Tales of the original Industrial Revolution

Elizabeth Gaskell’s Victorian-era novel North and South has a great deal to teach us about the enduring tensions between progress and prosperity, industry and labor, and rural and urban life.

Elizabeth Cleghorn Stevenson came into the world on September 29, 1810, in circumstances that will seem almost inconceivable today. Born in what is now a part of London, she was her parents’ eighth and final child, but one of only two to survive to adulthood. When she was 13 months old, her mother died. In 1827, her last remaining sibling was lost at sea.

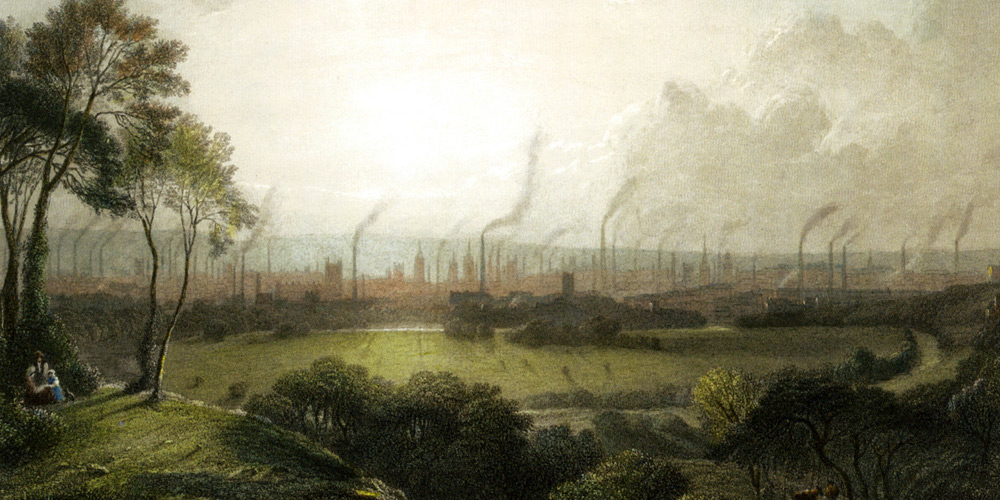

Yet in the context of her times, she was fortunate: She was raised by a loving aunt in surroundings of pastoral refinement, blessed with energy and intelligence, and given an education. On a visit to grimy Manchester as a young woman, she met the Unitarian minister William Gaskell, with whom she would enter into a successful marriage. By joining her life to his, she traded the bucolic comity of her youth for the filthy crucible of the Industrial Revolution. Of the Gaskells’ seven children, four survived. Elizabeth herself — Mrs. Gaskell, to her legions of admirers — only made it to 55.

And this was progress! Today, thanks to the affluence and invention fostered by a century or two of industrial transformation, most of us in the West can expect to live much longer, and to be spared the sorrow of burying our offspring. Gaskell’s losses give us some sense of how hard life must have been during the transformation, but it is her writing, which she began after the loss of a child, that makes the era’s social upheaval come alive.

Other authors have written vividly of Victorian life — not for nothing do we have the word Dickensian, after all. But few novels tackle the social, moral, and economic complexities of the period with as much clarity as Gaskell’s North and South, first published serially in 1854–55 by Dickens himself.

Experienced readers of novels that deal with business may be surprised to find that this one neither indicts capitalism nor vilifies its practitioners. On the contrary, Gaskell is sensitive to all parties caught in the brutal but productive free enterprise of 19th-century Britain. What is even more striking about this most readable of Victorian novels is that the dilemmas of the author’s time are so tenaciously still with us.

Just consider the book’s title, which refers to the divide between the unhurried, rural South of England in Gaskell’s day and the bustling, industrializing North. It’s a divide that persists, on an entirely different basis to be sure, in the England of today, to say nothing of the world at large.

The book’s premise embodies another such enduring issue: the movement of people from country to city. In this case, 18-year-old Margaret Hale and her family are torn from their lives of threadbare gentility — and service to others — in the idyllic Cornish village of Helstone when her father is driven by religious dissent to resign his post as the local parson. And so the family moves to Milton, a thriving manufacturing city (and a stand-in for Gaskell’s own Manchester), where the former vicar is hired to tutor one of the city’s new textile barons.

Some contrasts were immediately apparent: “‘A private tutor!’ said Margaret, looking scornful: ‘What in the world do manufacturers want with the classics, or literature, or the accomplishments of a gentleman?’

“‘Oh,’ said her father, ‘some of them really seem to be fine fellows, conscious of their own deficiencies, which is more than many a man at Oxford is.’”

The uprooted Hales do not adjust easily to their new way of life. In Helstone, unlike Milton, people lived in familiar social arrangements, knew and cared for one another, and were in touch with nature. The air was clean, the pace unhurried. “In such towns in the south of England, Margaret had seen the shopmen, when not employed in their business, lounging a little at their doors, enjoying the fresh air, and the look up and down the street. Here, if they had any leisure from customers, they made themselves business in the shop — even, Margaret fancied, to the unnecessary unrolling and rerolling of ribbons.”

The baggage Margaret brings to her new home includes the antibusiness prejudices of her social class. “I don’t like shoppy people,” she says of some acquaintances in trade. “I think we are far better off, knowing only cottagers and labourers, and people without pretence.” She adds, without self-consciousness: “I like all people whose occupations have to do with land; I like soldiers and sailors, and the three learned professions, as they call them.” She’s talking here of the ministry, medicine, and law. “I’m sure you don’t want me to admire butchers and bakers, and candlestick-makers, do you, Mamma?”

Yet in Milton, Margaret befriends the Higgins family, whose troubles embody those of the working classes — and whose patriarch becomes a ringleader in a strike that shuts down the mills. Margaret’s sympathies are with the strikers, but she’s also made the acquaintance of her father’s bootstrapping pupil, the charismatic and morally inflexible John Thornton — perhaps the city’s most prominent mill owner. Even as he learns from her father, he teaches Margaret the ways of free enterprise.

Thornton is unwaveringly ethical, by his lights. But his focus on liberty, his natural gifts, and his dangerous confidence combine to leave him blind to the sufferings of his employees; he righteously considers them free and equal counterparties in a labor transaction. What Thornton doesn’t see is that people who are hungry or feeling exploited aren’t likely to adhere to the same principles — or hold them in the first place.

But he’s no robot, and neither is Margaret. They have too much personal chemistry for that, and over the course of the book they grow, even if, much of the time, they seem to grow apart. Gaskell is amply endowed with novelistic gifts; she is a brilliant social observer, a subtle psychologist, and a skilled sentimentalist. But she’s also fully attuned to the moral, political, and social problems of modern capitalism as it emerges from a world of feudal obligation and familiarity.

So though the book is certainly a love story — for what was a novel in the 19th century without romance? — its larger subjects are authority and justice. What are the proper rights of capital owners? What protections should be given to labor? To what extent does anyone’s station in life reflect either good fortune or personal application? What do life’s winners owe its losers?

As John Thornton will soon learn, nobody’s authority is absolute — something business leaders today must understand if they are to survive. Other aspects of North and South resonate with equal force. Milton, for example, exists in a pall of fossil-fuel pollution, belching into the atmosphere the greenhouse gasses that will ultimately warm the planet. Like many of today’s most dynamic cities, the place is riven by inequality.

Wages, then as now, are an excruciatingly sticky matter; Milton’s hands simply won’t stand for cuts, even if trade is deteriorating. Rising wages make automation more attractive. And there is friction over immigration. During the strike, Thornton brings in Irish laborers to reopen the mill. Even the poles of today's political leanings are apparent; Margaret is a redistributionist liberal, while Thornton is a free-market conservative.

“We hate to have laws made for us at a distance,” he says at one point. “We wish people would allow us to right ourselves, instead of continually meddling, with their imperfect legislation. We stand up for self-government, and oppose centralisation.”

But things are more complicated than they seem. Milton’s workers are at once downtrodden and liberated, and it becomes clear that the revolution underway isn’t just industrial. The Hales, hoping to hire a servant, discover it’s not easy finding “any one in a manufacturing town who did not prefer the better wages and greater independence of working in a mill.” In interviewing potential hires, their loyal retainer, Mrs. Dixon, is surprised that these women weren’t shy about “questioning her back again; having doubts and fears of their own, as to the solvency of a family who lived in a house of thirty pounds a-year, and yet gave themselves airs, and kept two servants.”

Things are more complicated than they seem. The workers are at once downtrodden and liberated, and it becomes clear that the revolution underway isn’t just industrial.

Replete with tragedy and misunderstanding, North and South is nonetheless suffused with hope. After the disastrous strike, Higgins and Thornton discover they are more alike than they realized, and begin to grope toward a way forward. But Thornton’s eventual victory over labor proves Pyrrhic, and his business collapses — in part due to his own high-minded unwillingness to speculate with his creditors’ cash. The pain of this catastrophe deepens his desire to improve the lot of workers — even as he remains humble about the ability of any business owner to do so. He’s still a conservative, in other words, even if now a compassionate one.

Ultimately, in North and South, the meek quite literally inherit the earth. A legacy — that classic deus ex machina of Victorian literature — turns Margaret into John’s landlord, giving her the chance to get our chastened businessman back on his feet. Can the proud entrepreneur accept? Can labor and capital embrace one another? Can Margaret and John? These questions are in doubt until the very last pages, and you will turn all of them to get there. Mrs. Gaskell, it seems, was a pretty shrewd businesswoman herself.