“Like mountain air in the veins”

H.G. Wells’s 1908 satire, Tono-Bungay, about a fictional health tonic, provides valuable insights into the entrepreneurial mind and spirit.

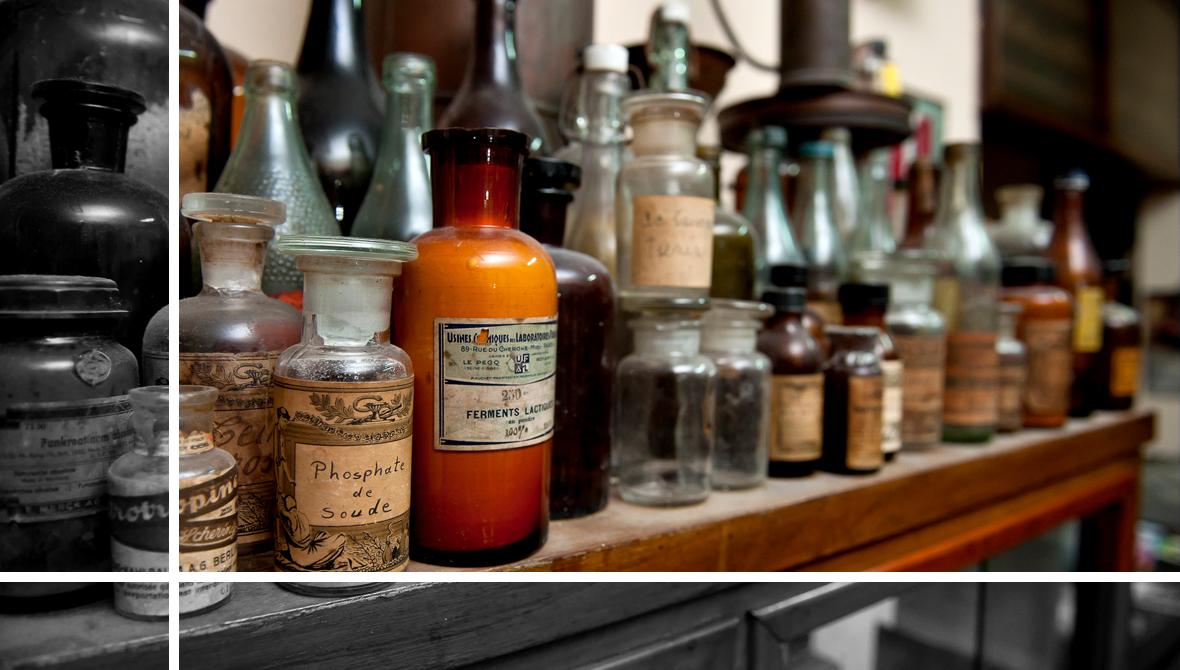

It’s easy to sneer at the past. Long ago, when physicians labored largely in ignorance, people placed faith in patent medicines, though their effectiveness was unconfirmed and their contents were typically unknown. By now, of course, science has come a long way, and drugs that have been tested and proven effective save people’s lives.

Yet we also have a US$4.4 trillion global wellness industry that encompasses all kinds of potions and practices, many of them far-from-proven remedies for discontents that may have little to do with the body. Entrepreneurs have long understood the enormous potential market for this sort of thing, and the crucial importance of advertising in making dubious wellness products fly off the shelves. Baby boomers will recall the many TV commercials for Geritol, which promised to address “tired blood.”

Fans of H.G. Wells (1866–1946) would not have been surprised. Remembered mostly for his science-fiction works, including The War of the Worlds, the English writer’s vast interests encompassed technology, advertising, finance, and social psychology. He poured this knowledge and more into an eerily prescient novel that is both a mordant critique of business and one of the best books ever written about an entrepreneur. The book, like the fraudulent elixir at its center, is entitled Tono-Bungay. Those seeking laughter as well as business insights will find it an effective tonic.

First published in 1908, Tono-Bungay is set largely in the booming Britain of the Victorian era, when a vast empire feeds the growing factories of the home country with raw materials, and the owners of new business fortunes must be accommodated by an entrenched aristocracy. The tale is narrated by young George Ponderevo, who by a stroke of fortune finds himself sent to live with his Uncle Edward, a small-town pharmacist. “Oh! one rubs along,” Edward says of his little business, in which he’s forever experimenting with schemes to boost sales. “But there’s no Development—no Growth. They just come along here and buy pills when they want ’em.... They’ve got to be ill before there’s a prescription. That sort they are.”

We soon learn what sort Edward is. Certain, after a brief period of misguided study, that he’s figured out the pattern of share prices, he loses everything through reckless stock speculation—including his nephew’s inheritance, which had been accumulated painfully from his mother’s wages as a servant in a country house. Edward and his witty spouse, George’s Aunt Susan, bear up to the disaster bravely, moving to London after selling the shop—and passing George along to the new owners with the rest of the inventory.

But they have seen something in one another, Edward and George, and before long, the latter receives a summons from the former. Like the character in The Graduate who offers young Benjamin a single incantatory word of guidance (plastics), Uncle Edward reveals the basis of his reunion with his nephew: Tono-Bongay, a tonic he’s concocted that he’s sure will work wonders for their finances. (Wells was inspired here by the success of Coca-Cola, created by an Atlanta druggist in 1886.)

A classic entrepreneur, ever attuned to trends and ready to take a risk, Edward knows that he doesn’t have the attention span or organizational skills to build a business. That is why he recruits his scientifically minded nephew to do the job for him. George recognizes Tono-Bungay for a scam, but he is motivated by the chance to earn. He’s fallen in love, and he believes —however disastrously—that success in business will enable him to marry. Both men work “infernally hard,” and in no time, George rationalizes operations, installing something like an assembly line. He also channels his uncle’s creative genius into an ever-widening advertising campaign. Some of the ads warn against dubious competing nostrums. Others press home with a trio of hard questions: “Are you bored with your Business? Are you bored with your Dinner? Are you bored with your Wife?” The answer, inevitably, is Tono-Bungay, “Like Mountain Air in the Veins.”

To both George and his Aunt Susan, Edward’s restless grandiosity is transparent. Yet they both find him irresistible, and Wells’s portrait of him is surely among the greatest of any entrepreneur in English literature. Edward is what we might today call a change agent, an absolutely instinctive disrupter.

Wells’s portrait of Edward is surely among the greatest of any entrepreneur in English literature. He is what we might today call a change agent, an absolutely instinctive disrupter.

“He was always imaginative, erratic, inconsistent, recklessly inexact, and his inundation of wealth merely gave him scope for these qualities,” his nephew recalls. “It is true, indeed, that towards the climax he became intensely irritable at times and impatient of contradiction, but that, I think, was rather the gnawing uneasiness of sanity than any mental disturbance.”

Poets and painters have nothing on Edward when it comes to creativity, for innovations of all kinds are bubbling up in him day and night—some plausible and others, well, less so. As a druggist, he offers customers the chance to pay a monthly fee in exchange for free medicines whenever they get a cold. Later, once rich, he contemplates a megalomaniacal scheme to inundate much of the Holy Land. It’s a “marvelous” idea, he tells George. “Suppose we take that up…and run that water sluice from the Mediterranean into the Dead Sea Valley—think of the difference it will make! All the desert blooming like a rose, Jericho lost forever, all the Holy Places under water…. Very likely destroy Christianity.”

Tono-Bungay is a scathing satire in which all commerce is nothing more than a fraudulent effort to fund pointless status-seeking, symbolized by the extravagant mansion Edward sets out to build. Such a novel might well have been a didactic screed. Instead, it’s a penetrating delight—and a powerful cautionary tale, for it’s clear from the start that Edward and George’s manic enterprise is doomed.

For one thing, George’s heart isn’t really in it; once he’s built Tono-Bungay and its offshoots into a success, he becomes increasingly caught up in aeronautical experiments, much as some of today’s greatest tycoons have become obsessed with space travel. Still, nobody knows better than George that absent the business ventures of men like Edward, Britain would remain a hopelessly class-bound nation of a few hereditary masters and a vast army of servants.

Edward’s entrepreneurial energies, married to his nephew’s management skills, can produce great wealth and new opportunities. But in the realm of finance, Edward’s same instincts, unfettered by ethics or good sense, lead to spiraling risk and complexity as eager investors throw ever more money at Britain’s new business genius—who is not immune to the public’s delusions about his talents. His empire proves to be a house of cards, and in a bid to save the situation, his nephew embarks on a mad scheme to steal a radioactive substance from a remote island. (Wells was as cynical about imperialism as he was about business.) In the effort, George compromises himself in far worse fashion than he’s ever done at home.

At heart, Tono-Bungay is about a fraud, but note carefully that nothing good comes of it. The real lessons here for business readers are twofold. First, without integrity, you are doomed, and second, success will force you to face the problem of purpose. It’s clear from Tono-Bungay that the best way to address both is to think about your values in advance, before it’s too late. You can’t buy a tonic to do the job for you.