Mastering the connection between strategy and culture

Business leaders often are tempted to focus on strategy over culture. But the strongest companies take four key actions that deliver the best of both.

A version of this article appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of strategy+business.

Ahmed Galal Ismail was impressed by the level of employee engagement in Majid al Futtaim Properties, the owner of the Mall of the Emirates—a huge shopping complex in Dubai that even boasts an indoor ski slope—when he started as CEO in late 2018. And he had big plans. Ismail wanted to build a company that delivered extraordinary customer experiences using its physical properties and digital platforms. He needed people who had the capabilities to anticipate customer expectations, rather than sit back and wait for customers to engage.

Working closely with the human capital director, he set about developing a “market shaper” culture—an organization perceived as driving the evolution of the sector—to stimulate more innovation and external orientation. At town halls with staff, he said he saw culture as a driver of transformation, and strengthening the corporate culture was one of his five Day One transformation initiatives, alongside reinforcing the core business, mastering efficiency, retuning the real estate development engine, and accelerating data-driven transformation.

The COVID-19 pandemic tested, but didn’t break, the strength of the connection Ismail was building between strategy and culture. It was straightforward to make the most urgent decisions, which were to preserve cash and to communicate more frequently with employees and stakeholders. Strategic decisions required more deliberation, given their complexity and materiality, and considering the uncertainty of the longer-term effects of the pandemic. Ismail also wanted to ensure that the steps he had taken to develop a culture that supported a mutually beneficial ecosystem with his tenants would survive. Freezing rents was a critical strategic decision that signaled this commitment. His efforts worked, and business at the mall bounced back in 2021 to beat pre-pandemic levels.

A fresh imperative to act

Like Ismail, other leaders currently face making decisions about where they choose to play and how to win (their corporate strategy) as well as how to encourage their employees to make—and shape—that journey with them (their organizational culture) at a time of considerable change. Customers have moved further online, and competitors’ positions have shifted. Some, like the platforms, have strengthened; others have weakened or disappeared. At the same time, organizational cultures need to evolve to enable a new hybrid of virtual and physical working arrangements, and to recognize higher expectations of a better work–life balance.

In this context, it might be tempting to focus on developing strategy more than culture, or vice versa—the latter if you believe “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” a quote misattributed to Peter Drucker (it seems it was actually said by a hospital CEO). Focusing exclusively on either strategy or culture would be a mistake. A strategy that describes a “big picture” vision without specifying what it requires of the organization’s culture is destined to fail, especially if it doesn’t build from existing strengths. Likewise, evolving a culture without recourse to a clear, compelling strategic direction risks wasting effort, if not disruption; improving engagement, well-being, and productivity helps only if you’re serving the needs of your current and future customers in a way that others can’t or won’t.

The goal should be to master the connectivity between strategy and culture. They both should be anchored by capabilities—the “key activities in which you must invest disproportionately and perform distinctively to underpin your theory of competitive advantage,” according to author and CEO advisor Roger Martin. Prioritizing and investing in key capabilities must be supported by management systems and resources. In other words, the connection between strategy and culture has to be embedded in the management system and the allocation of resources, because together these support the decisions to invest in the critical few behaviors that disproportionately drive performance. Examples of capabilities include understanding customers (as in the case of Majid al Futtaim), partnering with suppliers, and building strong brands.

At the heart of this endeavor is an appreciation and incorporation of the perspectives, mindsets, and skill sets of others. Every organization faces a unique set of challenges and context. There are strategic moments in an organization’s journey that have a disproportionate impact on outcomes. Getting them right creates a multiplier effect on other activities as people learn new ways of working and increase their advocacy for the program of work. Terence Mauri, founder of Hack Future Lab, a network of technology industry leaders, calls these “imprintable” moments. They include:

• Strategy development. If you want your culture’s defining traits to be inclusivity, empowerment, and collaboration, the strategy process must reflect this desire. Opening up strategy development to participation, away from the typical top-down, closed approach, is a crucial act. It might involve running “dream sessions” in which employees envision the future of the company or contests designed to encourage participation and co-creation from customers, suppliers, and partners.

• Negotiations with important third parties (such as suppliers, partners, and agencies). If you want to encourage more curiosity as a cultural trait, negotiations should involve sufficient time spent understanding the interests of the parties involved and exploring a range of options for mutual gain.

• Recruitment of key talent. The messages imparted to recruits in the selection and onboarding process should reflect the strategic priorities (as communicated to the candidates), while the interviewers (and others involved) should demonstrate the desired traits and behaviors.

• Critical conversations with employees. There are important moments with employees—if they are new to the organization, underperforming, ambitious, or looking for a change in roles—in which it’s vital to discuss and clarify strategic priorities and expectations for performance and behavior.

• Crisis performance. In crisis situations, be honest about the scale of the problems, transparent about how long it will likely take to recover, clear about the actions you want people to take, and positive about opportunities ahead in line with the strategy. People remember the words and sentiments of leaders in times of crisis far more than in other moments.

• Launch of new services, products, or experiences. A launch is one of the most high-profile actions in the eyes of customers, let alone employees. It should exemplify the strategic direction of the business and showcase the culture the organization is looking to evolve.

• Performance review. Creating the structures that incentivize performance in line with the organization's strategy requires careful design, consultation, and implementation. Short-term, individualistic performance measures will rarely enable a strategy founded on collaboration.

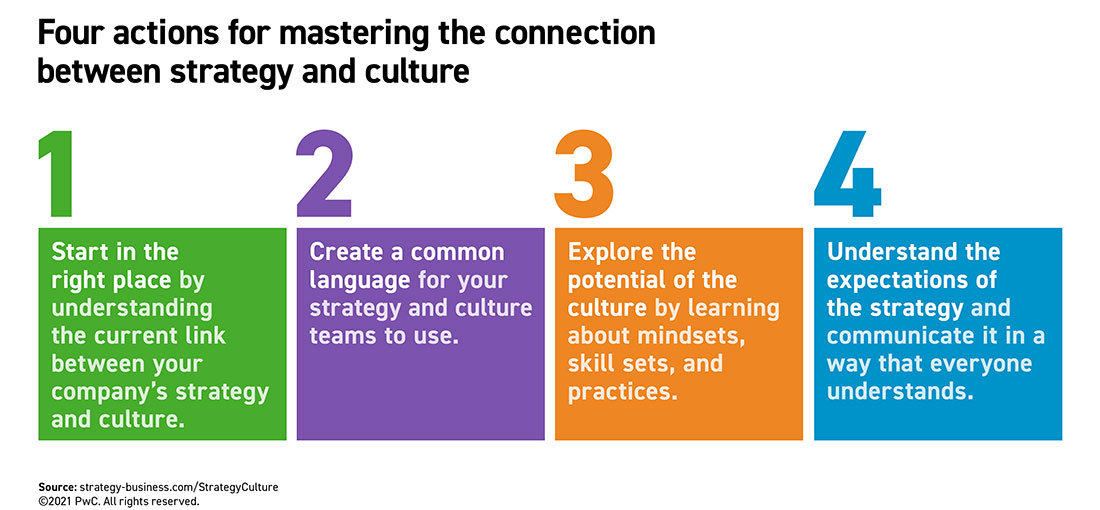

Managing to focus on each of the imprintable moments individually should not be that difficult. Focusing on all of them consistently and coherently is much harder, yet it is critical if you want to embed new organizational norms and behaviors that support the strategic intent. Below are four actions that leaders need to take to help navigate that journey successfully.

Start in the right place

Ideally, you develop strategy and organizational culture together in a connected, integrated approach from the beginning. You experiment, learn, and iterate as you align your strategic direction with the behaviors that will help you get there. Indeed, in a recent online poll I conducted with 300 executives, 56% said that they used this approach; 30% said strategy came first.

Sometimes it is necessary to put more emphasis on one aspect before connecting the two. A toxic workplace, an ethical issue, or a poor relationship with a supplier may require paying immediate attention to culture, especially if important stakeholders, such as investors or regulators, express their concerns. This requires interrogating the causes, taking remedial action, dealing with the immediate impacts, and starting to build new ways of thinking and working. In this scenario, developing a new strategy might need to wait until there is sufficient cultural progress.

At other times, the strength of competitor activity (e.g., in launching new products or services, or in pursuing aggressive pricing policies) or the dynamics of customer behavior may require a company to make strategic choices before working on the evolution of the culture.

If you’re taking on a leadership role, ask the following questions about your organization’s context:

• Given what is happening in our business now, do we have the capacity to adopt an integrated approach?

• If we’re facing difficulties, to what extent do they relate to strategy or culture?

• What are the most important decisions we can make to fix the issue, or at least create some momentum?

• What are the implications of delaying work on strategy or culture, and how material are they?

Create a common language

The work involved in developing strategy is often undertaken by people whose roles, backgrounds, and styles differ from those of the people involved in evolving culture. Typically, the HR team leads on culture, while the strategy or marketing team leads on strategy. And the teams work independently of each other, which results in a lack of coherence, a loss of ideas, and a reduction in buy-in.

There are strategic moments in an organization’s journey that have a disproportionate impact on outcomes. Getting them right creates a multiplier effect on other activities.

To improve on this pattern, connect and combine specialists in culture and strategy, whether in an integrated team or in coordinated work streams. The strategy people should share emerging hypotheses, possibilities, and choices, while the culture people call out the strengths, limitations, and problems of the existing culture. They both should be complemented by what Jon Katzenbach of the Katzenbach Center at Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business, calls the authentic informal leaders (AILs) who champion the evolution of the culture, from their position of influence across the organization (see “Strategy and culture,” below). AILs also become trusted advisors in the strategy process, model future behaviors, and advocate for the strategy.

This is the approach used by Lindström Group, a leading European textiles rental company based in Finland, in the development of its 2025 strategy. The strategy team, led by Kati Järvi, worked with HR to enable both teams to renew their leadership principles, which played to the strengths of its culture (“we care”) and their aspirations for its development (“we dare”) in order to support the execution of their strategy.

Connecting strategy teams and HR teams is a good start, but it’s not enough. It’s necessary to create a common language for them to use, as advocated by Charles H. Kepner and Hirotsugu Iikubo in their book Managing Beyond the Ordinary. Develop a glossary of terms and concepts that are integral to the approach. Start at the basics of what we mean by strategy and culture and move to specific terms, such as values, traits, and behaviors (in culture), and advantage, value proposition, business model, and capabilities (in strategy). Include terms that apply to both, such as weak signals of change, a term coined by Rita McGrath, a management professor at Columbia Business School. A weak signal of change is the first indicator of an emerging issue that may become significant in the future, whether outside the organization (e.g., customer behaviors, regulatory interventions, technology developments) or inside (e.g., employee sentiment).

If you’re embarking on an effort to link strategy and culture, ask yourself:

• Who are the people we need to assemble to drive this work forward, and how well do they represent the skill sets, backgrounds, and constituents in the organization?

• What are the most important terms and concepts, and have we defined and illustrated them?

• How much effort are we putting into upskilling people to master the frameworks we’ve selected to develop strategy and culture?

Strategy and culture

As the Katzenbach Center’s Jon Katzenbach tells us, culture is a multidimensional collection of self-sustaining behaviors, traits, feelings, and beliefs—many of which are informal and emotional—that determine how work gets done. Captured well, corporate culture paints a picture of what an organization is capable of doing. This informs the development of strategic possibilities, including considerations of where to compete, what vehicle to use (e.g., organic development, partnerships, ecosystems, or acquisitions), and how long it will take (e.g., to upskill, acquire talent, or change working practices) to get there. It also helps determine how strategy should be conceived and developed within the organization—how best to encourage participation, surface new ideas, challenge orthodoxy, test emerging hypotheses, and execute the plan.

Likewise, strategy is a collection of choices about what an organization needs to do to win, satisfying the needs of customers, employees, and investors. This informs the design of the portfolio of businesses to own and operate; the capabilities they need to build; and the resources, systems, and culture that support these activities.

Explore the potential of the culture

If you’re looking to drive complementarity between strategy and culture, it’s important to develop an in-depth understanding of what they need from each other to do their respective jobs well. As you develop strategy, learn how the culture really works. At its best, organizational culture can be the source of strategic differentiation and a key ingredient of the value proposition to customers; 81% of the 3,200 PwC 2021 Global Culture Survey respondents agreed. Understand what people talk about, criticize, admire, remember, and appreciate in your organization, and capture the stories, tonality, and language as you do.

Hidden beneath these sentiments are the often unwritten norms and values that characterize the culture, and the most important enablers for the successful execution of a strategy, such as tone from the top; technology and tools; and incentives, compensation, and benefits—the top three such enablers, according to the PwC survey. One senior executive I worked with kept a journal of these aspects that she used as a prompt before an important meeting or presentation in the early days of her role.

At the same time, explore how weaknesses in a culture—in particular, mindsets, assumptions, and practices—limit the exploration of new possibilities and, ultimately, superior performance and higher levels of growth. For example, a strategy that involves pursuing new geographic or product market opportunities might be a big stretch if the culture is risk-averse and internally focused.

At the beginning of the process to develop its 2025 strategy, the Lindström team that was composed of both HR and strategic leaders recognized the power of the company’s emphasis on responsibility or sustainability in the organizational DNA. They also anticipated big changes in climate and ethics that would affect their business and their customers’ businesses significantly. Connecting these two leadership teams made it easier to formulate their strategic choices—for example, to enable their employees to help their customers become more sustainable by providing materials that were sustainably sourced.

Consider these questions to help clarify what culture means to your business:

• When we’ve been at our best, what have we done, and what have others said about us?

• What drives these behaviors and actions?

• What sustains the traits and behaviors we want to nurture and evolve?

• What are the assumptions that we make about who we are, and how we work, that hold us back?

• How can we overcome inertia, laziness, procrastination, and other limiting human traits?

Understand the expectations of the strategy

If you’re looking to evolve the culture and encourage participation, you’ll need to understand the need for a new strategy, as well as the expectations leaders have for what it will deliver. This requires a clear articulation of the potential opportunities to pursue as well as the problems facing the organization. Communicate the strategy in a way that people understand and relate to, so they can try to embed it in their day-to-day actions. Share stories and anecdotes to visualize what the organization will look like when it implements the strategy. Use moments in history that illustrate the courage, resilience, and ability of the organization to move in new directions. This builds a sense of pride; taps into “muscle memory”; and engages people at a deeper, more personal and emotional level.

As you develop strategy, consider these questions:

• What are the compelling reasons for making a change in the direction of the organization, and why make it now? What might happen if we continued with our current trajectory?

• What weak signals of change in customer sentiment, competitor activity, or internal performance should people be aware of?

• What are the most exciting opportunities ahead, and why is this organization best placed to pursue them?

• What are our differentiated capabilities, and what are we doing to invest in them?

The implications of the pandemic—new hybrid work practices and strategic decision-making in complex and uncertain environments—represent an opportunity, if not a requirement, to master the connection between strategy and culture. There is also an increased risk of failure if culture and strategy are developed out of sync. To address the opportunity effectively, start by piquing your curiosity about the interactions between the two; creating a common language; learning about the mindset, skill set, and practices of the aspects you are less familiar with; and creating a set of expectations that everyone understands.

Author profile:

- David Lancefield is a strategist and coach who has advised more than 35 CEOs and has led 15 digital transformations. He is a contributing editor of strategy+business, and he also hosts the interview series Lancefield on the Line and publishes the newsletter Flashes+Sparks.