What Strategists Can Learn from Sartre

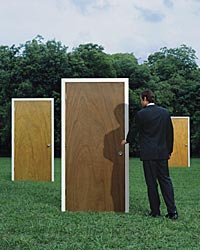

In an uncertain world where competitive advantage is insecure, setting strategy must become an existential exercise.

|

|

Photograph by Fredrik Broden |

With the help of Simmons Market Research, we had correlated different purchasing patterns with the different lifestyles. To date, VALS had been a sustained success. If suburban women between the ages of 25 and 45 driving minivans reliably and regularly chose Caffeine Free Diet Coke over Classic, whereas young males between 15 and 25 reliably went for the sugar and caffeine jolt, then the marketers at Coca-Cola would know how to spin the ads they put on MTV differently from the ads they placed on Lifetime. The theory and practice of market segmentation had been evolving for 20 years. In fact, it had been growing hand in hand with the U.S. economy as it made the transition from mass manufacturing for a mass market during the middle of the 20th century toward a more segmented market that could be described by our nine lifestyle types — nay, even, stereotypes.

On that day in May 1985, however, I realized that the VALS system was losing its predictive power. People were no longer behaving true to type. Women were shopping at Bloomingdale’s one day, Wal-Mart the next. The segment we called Achievers started behaving like Experientials. Some men were behaving like bankers by day, punkers by night. This was bad news for clients who were trying to use market segmentation to target the different stereotypes. But it was good news for the human spirit, because what this tendency amounted to was human freedom flexing her muscles. People were behaving less predictably. They were defying stereotypes.

The Unpredictable Economy

Because I had been trained as a philosopher, I immediately knew what was happening. American customers, without direct influence from the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre or Martin Heidegger, had nonetheless discovered existential freedom. They would no longer be predictable. And indeed, customers around the world have been unpredictable ever since. No general system of market segmentation or analysis has managed to capture their patterns of behavior in any reliable way.

This realization has implications that far transcend marketing, which, typically, commences once a company has identified a strategy and developed products or services for a defined customer base. For corporations, keeping up with customers who are less predictable than consumers of old requires a capacity for innovation. Where the old economy relied on mass production to meet universal needs, the new economy demands customized innovation to satisfy an endless range of wants and whims.

The old production economy was predictable because it operated in the realm of necessity; it produced goods and services people needed, and those were relatively stable. The new economy plays in the realm of freedom; it produces goods and services for a customer who is not bound by needs. The old economy called for strategies built by engineers who could calculate according to necessary laws. The new economy calls for strategies created by existentialists who understand freedom. Most important of all, the old economy operated at a regular pace, in the clockwork time of industrial production. The new economy lurches forward and backward, in some new kind of time that was anticipated, once again, by the existential philosophers.

We’re all in existential time these days. It’s not just that we’re facing a more unpredictable future; the pace and rhythm of events is also increasingly variable and unpredictable. Especially since September 11, 2001, the corporate planning horizon has widened to embrace fundamental uncertainty spanning life-or-death, boom-or-bust dimensions. This is not all bad for the human spirit — if a wider horizon reminds us of our freedom.

Just as existential philosophy emerged in Europe between the two world wars, when life got weird for individuals and the old verities no longer seemed to hold true, so existential strategy emerged during the final decades of the 20th century, as life was getting weird for organizations. Just as individuals reached for an existential philosophy that was adequate to a new sense of freedom, so corporations are now looking for the kinds of strategic tools that can accommodate real uncertainty. An existential economy, in short, demands existential strategy.

Existentialism 101

But what does that mean? For starters, existentialism is a philosophy that stresses the importance and robustness of individual choice. In a world where it sometimes seems as though there are too many choices, and too little authoritative guidance in making those choices, existentialism provides a viable approach to strategy — perhaps the only viable approach. In this article, I’d like to offer an elevator-ride introduction to the existentialist philosophy, then call out a series of specific ideas from the writings of the existentialists to show how they can help us understand our business realities and decisions on a practical day-to-day level.

In Silicon Valley, there’s a saying: “Who needs a futurist to tell us about the future? We’re building it!” This is pure existentialism. The point isn’t so much that the pace of change is increasing — Alvin Toffler’s argument in Future Shock (Amereon Ltd., 1970). Instead it’s calling into question who’s in charge — God, haphazard fate, or human invention? The existentialists have something to tell us about taking charge of our own future.

The term existentialism gains its basic meaning from its contrast with essentialism. The ancient philosophers, particularly Aristotle, understood change as biological growth. A favorite example was the acorn turning into an oak. It can’t do anything else. It is the essence of an acorn to become an oak. It cannot choose to become a maple or an elm. Its oak essence precedes its existence. First acorn, then oak.

Impose this model of growth and change on human beings and you get Plato’s theory of gold, silver, and bronze souls — souls slated, from birth, to fulfill a predetermined path. Part of the education system in Plato’s Republic involves a series of standardized national tests for separating the aristocratic guardians from the lowly worker bees. This was the first articulation of what we now know as a tracking system. You’re born bronze, silver, or gold. The tests will reveal your essence. And, as with the high-stakes exams that characterize the French system of education, once your essence is revealed, there’s very little likelihood that your existence will ever escape your class.

Such essentialism sounds downright un-American … and it is. If your essence precedes your existence, then all you can do is play out the pattern of your essence. The passage of time, to an essentialist, is like the unrolling of an Oriental rug whose every stitch, every line, every pattern was first obscured within the rolled-up rug, and then revealed as the past moved into the present.

The future, according to essentialist philosophy, is like a rug as yet unrolled: The pattern is in there; you just can’t see it yet. And as with most Oriental rugs, its pattern is probably repetitive. Prior to the focus on history and evolution by figures like Vico, Herder, Hegel, and Darwin, “the future” was seen through essentialist eyes. The very word future connoted a stretch of time that would contain more of the same, occasionally better, occasionally worse, as the eternal cycle of generation and corruption, rise and fall, repeated itself age after age.

In such tradition-bound societies, the elders know best because they know the past. Filial piety is a core value of Confucianism. Sons follow the occupations of their fathers. Tradition rules. The past rules the present. Like the pattern of the seasons or the constellations in the heavens, the basic order of the universe is not subject to biological evolution or historical change.

This sense of time and order remained sacrosanct until the works of Georg Hegel and Charles Darwin gained influence. These two writers, though very different from each other, together were the most significant sources of existential thought; only when their work was accepted was essentialism’s repetitive and cyclical image of time displaced by a linear, historical, evolutionary time that allowed for the emergence of something genuinely new under the sun.

Suddenly, humanity had a future — in the sense in which existentialists think of the future, as an open-ended, indeterminate field of untried possibilities. For existentialists, existence precedes essence. It’s not that no one or nothing has an essence. It’s just that essence, for free human beings, anyway, is achieved rather than prescribed. You become the results of the decisions you make. You don’t find yourself, as those suffering “identity crises” try to do. You make yourself by making decisions. You’re not just the result of the genes you inherited or the circumstances of your birth. Of course genes and family background make a difference, but what you choose to do with them is subject to existential freedom.

Consider the way that time is measured, and the way we normally experience it. Ever since the invention of the mechanical clock, people have conceived of time as passing in the kind of even blocks represented on Cartesian graph paper. For rocket scientists plotting a trajectory to the moon, this model of time might be the most appropriate. But as both Heidegger and Sartre noted, this kind of mathematized, regular tick, tick, tick of a mechanical clock contradicts the experience of a truly human temporality. Our minds experience time as expanding and contracting, quickening with excitement, slowing with boredom. There is a lived contrast between long durations and punctuating epiphanies. Things last a while, then they change, and there are significant choices to be made at the cusps and bifurcations.

Moments of Urgency

Such punctuations call for strategies developed prior to the moment of urgency. And as the world gets more strange, these moments will be more frequent. Scenario planning gives executives a way to rehearse different futures in the relative calm of a meeting room rather than in a “war room” set up for emergencies. Better to craft a strategy during the calm between the cusps. Once you’ve rehearsed different futures in the form of vivid scenarios, then you’re ready for the one that rolls out in fact. And even better: Once you’ve scoped out a range of alternative futures, you’re in a better position to nudge reality in a direction you’d prefer. (See “How Scenario Planning Explains Uncertainty,” at the end of this article.)

A future filled with new possibilities presents a backdrop for planning that is very different from a future that is a reshuffling of the same old same old. Reshufflings should follow laws that allow for prediction according to rules that cover every possibility. A future filled with genuinely new possibilities might not even be describable using categories and metrics that cover what has occurred before. How could a 19th-century scientist anticipate, much less predict, prime time, venture capital, gigabits-per-second, butterfly ballots, fuel cells, genetic engineering, cellular telephony, and so on?

Once you appreciate this fundamental shift in the nature of “futurity,” you are in a better position to appreciate the need for existential strategy. Once you abandon an essentialism within which the future is, in principle, predictable, and adopt an existentialism within which the future is, in principle, unpredictable, you’re bound to need a robust set of guidelines for making decisions that will be effective in any of a range of futures that might unfold.

As a philosophy, existentialism stresses that human beings have almost unlimited choice. The constraints we feel from authority, society, other people, morality, and God are powerful largely because we have internalized them — we carry the constraints around within us.

As a result, sometimes existentialists get a bad rap for preaching nihilism and meaninglessness — free fall instead of freedom. Everything is possible (they’re accused of preaching), and therefore human beings can ignore morality and duty. Thus, Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God. For Smerdyakov, the nihilist in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the death of God meant that mere anarchy was loosed upon the earth. But Nietzsche himself distinguished between a nihilism of strength and a nihilism of weakness. For the weak, the death of God means that all is permitted. For the strong, the death of God does not mean we are doomed to despair and meaninglessness. Instead, we have the opportunity to create our own lives and our own conscious sense of responsibility. Nietzsche said the only God he could worship would be a God who could dance.

This turns out to be very close to the role of managers, particularly senior executives, in large complex organizations. They don’t take on the role of God, but they do choose to define morality and its consequences for their organizations. In their classic management text In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies (Harper & Row, 1982), Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman Jr. argued that the job of the manager is “meaning making.” This challenge to make meaning in an otherwise meaningless environment is itself made to order for the existential strategist.

How, then, does one “make meaning” for an entire organization — and ensure that the choices will turn out better than if that organization simply followed in old established pathways? The existential philosophers crafted some ideas that have fairly immediate relevance to strategic practice: finitude, being-toward-death, care, thrownness, and authenticity. (See “Five Principles of Existential Strategy,” below.) Let’s explore each and its application to existential strategy.

|

Five Principles of Existential Strategy |

|

Finitude

Finitude is the existential principle closest to the conventional notion of corporate strategy, making hard decisions because you can’t do everything.

Indeed, in this mortal life, you may be able to accomplish almost anything, but you cannot do everything. There isn’t time. If you choose to be a butcher, you generally can’t simultaneously be a baker and a candlestick maker. Understanding finitude helps the existential strategist focus on the trade-offs organizations face. You can go for lowest cost or highest quality, but rarely both at once. There are choices to be made. Not all good things go together. If you’re not saying no, you’re not doing strategy. If you’re not saying no, you’re not acting strategically.

The word decision derives from the Latin for “cut off.” IBM made a strategic decision to get out of the consumer business and concentrate on services to businesses. Hewlett-Packard Company cut Agilent Technologies Inc. adrift because measuring and testing technology was not its core competence. When corporate raiders make a hostile takeover and then break up a business and sell off its parts, their reasoning often has to do with an evaluation that shows the segments are worth more on their own than as parts of a confused whole in which executives prove unable to make tough decisions.

I saw the power of finitude when working with wealthy foundations, which, like government agencies, rarely feel the risk of failure. At first glance, the job of foundation managers looks easy: Just hand out a pot of money. At closer range, the challenge is harder: how to improve the world without squandering resources or inducing dependencies that do more harm than good.

The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation in Flint, Mich., has as one of its objectives the improvement of the city of Flint — a clear goal that nonetheless leaves plenty of latitude for choices by the trustees. After spending millions in the 1980s on what was to be a destination resort called AutoWorld, they watched in horror as people somehow chose Disneyworld for their vacations instead.

In the early 1990s, the managers of the Mott Foundation engaged my colleagues and me to develop a set of scenarios showing different possible futures for Flint — a city that had been badly stung by Michael Moore’s movie Roger and Me. The upshot of the exercise was a commitment to make Flint a better place to raise children — a manageable goal that gave a new focus to the foundation’s finite grant making. Looking out for the kids was both consistent with the original deed of the gift by the Mott family and in keeping with current needs in Flint. The city had been a great place to raise a family back when rust-belt manufacturing produced a living wage. But the new economy had cut many of the old jobs, and now it would take a bold initiative to make the city a better place for kids once again.

Being-Toward-Death

If you think your life is not finite, if you think you’re immortal, then you may act as if you’ve got time for everything. If you follow the existentialists in dwelling on death, however, each day of your life will gain both preciousness and a sense of existential urgency.

The National Education Association (NEA), America’s largest labor union — thought by some to be immovable, immortal, and unchangeable — benefited from an imaginative kick in the pants from a scenario entitled “One Flight Up.” That scenario told a story in which the NEA’s building in Washington, D.C., had been sold to Sylvan Learning Systems, which leased back to the NEA a small suite of offices located “one flight up” from the main entrance. After absorbing this scenario, the president of the NEA was quoted in the New York Times as saying, “If we don’t change the way we do business, we’ll be out of business in 10 years.” This statement, his colleagues declared, would have been unthinkable a few years earlier, before he’d looked death in the face.

The union did change. Under its next president, Bob Chase, the NEA adopted “new unionism,” a strategy focused less on wages and terms of employment and more on helping its members meet the challenges they were facing in the classroom.

Asking folks to look death in the eye is not easy. Being-toward-bankruptcy is no fun. Xerox needed a vivid scenario painting a picture of a world where the copier would converge with the scanner and computer printer, and the copier business would go away. We painted such a scenario … but it wasn’t scary enough to motivate change, and their denial of death led to real bankruptcy.

BP, which once stood for British Petroleum, looked down the cellar stairs at a world “Beyond Petroleum,” the new meaning for its initials. Scenarios that mimic being-toward-death can function as a kind of anticipatory disaster relief. A near-death experience lived in imagination can draw forth the passion that exists underneath smug self-satisfaction; that kind of motivation is needed to take the actions necessary to avoid real death. It can make managers care — a relatively weak word. The German equivalent, Sorge, has more urgency to it. It means to really care, to give a damn. It means something close to passion.

Care

Heidegger focused on care as a feature that differentiates human beings from purely cognitive, Cartesian creatures. Sure, we think, we calculate, we cogitate. But we do so in a way that is different from how computers do it. My computer doesn’t give a damn. It doesn’t care. And so much the better: It is unbiased; it is unswayed by desire; it can do the wholly rational, objective calculations I want from a computer. I, on the other hand, have biases. I have desires. And so much the better again: for my desiring, my caring, gives meaning to my life. A knife is good for cutting. A computer is good for calculating. Each has a function. What am I good for? If the meaning of my life can be reduced to the kind of function that defines the essence of a knife or a computer, then my life is reduced to that of a functionary. I become a tool in someone else’s drama, a mere means to their ends, not my own.

Often organizations, especially large, long-standing ones, need a greater sense of urgency. It’s not just a matter of giving a damn about reducing time to market for new products. Sometimes a corporation must reinvent itself. Sometimes a company must break free of its past. Once upon a time Motorola made car radios. When Robert Galvin wanted to manufacture semiconductors, some of his managers thought he was nuts. But Bob Galvin, son of Motorola founder Paul Galvin, cared enough to keep his father’s legacy alive even after the car radio business declined. Later they reinvented Motorola yet again as a manufacturer of cell phones and pagers. With Bob’s son Chris retiring as chairman and CEO, the company is set to reinvent itself once again. In a world that’s gone from slow and predictable to fast and perplexing, you have to be free to reinvent yourself … or you die.

Thrownness

Of course you can’t reinvent yourself as anything whatsoever. Companies have histories. IBM doesn’t sell dog food. Sara Lee isn’t set up to manufacture computers. Heidegger called this nondeterministic conditioning Geworfenheit, or thrownness. We each landed on the earth somewhere, not nowhere. We each inherit much of who we are from our parents, our culture, or the community in which we find ourselves. Even the entrepreneur finds the second year of her new company “thrown” in a certain direction by her first year. Right-angle turns are tough. Momentum has its merits. But even for the largest corporations, straight-line extrapolation from the past into the future is a poor guide for strategic planning.

Thrownness is not just a constraint. Upside possibilities beckon the existential strategist. Aspirational scenarios showing rewarding opportunities can complement descriptive scenarios painting risks. When executives at Motorola sought our help to update their China strategy, we realized they’d been coasting on momentum. A hard look at both downside and upside scenarios led them to boost their investment, claim greater market share, and solidify their leadership position. The sheer size of the opportunities that exist in China are enough to dwarf the imaginations of planners coasting on extrapolations from the past. It takes a dancing existentialist to see such vast possibilities.

Authenticity

Authenticity is a way of being true to yourself, but the concept is tricky because, for the existentialist, being true to yourself can’t be defined as being true to your essence. Nor can it be reduced to fulfilling a function. Authenticity demands fidelity to your past, but also openness to possibilities in the future — not just one possibility (that would be a necessity), but several possibilities. Authenticity is being true to both your thrownness and your freedom. It’s making choices among possibilities and taking responsibility for your decisions.

While consulting at Motorola, I also had an opportunity to work with the company’s New Enterprises group. Their mandate was to come up with new business ideas that were close enough to Motorola’s core competencies to be plausible yet that still fell outside existing lines of business. Threading this needle is what authenticity is all about. If you try too hard to be true to your essence — your core competence — then you deny your freedom. But if you pretend you’re free to do absolutely anything — if you forget your thrownness — then you’re in free fall. Motorola’s New Enterprises group had to thread this needle, so they took a hard look at how their competence in information technology could be applied to a new and different domain: the creation, storage, and conservation of electric energy.

Neither for companies nor for individuals is the future completely indeterminate. Neither companies nor individuals are utterly free. We carry our pasts like tails we cannot lose. And that’s a relief, because we don’t want to begin each day from scratch. The skills we have learned, the competencies we have achieved, give direction and power to be used in the present as we carve the near edge of the future.

The gist of this article has moved mainly from the philosophy of existentialism toward its implications for corporate strategic planning. Here at the end, it’s worth reflecting on the resonance that resounds from the soundness of existential strategy in the corporate world and its implications for the people who then learn about existential time from the practice of scenario planning and existential strategy in organizations. The practice of existential strategy can make us more authentically human. Once existential philosophy has been demystified by its translation into the pragmatic world of corporate strategy, its validity gains added power in enabling each of us, as individuals, to live lives of deeper authenticity and freedom.![]()

|

How Scenario Planning Explains Uncertainty |

|

Scenario planning is not the only tool of the existential strategist, but it is the preeminently appropriate tool for dealing with existential freedom. Scenario planning first flourished in the context of large corporations such as Royal Dutch/Shell Group of Companies, businesses whose planning horizon was so long that predictions based on extrapolations from the past would almost certainly be outrun by a fast-changing reality. Royal Dutch/Shell did well with scenario planning in the 1980s. When other oil companies were planning to increase prices for oil, on the basis of extrapolations from the price increases in 1973 and 1979, the planners at Shell developed a range of scenarios, narrative extrapolations from knowable potentialities, that included both price increases and scenarios for falling prices — a thought that was unthinkable to planners at the other oil majors. When oil prices crashed in 1986, Shell was the best prepared of the global oil companies, and its fortunes rose accordingly. Since the 1980s, scenario planning has been embraced by many other companies, so many that, by the turn of the millennium, scenario planning ranked as the No. 1 planning tool among corporations polled by the Corporate Strategy Board. Of course, this is good news for scenario planners. But it is also good news for everyone else. Scenario planning opens up a range of possibilities, for good and ill, much broader and wider than traditional tools that strive for a single right answer. Scenario planning helps us to entertain worst-case scenarios, as responsible managers must. Just as Heidegger argued that a sense of our own mortality can sharpen our sense of the fragility of our assumptions, so the development of best- and worst-case scenarios can awaken us to a sense of the preciousness of life. By encouraging thinking about a divergent range of possibilities rather than a consensus forecast, scenario planning can draw on both the motivation that comes from a fear of vividly depicted failure and the inspiration that comes from a skillfully drawn success. Upside scenarios can raise the sights of an organization mired in stagnation. Where essentialism condemns us to more of the same old thing, upside scenarios instill a sense of existential urgency about higher possibilities. Upside scenarios can function like the “inner game of golf” or “inner skiing.” Once you have mentally rehearsed the right swing or the perfect turn, you are more likely to be able to hit that drive or manage that mogul. There’s a lot to be said for the idea of mind over matter. But before the mind can steer matter in the right direction, the appropriate image needs to be framed as vividly as possible, whether it’s a golf swing, a ski turn, or a new success strategy. Upside scenarios can do for companies what a Tiger Woods tape can do for golfers. — J.O. |

Reprint No. 03405

James Ogilvy (jay_ogilvy@GBN.com) cofounded Global Business Network (GBN) in 1988. He is the author of Many Dimensional Man: Decentralizing Self, Society, and the Sacred (Oxford, 1975), Creating Better Futures: Scenario Planning as a Tool for a Better Tomorrow (Oxford, 2002), and, with Peter Schwartz, China’s Futures: Scenarios for the Fastest Growing Economy, Ecology, and Society (Jossey-Bass, 2000).