1.35 billion citizens triggered deep introspection among citizens, organizations, and governments.

The pandemic has radically accelerated the pace of innovation and transformation in India, prompting organizations of all types and sizes to reconfigure their relationships with their customers and stakeholders.

As a first step, all sections of society — government, enterprise, citizens — have now begun to focus on reviving and boosting demand. The International Monetary Fund expects India’s economy to grow by 11.5 percent in 2021, making it the only major country with a double-digit growth forecast. But there’s something potentially deeper at work. The national and regional lockdowns resulted in visible changes in consumer psychology and demand patterns, which have driven the need to innovate. Shifting operating models and supply chains are also much in evidence. And given the slowdown, new resources and tools have been marshaled for unlocking new growth avenues. Across all segments, sectors, and geographies, this crisis has brought to light frictions that beset the Indian economy. Overcoming these frictions can trigger rapid revival and subsequent growth.

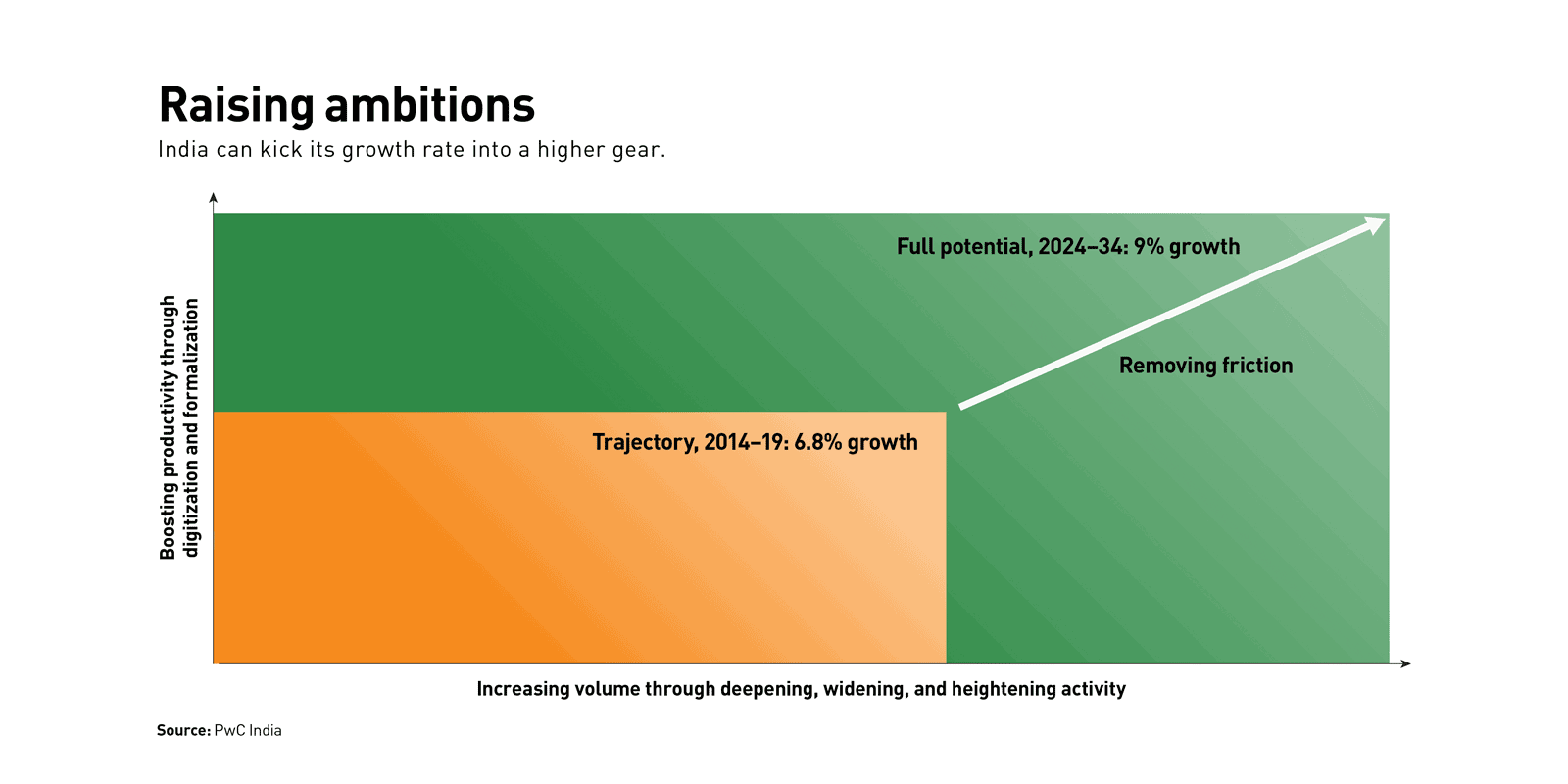

Several years ago, in Future of India: The winning leap, a report published by PwC India, we forecasted (in collaboration with Oxford Economics) three economic growth scenarios for a 20-year period starting in 2014. These scenarios included a 6.6 percent annual rate, driven by basic infrastructure investment; a rate of 7 percent, based on additional spending on physical and digital development; and a 9 percent “winning leap” growth rate that rested on unlocked productivity, stronger R&D, and financial reforms.

In the five years before COVID-19, India’s economy grew at a 6.8 percent annual rate — somewhere between the first two scenarios. We believe that the largest democracy in the world, a US$2.9 trillion economy with a median age below 30, can create growth that is higher, more inclusive, and more sustainable. If India can maintain the full-potential growth rate between 2024 and 2034 and grow at 9 percent per year, it would create an additional cumulative $10 trillion of economic activity and set an example for the world. And it would help fulfill India’s near-term vision of building a $5 trillion economy more rapidly.

We identify five key frictions that are holding India back — all of which were exposed by COVID-19. The first is the lack of depth — the extent to which the economy remains concentrated in urban and metropolitan centers. The second friction is a lack of width in the economy. States mostly in the west and south of India, with 48 percent of the population, account for about 70 percent of GDP, while others, the central and eastern states that we refer to as the hinterlands, account for only 30 percent of GDP, even though they are home to 52 percent of the population. Even within states, distribution of economic activity is concentrated in selected top districts. A third friction is what we refer to as the height of the economy. India exports plenty of goods and services, but its efforts are limited by infrastructure, and only certain parts of the country truly participate in the global economy. India, like many other countries, suffers from a substantial digital divide — the fourth friction. The final friction is the extent to which India’s economy remains informal; this informal economy represents about 50 percent of GDP.

Throughout India, governments and organizations are seeking to lift the constraints on the economy in two ways. The first is related to the volume of economic activity, which can be achieved by deepening, widening, and heightening activity. The second is related to improvements in productivity by formalizing and digitizing the economy (see “Raising ambitions”).

Boosting volume

At root, boosting economic volume means ensuring that more people among India’s 1.35 billion–strong population become involved in production and consumption. By supporting one another, India’s key sectors can build powerful platforms for growth involved in production and consumption. The crisis response of governments the world over has been unprecedented, with almost $10 trillion in stimulus announced in just the first two months of the pandemic. On the whole, India’s direct fiscal stimulus efforts paled in comparison to those of large, developed economies. Many countries devoted substantial chunks of GDP to crisis-response stimulus: 33 percent in Germany, 21 percent in Japan, and 12 percent in the United States. By contrast, India’s direct fiscal stimulus (barring long-term liquidity and credit measures) amounted to about $70 billion, or less than 3 percent of GDP. India, along with other emerging economies, has limited budgetary firepower to support the economy during a very sharp contraction. But the country can use its core technological strengths to deploy smart stimulus that directs money to targeted segments for maximum impact, and can enable infrastructure that creates a multiplier effect and boosts economic volume.

As an example of increasing the volume, the government in mid-2020 announced a $1.94 billion financial package for the Indian pharma sector to incentivize the local production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Recognizing the impact of global supply chain disruptions on India’s vast pharmaceuticals industry, the initiative aims to provide production-linked incentives while expediting environmental clearances. The package includes incentives for 53 APIs and the construction of several mega-parks for manufacturing. This initiative is being seen as a “Y2K moment” for Indian pharma. The country is aiming not simply to overcome its own healthcare crisis and upgrade its health infrastructure, but also to provide cost-effective medicines to the rest of the world and play a more prominent role in the global pharma supply chain. As new vaccines are developed and introduced, India, which is already the vaccine production capital of the world, is gearing up to play its part.

One of the key goals of boosting economic volume is to enable more people to thrive where they live, rather than having to migrate to find work and opportunity. Accordingly, a large part of the government’s COVID-19 stimulus has been directed at India’s hinterlands. And as many workers returned from large cities to their home villages and districts in the wake of pandemic shutdowns, there was a natural decentralization of consumer demand. India can further deepen the economy by encouraging both production and consumption to follow people into smaller towns and districts. Volume will also be created if India widens the economy by creating infrastructure and economic opportunities in the country’s north, center, and east. A third way to create volume is to heighten the economy by encouraging and enabling people and organizations outside metropolises to export and participate in the global economy. This can be accomplished by providing necessary infrastructural support and resources.

Improving productivity

Digitization and formalization are important levers for boosting productivity. India has made enormous progress in digitizing the economy over the past decade, and the country has a strong baseline of technology adoption. Many technology-driven businesses — especially in healthcare, IT, and education — are thriving, and smartphone penetration and internet penetration are remarkably high. Our research suggests that further enhancing data sharing, linking technology with regional languages, and creating platforms can enhance both the efficiency and the effectiveness of the economy. E-education is expectedPDF to grow at a compound annual growth rate of greater than 50 percent. The increased adoption of such programs can break geographic barriers and provide equal learning opportunities across geographies and segments of the population. Amid the pandemic, 14 Indian ed-tech startups raised funds. And an estimated 4,800 health-tech startups are leveraging cutting-edge technologies to help fight the pandemic in India.

Startups are also investing in supply chain solutions, which represent another area of great potential for productivity improvement. Simply put, it takes a long time and costs a lot of money, on a relative basis, to move goods around and from India. It takes 41 days for a consignment of apparel to move from Delhi to Maine. In India, logistics expenditure accounts for 13 to 14 percent of GDP, compared with an average of 9 to 10 percent for developed economies. The overdependence on road transportation and under-penetration of cost-efficient rail and inland waterways were exposed during the pandemic. Greater use of freight trains during lockdown, on the other hand, showcased the advantages of multimodal transport to enable end-to-end logistics solutions. The draft National Logistics Policy, released in 2019, aims to reduce the modal share of the road network from 60 percent in 2017 to 25 to 30 percent in 2030.

Recovery through a wider, deeper, more productive, and more digitally enabled economy is interlinked with the “two-tone” structure of the Indian economy, which is typical for emerging economies. The top layer includes about 12 percent of the population. These are people who speak English, and many of them work at white-collar and blue-collar jobs in formally organized companies. The bottom layer, about 87 percent of the total labor force, is made up of people who speak one of India’s many local languages and work in the informal sector. The pandemic has highlighted how India needs to focus on this two-tone recovery across the nine key sectors that make up 75 percent of the country’s pre-pandemic GDP: health and pharma, financial services, power and mining, consumer and retail, infrastructure and logistics, industrial products and automotive, technology and education, government, and agriculture.

Formalization will ensure that many smaller businesses that are not currently participating in the market economy will be brought in, through policy measures, increased ease of doing business, and enabling platforms. On a geographic basis, the next wave of growth is expected to come from the semi-urban and rural centers of India, which also account for a significant share of the informal micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Currently, MSMEs have a low level of digital adoption, with only 11 to 13 percent deploying productivity enhancement solutions and less than 1 percent using sophisticated technology such as robotics or IoT. This presents a major opportunity for digital adoption, with the bulk of demand arising from MSMEs in the retail, manufacturing, education, and hospitality sectors.

The temporary stoppage of economic activity as a result of the pandemic and ensuing lockdown have intensified the need for capital among MSMEs. But a large share of MSMEs (79 percent) are unregistered, limiting their ability to get formal credit. Most MSMEs find it difficult to produce collateral, credit history data, and documentation such as financial statements that are typically required for loan requests. As a result, around 90 to 95 percent of MSMEs rely on informal credit sources.

Increasingly, technology companies are offering products pitched directly to MSMEs. For example, Zoho, an enterprise solutions company based in Chennai, says that MSMEs make up 85 percent of its approximately 100,000 customers. Zoho offers free accounting solutions to MSMEs with an annual revenue of less than $200,000. As demand from the sector grows, technology companies could tap into this segment by curating products aligned to their needs, developing digital platforms, and building ecosystems that collectively enhance their reach and productivity.

Powerful platforms

Unless demand, supply, resources, and institutions are addressed together, any revival will be slow. Platform business models have demonstrated the power of rapidly enabling scale, growth, and outcomes with far fewer resources than traditional models — in large part by involving multitudes of customers or citizens in the value creation process. They do so not just by disrupting the traditional value chain, production, and marketing models, but by creating an ecosystem that empowers both consumers and suppliers. And they drive faster adoption by setting common standards to allow businesses and institutions to scale up. Spurred by the COVID-19 crisis, India is adopting a similar approach to reach out to more citizens, engage enterprises, and develop policy measures.

Over the past decade, India has created technology platforms to drive transformation in sectors, industries, and the lives of citizens. Unified Payments Interface (UPI), a seamless real-time payment system interoperable through a virtual ID, mobile ID, or bank account, and Aadhaar, a 12-digit unique identity authentication number for every citizen, have been at the vanguard of the country’s ability to deploy platforms to solve the problems of formal identification, financial exclusion, and marginalization. Monthly transaction volumes through UPI have grown from about $1.8 billion in December 2017 to $60 billion as of December 2020. The rapid rise in UPI’s adoption rate was the result of seamless digital payment services offered by private players such as Google Pay and PhonePe. In fact, Alphabet (the parent company of Google) suggested to the U.S. Federal Reserve that it consider a UPI-like architecture for digital payments. On the back of technology platforms aimed at paperless governance such as UPI; Aadhaar; paperless KYC (know your customer), the process of electronically verifying the credentials of a customer); and DigiLocker (which issues and verifies documents digitally), India has now built a critical set of technology stacks and platform use cases that could help with large-scale interventions involving all segments of society.

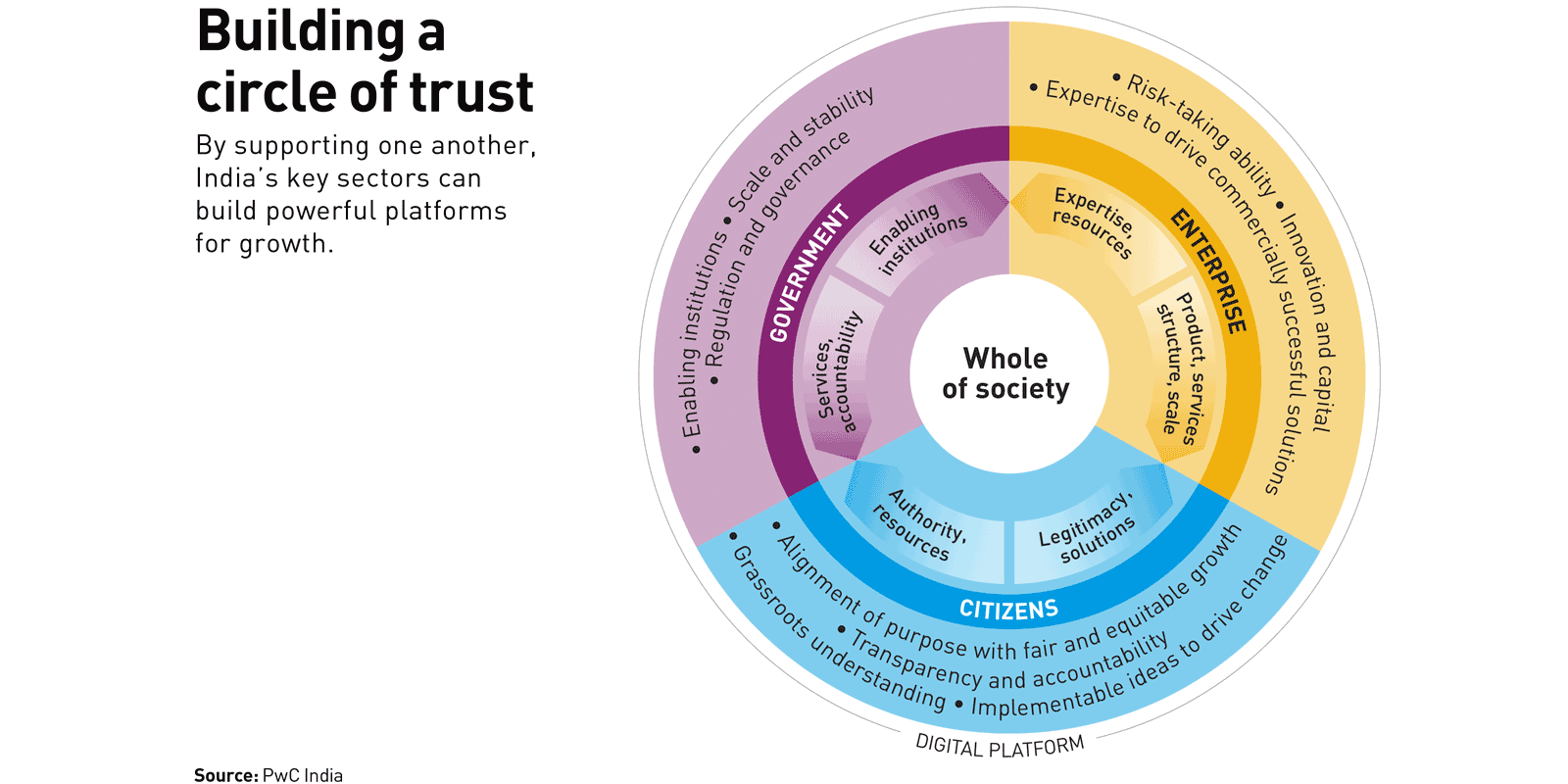

But pursuing a high level of growth across the whole economy requires taking the concept of platforms a step further. A shared vision of full-potential growth can be achieved only by adopting what we term a whole-of-society platform approach. This requires a partnership involving the private sector, civil society, and the public sector across metropolises and urban, semi-urban, and rural districts. Unless each segment of society brings forth its best attributes and resources, it will be difficult to ensure a rapid and inclusive recovery. The whole-of-society platform approach entails creating a circle of trust around enterprise, government, and citizens (see “Building a circle of trust”).

The core of the platform approach suggests that beyond short-term stimulus, government resources and medium-term investments should be directed toward enabling infrastructure that can expand the envelope of economic activity. This will enable citizens and the private sector to contribute to the recovery. Investments in such enabling platforms tap into the republican energies of this large democracy and create powerful platforms on which the economy can be built, without stretching the government’s scarce resources. The energies and expertise of enterprises and citizens support revival and growth, rather than depending on government largesse.

The groundwork laid by the government over the past five to seven years to create a stack of digital platforms is enabling a rapid transition. Nearly every Indian now carries a digitally authenticated Aadhaar identification number that is connected with a mobile number. This serves as the foundation for the 2014 Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana bank accounts, a government financial inclusion program that aims to expand affordable access to financial services such as savings accounts, remittances, credit, insurance, and pensions. India now has more than 400 million such bank accounts. During the first phase of the pandemic, they enabled the transfer of $5.2 billion in cash benefits, as part of the fiscal stimulus, to citizens via digitally authenticated and secured platforms.

India is investing and further building on platform solutions. These include what is known as the JAM trinity — for Jan Dhan accounts that enable financial inclusion, the Aadhaar card, and a mobile number — and the DISHA Dashboard, which draws data from 42 flagship government plans into a single place. The government’s adoption of digitization for delivering services to citizens has further accelerated with initiatives such as the Aarogya Setu app (a mobile application to keep people informed of their potential risk of COVID-19 infection), iGOT (integrated government online training of civil servants), and the National Digital Health Blueprint — all of which were rolled out during the pandemic. This platform-based approach is meant to tap into high digital potential, stimulate private innovation, and enable collaboration between the public and private sectors at sharply lower cost.

For many years, India has been learning the hard way that entrepreneurship, investment, and economic growth suffer when savings are held, credit granted, and payments settled outside the formal system, to the benefit of usurious intermediaries. As a result, India's government plans to deploy its digital stack and platform-based approach to bring more of the population into the country’s formal financial system and to retain individuals in the system, enlisting them as indispensable parts of the growth engine.

Such platforms will also ensure that those beyond the small minority who are already thriving and connected to the best the global economy has to offer are afforded the same access. To build an inclusive revival, India will have to ensure that all of the country’s urban, semi-urban, and rural cities and towns are joined to the modern world. To date, many of these cities have remained cut off from India’s growth model largely due to a lack of physical and digital connection and enabling infrastructure. To be sure, some significant progress has been made. More than 200,000 kilometers of rural roads were constructed between 2014 and 2019, and 99.93 percent of households have electricity. Today, several of India’s smaller cities are at the same economic level as that of the metropolises two decades back. Growth in these areas was already underway before the pandemic. Three cities in Kerala state — Malappuram, Kozhikode, and Kollam — were the only Indian cities listed in the top 10 of the world’s fastest-growing cities in a survey conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit in January 2020.

A history of resilience

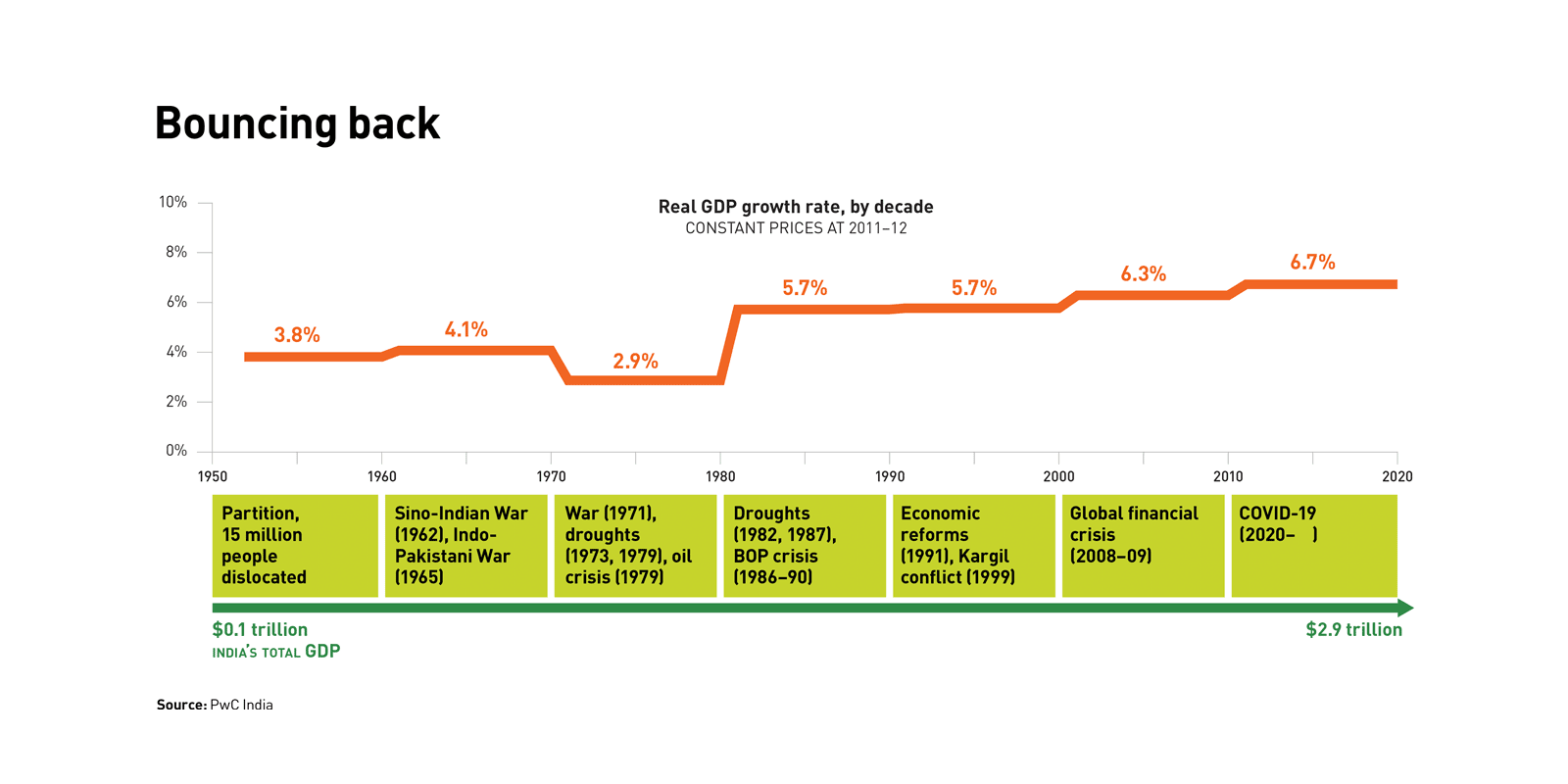

Since gaining independence in 1947, India has weathered a series of shocks to the system.

In the decades of the 1990s and 2000s, India had a reasonable growth run that consolidated and strengthened its political processes, often overcoming wars and drought. Exogenous economic shocks — such as the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the Kargil conflict in 1999, the dot-com bubble in 2001, and the global financial crisis in 2008–09 — hampered progress. But each time the country made a speedy recovery and resumed its growth trajectory. Over the 73-year period ending in 2020, India managed 5 percent compounded annual growth, a remarkable record that brought GDP to US$2.9 trillion. And 2020 represented the first recession since 1980.

A global exemplar

The road toward achieving the goal of meeting India’s full potential is anything but straightforward; it contains bumps, potholes, and curves. A full-potential mindset must factor in the need to reconfigure systems for long-term success and sustainability. Executing on the strategy outlined in our report requires careful planning and intense collaboration between organizations. But it offers immense possibility.

India’s efforts also offer lessons to other emerging democracies. Its response is another step in the country’s economic maturity, which has been growing since it gained independence in 1947. Like many other emerging countries, India, at its outset, found that its institutions were burdened by the damage caused by an extractive colonial rule, and set a course of socialistic redistribution of wealth and resources. The 1991 reforms opened the economy in metropolitan India with a sentiment of “your growth can also spur mine,” guided by a market economy. Although this approach triggered faster growth, the growth was not widely distributed.

COVID-19 is a trigger that can make the sentiment of mutual growth mainstream by deepening and widening the market economy. When a larger proportion of citizens are brought into the production and consumption process, using technology and platforms, everyone can benefit. Recovery will be faster and more inclusive, and can be designed to be environmentally sustainable from inception. In areas such as health, education, and government, these growth elements can be innately digital and feature enhanced productivity and sustainability. Full-potential revival growth can be a trigger to move from extractive or antagonistic economic structures for which emerging economies are infamous to a whole-of-society approach for revival and growth.

The ancient Indian teacher and philosopher Chanakya articulated this in Arthashastra, a Sanskrit treatise on statecraft and economic policy written approximately 2,300 years ago: The purpose of enterprise is not only to create wealth but also to manage environmental impact while regulating public conduct so as not to hurt others. Today that tenet assumes significance beyond India, for the world at large.

India holds out the hope of putting forward its best thinking and energy to address these challenges and create products, goods, and services for its own 1.35 billion citizens as well as for other citizens of the world. If India can successfully ease its frictions, we may see more global growth that is both rapid and inclusive.

- Shashank Tripathi is the leader of government strategy, transformation, and aerospace and defense for PwC in India. Based in Mumbai, he is a partner with PwC India.

- Kushal Sinha advises clients in the energy, utilities, and resources sector for Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting practice. Based in New Delhi, he is a director with PwC India.

- Vishnupriya Sengupta works on leadership communications for PwC India’s advisory line of service and leads research and insights. Based in Kolkata, she is a director with PwC India.