The long nose of augmented reality

The AR market is predicted to top more than US$1 trillion by 2030. So where’s the killer app that will win over consumers?

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of strategy+business.

Every five years or so, I contemplate cutting my hair into a fringe. Experience should have taught me by now that this is always a bad idea, but nevertheless, I live in hope that perhaps this time, I’ll really look like a French model.

The last time I wanted to make a bad decision about my hair, L’Oréal hadn’t yet put out its Web-based augmented reality (AR) app that would allow me, in theory, to try out “countless” hairstyles and colors, just by uploading a picture of myself and applying a filter-style overlay. L’Oréal’s app was released in 2018, and although “countless” was a bit of an overstatement — there are 56 — I now know approximately what I’d look like in a bad wig. I'm no closer to deciding about the fringe.

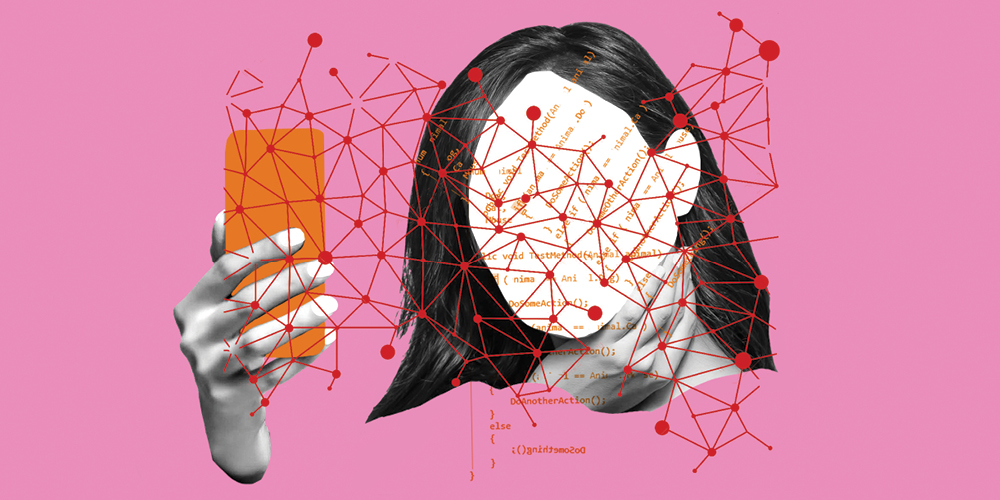

It’s perhaps not fair to complain about the failures of AR just because this one app can’t definitively tell me if I will look like French model. I mostly buy into the bright future predicted by experts — but this isn’t the only unsatisfying experience I’ve had. The novelty of placing a subtly glowing armchair with a Swedish name in your living room wears off quickly; “trying on” sunglasses gets stale as soon as it’s clear that neither they nor you look quite the same in real life. Even the most impressive AR apps I’ve seen, such as the YouCam Makeup app, which uses facial mapping technology to give you a virtual experience of what your makeup choices might look like, are only marginally more exciting than a Snapchat filter. Most people who play Pokémon Go — my Pokémon-obsessed children among them — don’t bother with the AR function. Why would they? It sucks battery life and doesn’t materially add to the experience of catching them all.

In its current incarnation, AR is, frankly, disappointing. It’s at best a solution to problems that aren’t really problems, and at worst, insufficient in meeting what could be actual needs (like my fringe question). So why am I sure that AR is still going to be the next big thing? Because it will be a really useful idea — when we get it right.

In its current incarnation, AR is, frankly, disappointing. It’s at best a solution to problems that aren’t really problems, and at worst, insufficient in meeting what could be actual needs.

Humans think in multiple dimensions and senses; technology is already enhancing and capitalizing on this, and AR is a natural extension of that. “I think the vision of having new eyes is just really compelling,” says David Rose, a technologist with the MIT Media Lab and serial entrepreneur who recently worked with glasses maker Warby Parker on its AR try-on tech.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should note that Rose is a friend. He’s also the founder of SuperSight.org, an “open innovation” lab exploring the near-term applications of AR. He is honest about the current limitations and future dangers of AR, as well as being one of its biggest cheerleaders. He agrees that the pace of AR mainstream integration has been slower than he’d imagined — “much, much slower.”

But there’s hope. “Have you ever heard of the ‘long nose of innovation’?” Rose asks. It’s the idea that behind huge technological innovations are decades of development and research made up of miniature successes and a lot of failures. Computer scientist Bill Buxton wrote in 2008 (pdf): “What the long nose tells us is that any technology that is going to have significant impact in the next 10 years is already at least 10 years old. Any technology that is going to have significant impact in the next five years is already at least 15 years old.”

For AR, a lot of that messy groundwork has already been done. AR, along with its more immersive sibling, virtual reality, has been around since the late 1960s, when computer scientist Ivan Sutherland and his colleagues (first at Harvard University, then at the University of Utah) began developing what would be the first heads-up display, a rather clunky version of today’s VR headsets. In 1965, Sutherland expressed a succinct and coherent vision of VR and AR: “A display connected to a digital computer gives us a chance to gain familiarity with concepts not realizable in the physical world. It is a looking glass into a mathematical wonderland.”

Fast forward to 2007’s introduction of the iPhone. In just a few years, almost everyone would have an unobtrusive, perpetually present link between the digital world and the physical one. In 2011, the New York Times’s tech writer, John Markoff, wrote, “Think of pointing your phone at the advertisement on the side of a bus stop and having the ad come to life, complete with interactive features.… For everyone who has seen Harry Potter and his magic newspaper, the implications are obvious.” This was it — the thing that was going to make augmented reality a real reality.

But Markoff had inadvertently hit upon the main problem with AR: the smartphone. No one wants to walk around seeing the brave new world of AR through a small handheld rectangle. Figuring out what form Sutherland’s “looking glass” should take has been hard.

“For AR to reach its potential, it must reach us in the form of glasses,” wrote Jason Cross, staff writer for Macworld, in January 2020. This is the real holy grail, a technically difficult feat as well as a design challenge. So far, no one has cracked it: Google Glass was available to the public for only about a year before it was pulled off the commercial market in 2015; ODG, an early AR glasses maker that promised “glasses for the masses,” toppled into bankruptcy in January 2019.

Back to the long nose of innovation: These failures are part of the process, not its end. Apple is rumored to be working on AR glasses, which would only be logical. Mojo Vision, a very well funded California-based company, recently announced that it has working prototypes of an AR contact lens. Bose has explored creative extensions of AR with its successful Frames, sunglasses with tiny built-in speakers for augmented audio reality. And Google Glass is enjoying a profitable and useful second life in enterprise, helping factory workers in Minnesota build agricultural machines, for example.

Applications for AR displays are finding a natural home in sports. I am genuinely lusting after Form swim goggles, which feature a heads-up display giving you real-time information on pace and lap count. And AR is mainstream, in some little, useful ways: I’ve come to rely on my car’s reversing camera and guides, seamlessly embedded in the rearview mirror.

But, according to Rose, we haven’t seen anything close to the best yet. “Humans just aren’t very good at imagining the best, imagining ideal states,” he told me. “AR could really open our eyes to see that, that idea of seeing the best world or seeing the best Linda or the best living room or the best meal. It’s closing the gap between what is and what you can imagine.”

If the long nose prediction is right, we are getting closer. I just wish the best Linda looked good in a fringe.