Revisiting Atlas Shrugged

The iconic novel, which celebrates risk-taking and self-interest, has important lessons for current debates surrounding inequality and liberty.

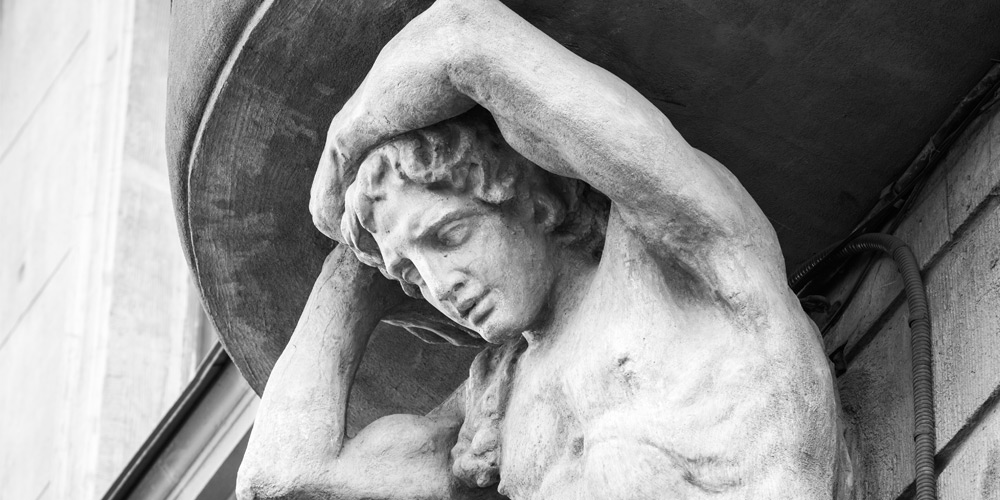

Do you imagine yourself an Atlas in your business life, holding up the heavens? Does the world seem ungrateful? What if you got together with your fellow Atlases and just shrugged the whole thing off?

You can if you like. But, really, it’s never very useful to imagine yourself a god when in fact hardly anybody is indispensable. And if there is no key-person insurance on your life, you probably aren’t in that small category. I’m certainly not, despite the feelings of martyrdom I indulged while trudging through Atlas Shrugged on your behalf.

Sooner or later, a regular column on business and literature must face up to the 1,100-page gorilla of the genre and deal with libertarian icon Ayn Rand’s strange and furious magnum opus. This is a novel, after all, that venerates risk-taking executives and innovators as heroes. Whatever its literary shortcomings, there’s no denying its cultural impact.

A 1991 survey for the Library of Congress and the Book-of-the-Month Club asked Americans which books had most influenced their lives. Atlas Shrugged came in second — after the Bible. In 2012, the Library solicited suggestions for an exhibition on books that shaped America. The public’s top choice? Atlas Shrugged. Sixty-three years after it was first published, the book still sells.

Atlas Shrugged is of course much reviled among the bien-pensants, partly for being a terrible book but mostly for exalting an ethos of unabashed self-interest. In its Manichean world view, people come in two basic varieties: producers and looters. Why, then, does the book excite such enduring interest in readers — particularly in young readers — year after year?

A cynic might say that selfishness never goes out of style. But it would be fairer to observe that the novel’s message of self-reliance and success without guilt appeals to a certain class of high performers across the generations — and may hit home with all the more force in our own therapeutic and hypersensitive age. At a time when success is often dismissed as “privilege,” Rand tells achievers they have earned it.

People prone to reading 1,100-page novels about business may also be especially susceptible to the book’s defense of rationalism, which is made by characters who aren’t bloodless robots but passionate human beings. Exhibit A would be the novel’s brainy and disciplined protagonist, Dagny Taggart.

During the book’s decades in print, the appetite for stories about strong women has only increased. The heroine of Atlas Shrugged is just such a woman, a confident executive who disdains fools and slackers and considers her sexuality a gift that should never be sacrificed to convention. Taggart, an engineer, is as prone to pride and love and sympathy as anyone else. But overall, her head rules, along with her principles, and she runs a railroad without sentimentality — or timidity.

Last but not least, readers may have an enduring appetite for a novel about business that isn’t premised on the evils of capitalism. In Atlas Shrugged, on the contrary, Rand’s moral exemplars are women and men of business for whom doing well and doing good are perfectly aligned because they are one and the same. Getting rich through innovation and commerce, honorably conducted, is an unalloyed virtue.

Atlas Shrugged is set in New York and elsewhere in the United States at an indeterminate time. (Given the focus on mining, metal-making and, especially, railroads, it is probably the 1950s.) The overall tone is portentous, and despite the massive length, there is something highly schematic and even slapdash about it. The melodramatic plot is convoluted, but boils down to this: The most capable people in business, persecuted by government and hemmed in by crony capitalism, quietly absent themselves as part of a talent strike under the leadership of a mysterious figure named John Galt.

“We are on strike against martyrdom,” the messianic Galt explains, “and against the moral code that demands it. We are on strike against those who believe that one man must exist for the sake of another. We are on strike against the morality of cannibals, be it practiced in body or in spirit. We will not deal with men on any terms but ours — and our terms are a moral code which holds that man is an end in himself and not the means to any end of others.”

Many of the book’s literary shortcomings fall under the category of excessive length; what might have been an Emersonian parable about freedom, dignity, and fulfillment is all but trampled by the author’s unbridled verbosity. There are many better novels about business, and there is little to be gained by dwelling on the cartoonish plot and characters of this one.

There is good reason, on the other hand, to consider the lean parable at the heart of this fat book, and to ask what we can learn from it about the inequality that has become a large and still growing issue worldwide. It’s an issue that business leaders ignore at their peril.

In Atlas Shrugged, Rand had one important insight: In the modern world, liberty and inequality will tend to grow or shrivel in tandem. As everyone in business knows, human abilities differ, a fact made obvious when people and their talents are relatively unfettered. As a result, it will be challenging for free societies to limit inequality without also constraining freedom. That challenge is magnified by technology, which allows the most talented to have the widest possible impact and reap the greatest share of rewards.

In the face of such developments, Atlas Shrugged seems relevant not just as a cautionary tale about collusion and creeping socialism, but as a useful caricature of a self-dramatizing elite — one so swollen with wealth and self-importance that it tries to bring the entire country to heel by withholding the magic of its energy and intelligence.

Atlas Shrugged seems relevant not just as a cautionary tale about collusion and creeping socialism, but as a useful caricature of a self-dramatizing elite.

Ayn Rand was born Alissa Zinovievna Rosenbaum in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1905, and her outlook was shaped by her family’s flight from the Russian Revolution. This formative horror of collectivism probably accounts for her failure to appreciate something wise executives and entrepreneurs know: that if freedom produces inequality, freedom can only persist in a democracy if its greatest beneficiaries voluntarily embrace a very old-fashioned ethic — one of personal propriety and public service firmly anchored in country and community.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the clairvoyant 19th-century Frenchman whose Democracy in America is such an uncanny guide to the national character, said that the United States was marked by a “legitimate passion for equality that spurs all men to wish to be strong and esteemed. This passion tends to elevate the lesser to the rank of the greater.” But he also warned of “a depraved taste for equality which impels the weak to want to bring the strong down to their level and which reduces men to preferring equality in servitude to inequality in freedom.”

Societies need the talents and leadership of their most capable citizens. But it’s dangerous for these gifted individuals to develop a messianic complex, just as it’s dangerous for the rest of us to erect guillotines outside their houses.