Strategy or Culture: Which Is More Important?

Although culture is much more than an “enabler” of strategy, it’s no substitute for it.

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” These words, often attributed to Peter Drucker, are frequently quoted by people who see culture at the heart of all great companies. Those same folks like to cite the likes of Southwest Airlines, Nordstrom, and Zappos, whose leaders point to their companies’ cultures as the secret of their success.

The argument goes something like this: “Strategy is on paper whereas culture determines how things get done. Anyone can come up with a fancy strategy, but it’s much harder to build a winning culture. Moreover, a brilliant strategy without a great culture is ‘all hat and no cattle,’ while a company with a winning culture can succeed even if its strategy is mediocre. Plus, it’s much easier to change strategy than culture.” The argument’s inevitable conclusion is that strategy is mere ham and eggs for culture.

But this misses a big opportunity to enhance the power of both culture and strategy. As I see it, the two most fundamental strategy questions are:

1. For the company, what businesses should you be in?

2. And for each of those businesses, what value proposition should you go to market with?

A company’s specific cultural strengths must be central to answering that first question. For example, high-margin, premium-product companies that serve wealthy customers do not belong in businesses where penny-pinching is a source of great pride and celebrated behavior. Southwest has chosen not to enter a NetJets-like business, and that’s a sound decision.

Likewise, companies whose identity and worth are based on discovery and innovation do not belong in low-margin, price-competitive businesses. For example, pharmaceutical companies that traditionally compete by discovering novel, patentable drugs and therapies will struggle to add value to businesses competing in generics. The cultural requirements are just too different. This is why universal banks struggle to win in both commercial and investment banking. Whatever synergies they might enjoy (for instance, from common customers and complementary capital needs) are more than offset by the cultural chasm between these two businesses: the value commercial bankers put on containing risk and knowing the customer, versus the value investment bankers have for taking risk and selling innovative financial products.

Maintaining cultural coherence across a company’s portfolio should be an essential factor when determining a corporate strategy. No culture, however strong, can overcome poor choices when it comes to corporate strategy. For example, GE has one of the most productive cultures in the world, and its former leader, Jack Welch, concedes that his acquisition of Kidder Peabody was a failure because its cultural needs did not fit GE’s cultural strengths. The impact of culture on a company’s success is only as good as its strategy is sound.

No culture, however strong, can overcome poor choices when it comes to corporate strategy.

Culture also looms large in answering the second question above. In most businesses, customers consider more than concrete features and benefits when choosing between alternative providers; they also consider “the intangibles.” In fact, these often become the tiebreaker when tangible differences are difficult to discern. For example, most wealthy individuals choose financial advisors more for their personal chemistry or connections than their particular range of mutual funds. Virgin Airlines tries to attract passengers who like its offbeat, non-establishment attitude in how it operates. Culture experts are right to point out Southwest, Nordstrom, and Zappos because these companies have instilled norms of behavior that are essential features of their winning value propositions: from offering consistently low-price, high-quality service in Southwest’s case, to consistently delivering surprising staff service at Nordstrom and leading customer satisfaction at Zappos. What these companies really demonstrate is how culture is an essential variable—much like your product offering, pricing policy, and distribution channels—that should be considered when choosing strategies for your individual businesses. This is especially so when the behavior of your people, and particularly your frontline staff, can give you an edge with your customers.

Strategy must be rooted in the cultural strengths you have and the cultural needs of your businesses. If culture is hard to change, which it is, then strategy is too. Both take years to build; both take years to change. This is one of the many reasons that established companies struggle with big disruptions in their markets. For example, all the major credit card companies are seeking to transition from traditional payments to digital commerce. This shift in strategy will be difficult to pull off. It not only requires a cultural change, but also a change in companies’ target customer, value propositions, and essential capabilities—the three most fundamental choices a business strategy comprises!

Consigning strategy to just a morning meal for culture does injustice to both. Confining culture to the narrow role of “enabling” strategy prevents it from strengthening strategy by being part of it. It also weakens the power of strategy to turn your company’s cultural strengths into a source of enduring advantage.

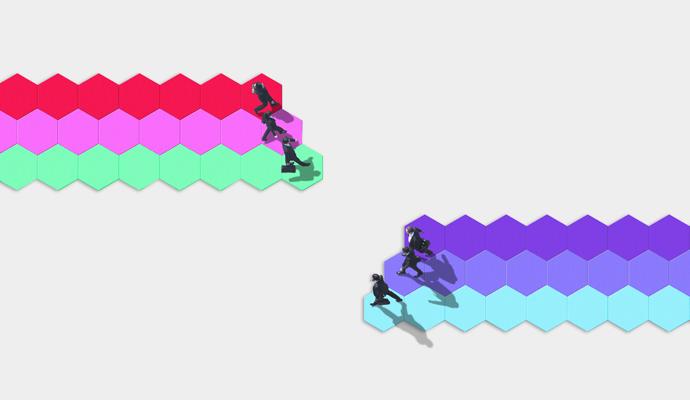

Don’t let culture eat strategy for breakfast. Have them feed each other.