How to succeed in uncertain times

In a difficult environment, leaders need to resist the impulse to adopt a defensive pose. They must instead take actions that will position their organization for success.

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of strategy+business.

Uncertainty is like the weather. It’s always there, part of the atmosphere, and a condition over which individuals and organizations have very little control. The severity of uncertainty, like the severity of the weather, can rise and fall. At the moment, around the world, CEOs are operating under a series of severe uncertainty alerts.

There is great uncertainty surrounding the geopolitical context in which companies operate: the continuing saga of Brexit; trade tensions between the U.S. and China; tensions in the Middle East and Eastern Europe; and large-scale demonstrations against the status quo in Chile, Lebanon, and Iran. There is structural uncertainty — namely, the disruption to many business models brought about by technological change, the rapidly changing nature of work, climate change, and tectonic shifts in consumer needs and tastes. Consider, for example, how auto companies are beginning to retool their operations and supply chains to focus more on electric drivetrains and less on the internal combustion engine. Regulatory uncertainty, another omnipresent factor, is also at a high, as businesses grapple with shifting patterns of regulations such as tariffs, evolving data privacy regimes, structural shifts in tax policy and the regulation of technology transfers, and international investment.

More than 10 years into the current global expansion, there are widespread worries over growth itself. Over the past 12 months, the International Monetary Fund cut its forecast for 2019 global growth from 3.7 percent to 3.0 percent. Few forecasters predict a global recession — there have been only two years in the last 75 (1944 and 2009) in which the global economy didn’t grow. But in PwC’s 23rd Annual Global CEO Survey, some 53 percent of CEOs said they thought the economic growth rate would be lower in the following 12 months than in the past 12 months — up from only 5 percent saying that just two years ago. What’s more, there are no signs that the clouds of uncertainty will dissipate if a few outstanding issues are resolved. Few people are under the illusion that a decisive move on Brexit, or the repeal of some of the tariffs that China and the U.S. have levied on each other, will lead to smooth sailing.

Leaders — being humans — are wired such that they have difficulty coping with uncertainty. When these different sources of uncertainty occur at once, exacerbating one another, the level of general emotional uncertainty rises. People tend to forecast by extrapolating recent experience endlessly into the future. Once it becomes uncertain whether expected growth will materialize, people can easily become unmoored. When they receive information that muddles the view, they tend to react in predictable ways that are not always constructive. Economist Herbert Simon won the Nobel Prize for his work on what he called “bounded rationality,” pushing back against the conventional wisdom that leaders are rational decision makers. Instead, he argued, they use judgment shortcuts, called heuristics — rules of thumb that simplify things — to make decisions.

Consider the heuristics that appear during periods of heightened uncertainty. Leaders reflexively reduce investment, freeze hiring, slash marketing and brand investments, avoid entering new markets, and sometimes stop making decisions altogether. Such defensive moves are entirely understandable. And in previous periods of uncertainty, they may have been necessary for survival. But they can be counterproductive in the short term, and even more so in the long term. Acting in a procyclical manner — pulling in the reins when things are already slowing down — has the effect of aggravating the situation (as John Maynard Keynes’s paradox of thrift holds, when households and companies cut spending amid a recession or in its aftermath, it reduces demand and makes everybody poorer). Worse, it leaves companies poorly positioned to benefit from the next stage of the cycle, when things start to improve.

How should leaders manage in the face of uncertainty? The good news is that we know, from theory and practice, the right approach and mind-set to adapt. Sailors navigating tricky winds, shifting tides, and mercurial weather systems prepare their vessels so they can sail on safely and purposefully, and companies can do the same. Rather than simply reacting instinctively and responding to the informational noise detected by their instruments, leaders can move swiftly and proactively to alter their course and chart a new one — and capitalize on dislocations in the market.

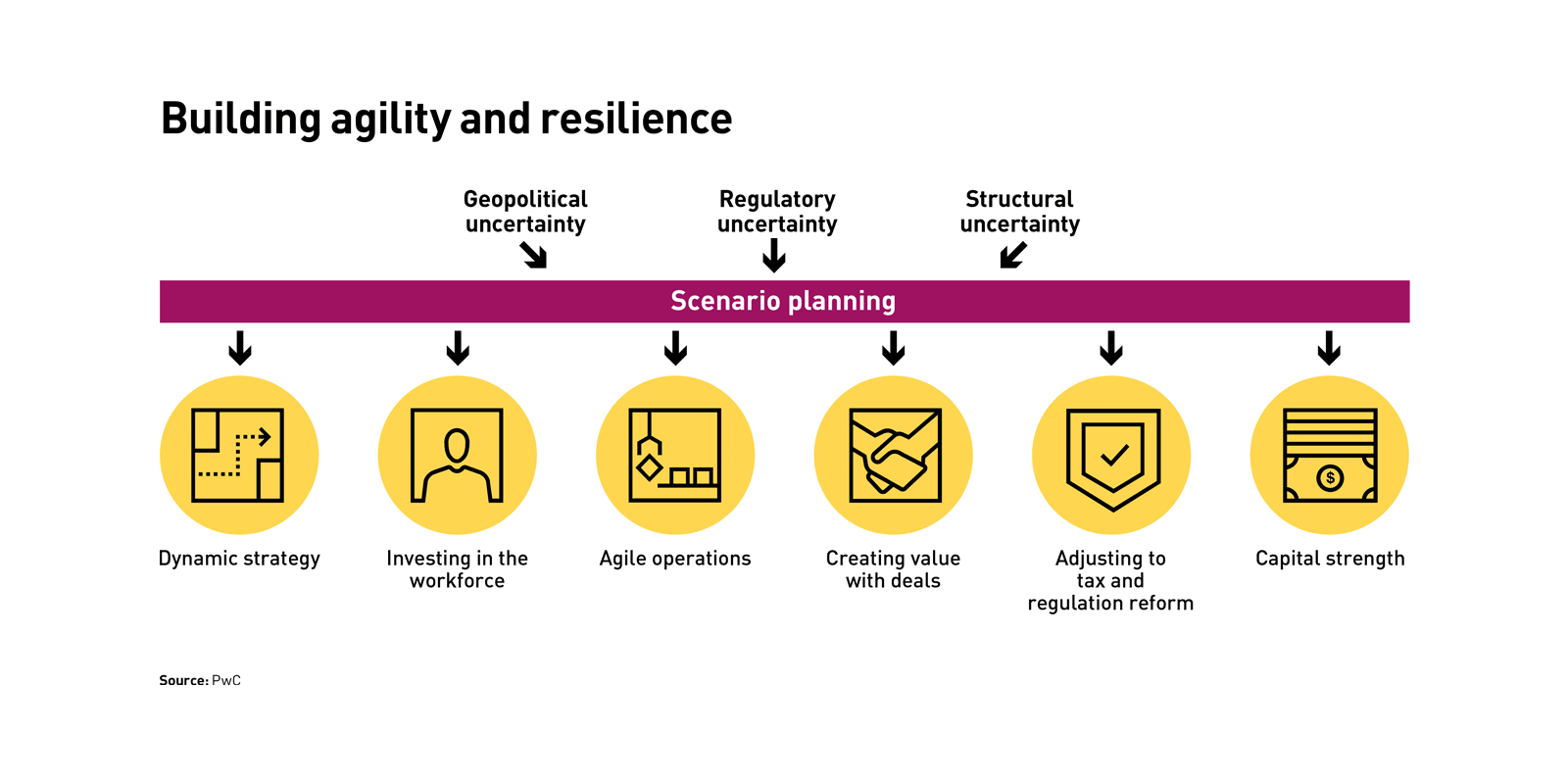

The interlinked and mutually reinforcing attributes required to succeed in uncertainty are clear. Whether the topic is strategy or workforce, operations or deals, tax and regulation or finance, the same message applies. Organizations must have a bias toward action. As a baseline, companies must strive to be Fit for Growth*, by aligning costs with priorities and strategy, investing in differentiated capabilities, and using traditional and digital levers to execute. Rather than setting on a single fixed course, they must continually engage in scenario planning, constructing and evaluating an array of options that offer a broader view of the landscape and possibilities for success. They must build the capacity to be agile — possessing the balance and capability that enable them to shift focus, priorities, and resources to meet changing circumstances. And they must evolve to become more resilient — able to withstand strong external forces, quickly recover from setbacks, and stay in a position to benefit from new opportunities (see “Building agility and resilience”).

Dynamic strategy

It all starts with moving to craft strategy in a new way. Strategy has historically been a linear enterprise: define a future vision, a way to play, and differentiating capabilities, and then put investments behind them. But when the environment is highly uncertain, it is difficult to have clarity on the path forward. The great challenge of managing amid uncertainty is that the potential outcomes are much more numerous than is typically expected — for the economy at large, and for the behavior of competitors and consumers. That means that leaders need to be as clear about what they will not do as they are about the initiatives they will pursue. In order to be more resilient to change, as our colleagues Sundar Subramanian and Anand Rao have written, strategic decision making has to become more dynamic and probabilistic. Defining strategy, then testing and tweaking it to adjust to internal and external changes, is critical to building a competitive advantage.

Technology and data play a crucial role in building a strategy that is agile, resilient, and dynamic. Big data and machine learning allow for a greater ability to model economic, corporate, and human behavior. Defining a set of plausible futures and constructing a digital twin of the operating environment can create a picture of how different drivers of uncertainty interact with one another. Teams can thus consider a wide range of scenarios — not just what will happen if the economy grows at 2 percent or 3 percent, but what will happen if a market in one country crashes while another booms, or if a leading competitor introduces new products at a lower price point or goes into bankruptcy.

After implementing pilots to test selected moves in the real world and identifying the reinforcing factors and dynamics that drive differentiation, companies can focus their efforts on building out and scaling the capabilities that enable them to grow or reinforce competitive advantage. Continually monitoring performance provides real-time feedback. As the environment changes — as is typical in times of heightened uncertainty — the process of market sensing and testing begins again. Pursuing such a path creates a much greater sense of optionality, prescribing the sets of capabilities and investments worth pursuing under different contingencies. Running multiple scenarios on how a company can succeed under different sets of conditions increases confidence. It also leads to the generation of an array of actions and capabilities (so-called no-regret options) that are good candidates to invest in immediately, regardless of the cycle and level of uncertainty.

Investing in the workforce

In times of uncertainty, it is common for companies to reduce head count, put hiring freezes in place, and leave positions open. Although this may make sense, and it is always vital that the workforce be sized for the purpose of an organization, simply freezing activity means companies can miss out on filling critical needs and areas. As companies contemplate a wider range of options and scenarios, they must ensure that their workforce has the new skills required by the new digital world. Investing in efforts to make the existing workforce more agile and resilient to changes in the environment can boost an organization’s capacity to thrive in uncertain times.

Companies should recognize the potential of longtime employees. In many instances, the work and tasks they do can be taken over by machines. But their experience and capacity to learn are valuable assets. When budgets don’t allow for adding new head count, it is even more vital to develop people so they can adjust to and fill the organization’s evolving needs. It is more efficient and often more cost-effective to move people across the organization than it is to cut in one place and recruit elsewhere. As part of its Upskilling 2025 program, for example, Amazon is investing US$700 million over six years to help current employees gain the skills that will enable them to move into technical roles in areas such as machine learning, software engineering, and IT support.

Organizations need to be proactive in other ways to construct options for their human capital strategy. They can take advantage of dislocation in labor markets to attract people with needed skills. And whether they rely on new or existing hires, companies can build resilience by making their workforce more flexible. Given advances in technology, changing expectations, and the growth of the infrastructure supporting independent work, some chunk of the workforce prefers to work on a contingent basis. That means companies are able both to access needed talent and skills and to position themselves as a partner/employer of choice. More significantly, when the outlook is less clear, rather than cut back or release people, organizations can flex down and rebalance their use of contingent workers.

Leaders must also recognize that periods of heightened uncertainty can take a toll on workplace culture. When team members are concerned about the future of the organization, some may choose to leave for other opportunities, and others may become fearful and less engaged. Leaders, as they seek to build their workers’ skills for the future, must double down on consistent and positive communications that emphasize steps the organization is taking to be more agile and resilient.

Supporting the workforce with agile operations

It’s not enough just to identify different scenarios and invest in building a workforce that can weather uncertainty. Companies can act on the options they generate only if their operations can support the execution. In times of uncertainty, it is imperative for organizations to focus on operational agility. Doing so prepares people to make the quick pivots that can be the key to surviving and thriving.

In some ways it is harder to rethink an operational strategy than it is to rethink a commercial strategy. In the pre-digital era, the operational reconfiguration following a strategic reshaping — e.g., shifting production and supply chains feeding the U.S. market from China to Mexico — sometimes took years. The challenge, and opportunity, for operations now is to use new technologies such as digitization, AI, or robotic process automation to reshape operations rapidly so that they can mirror the constantly shifting commercial landscape.

At root this approach means understanding which operations and capabilities give an organization a competitive advantage, and making sure the company owns them and invests in them. It is important not to lose control while cutting costs. Manufacturers and service providers should identify good costs — the technologies that provide solutions, differentiate the business, and are difficult to copy — and invest in those. Outsourcing is a key component of building an agile operation. But in times of uncertainty, companies that outsource should take special care to both capture value and prevent value from leaking. Companies should not outsource functions they have yet to optimize themselves.

Create value with deals

Uncertainty tends to paralyze deal making or to push companies into transactions that are defensive and reactive. Companies naturally pull back on inorganic growth, and the risk tolerance of boards, management, and investment committees — as well as shareholders — declines. But companies that are sufficiently agile to execute transactions when they can, rather than when they have to, will find that deals present occasions to boost growth and pull ahead of rivals. Because more motivated sellers appear in uncertain times, companies can potentially take advantage of deal flow from organizations that are divesting assets. It is no surprise that private equity firms tend to do their best deals and create the most value by buying at the trough of a cycle, when both multiples and profits are depressed.

In evaluating deal opportunities, organizations should draw from the Fit for Growth mentality, focusing on acquiring technologies, operations, and units that bolster desired capabilities and enhance the core business. The corollary, of course, is that divestment strategies should center on selling noncore assets that free up resources for investment. Even if they lack clarity on the short-term prospects surrounding any one business or unit, companies can shape their future by focusing on the long-term structural trends about which they have some level of certainty — for example, the continuing evolution of e-commerce, or a move to a lower-carbon energy system. Companies that invest now, regardless of economic conditions, may be best suited to ride the next technological wave.

Agile deal makers develop plans that permit them to move quickly to create value. In times of uncertainty, traditional 100-day windows for rolling out a value creation plan narrow. In this era of dynamic strategy, successful acquirers and investors can use analytics and modeling to work on integration and other core value creation levers while they are conducting due diligence. That way, those levers can be implemented instantly.

Moving quickly is essential in times of uncertainty not just because of shifting market dynamics, but because delays can have a negative impact on two crucial components that underlie the success of deals: culture and talent. Culture takes a long time to develop and a great deal of effort to maintain, yet it can fall apart in a relatively short time. Failing to plan for cultural change will undermine the value created in a merged organization. Meanwhile, talent is increasingly at the forefront of deals, which are often motivated by the desire to gain access to intellectual property and specific skills. Acquirers can reduce uncertainty by identifying crucial employees before an acquisition and incentivizing them to remain. After the deal, aggressively and clearly communicating value creation plans will help retain key personnel and build buy-in from them.

Adjusting to tax and regulation reform

One of the biggest drivers of the current uncertainty is the truly complex landscape of tax and regulation reform. In a range of large industries — technology, energy, resources, financial services, transportation, trade — the regulatory situation is volatile and prone to significant change. Many organizations have found that these shifts impact their industry, the specific markets in which they operate, and the general environment for business. Unfortunately, hiding under a rock is not a suitable option. In order to be resilient to shifts in the tax and regulatory environment, companies must get ahead of the changes and, where appropriate, work with industry peers and government to improve outcomes.

No one action, by itself, can dispel a heavy cloud of uncertainty. But if organizations can get out of their defensive crouch and assume a more aggressive stance, they have a better chance of maintaining their balance and shaping their future.

In some instances, changes in the regulatory environment can fundamentally alter the business model. Automotive manufacturers, for example, are having to evolve their operations ahead of continually changing standards for emissions, pollution levels, and safety. Those that have been most forward-thinking in doing so will find they are most resilient to the changing environment. In other instances, regulatory and tax shifts may lead to a rethinking of existing practices and an opportunity to further align operating models with regulatory, legal, and fiscal policy.

Embracing technological solutions can help companies manage compliance issues while they assess the longer-term impact of other changes. Understanding how to find and assemble the data required for new regulatory disclosures — on elements as varied as supply chains, the source of ingredients, and energy use — will allow companies to meet requirements while enhancing their reputation. Above all, being in a position to respond effectively will enable a business to continue focusing on its trading environment and not be further disrupted by legal or regulatory challenges at an already difficult time.

Capital strength

Companies can implement capabilities-driven strategies, invest in human capital, and execute deals effectively only if they rest on a strong financial foundation. But finance has its own heuristics in a time of uncertainty. Commercial organizations are often slow to react to changes to their forecasts. Working capital often increases, consuming more cash and effectively restricting liquidity. And companies often become motivated sellers at a time when asset prices are low. To ensure effective action, it is vital not just for finance to act as an operationally involved partner and conscience of the business, but for all key operational functions, including commercial, procurement, and supply chain, to be actively engaged.

By harnessing data and information technologies to run scenarios involving their business, companies can review and challenge economic, business, and sales projections — and continually feed the results into updated forecasts.

Companies should review and challenge the normal models that operational process owners use to run the everyday business. This means reviewing lead time assumptions and seeking ways to shorten them. Finance professionals should ensure that safety stock calculations still reflect the current situation, and identify the parts of the portfolio or large customers for which it is worth investing in inventory. Finance needs to keep a close eye on customer payment performance to monitor early warning signs. To build flexibility in periods of heightened uncertainty, companies should proactively fine-tune working capital and reduce the level of receivables before customers run into their own liquidity challenges.

Act now

No one action, by itself, can dispel a heavy cloud of uncertainty or significantly mitigate its impact. But if organizations can get out of their defensive crouch and assume a more aggressive stance, they have a better chance of maintaining their balance and shaping their future. Building and harnessing the mutually reinforcing attributes of optionality, agility, and resilience will enable leaders to adopt the strategies and mind-sets that allow them to succeed in the full spectrum of uncertain outcomes. Pursuing this path takes a lot of courage. Companies must consciously lean into changes and counterintuitive activities in the precise moments when it is most uncomfortable to do so, or when the forces of inertia and gravity are pushing them toward a predictable outcome.

Seeking out sources of assurance, relying on data, and building trust among stakeholders can serve as important sources of ballast and support. In times of uncertainty, all stakeholders — employees, investors, customers, and suppliers — make more intense demands for information. They constantly seek data and perspectives that can help them build their own resilient and dynamic personal and professional strategies. In such moments, the heuristic may be to reduce the flow of information — precisely because leaders feel less uncertainty about what they should say, or have less confidence in the accuracy of a projection or forecast. Here, too, thinking counterintuitively is beneficial. Opening up channels of communication will strengthen the bonds linking stakeholders and expand the view of what is possible. Rather than being an excuse to detach or check out, uncertainty should be a spur to engage and build sustainable advantage.

Author profiles:

- Will Jackson-Moore leads PwC’s global private equity, real assets, and sovereign investment funds practice. Based in London, he is a partner with PwC UK.

- Heather Swanston leads PwC’s global business recovery practice. Based in Tokyo, she is a partner with PwC Japan.

- Mohamed Kande is vice chairman of PwC US and also the global advisory leader. His expertise spans the areas of operational strategy, technology development, mergers and acquisitions, and operations management.

- The authors would also like to thank the following colleagues for their contributions to this article: Peter Bartels, a partner with PwC Germany; Vinay Couto, a principal with PwC US; Duncan Cox, a partner with PwC UK; Alexis Crow, a managing director with PwC US; Paul Leinwand, a principal with PwC US; Andrew MacGilp, a partner with PwC UK; Anna Maltby, a senior manager with PwC UK; Neil McBride, a partner with PwC UK; Andrew McPherson, a partner with PwC Australia; Curt Moldenhauer, a partner with PwC US; Robert Pethick, a principal with PwC US; Alastair Rimmer, a partner with PwC UK; and Daniel Windaus, a partner with PwC UK.

- *Fit for Growth is a trademark of PwC registered in the United States.