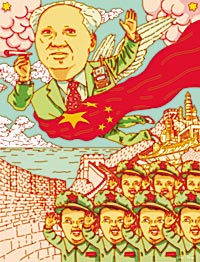

Profits and Perils in China, Inc.

The world’s most populous nation has become a capitalist’s paradise, supplanting Asia’s “tiger economies” — and soon, perhaps, the West.

(originally published by Booz & Company)During the next two decades, China will become a thoroughly new type of political and economic entity. It will be brutally competitive in both the political sphere and the marketplace, innovative and resilient in the face of turbulence, and more dominant as an international political and economic power than any nation except the United States.

This is the sort of change that takes place about once every century — comparable to the emergence of the United States as a world power at the beginning of the 20th century, or even to the rise of the Mongol, Incan, Alexandrian, and Ottoman empires. The magnitude of change in China is happening now, in part, because of a radical and rapid shift in its governance structure that has come to a head during the past few years. Because it has happened so suddenly, the temptation is strong to write this shift off as a fluke, or as just another temporary realignment of China’s business environment. But it is not. China’s restructuring is permanent and will affect every aspect of the country, from its microeconomics to its global identity.

In name and in many of its policies, China is still a Communist country. But the famous phrase “one country, two systems” (coined by China’s post-Mao premier Deng Xiaoping in 1992 to describe how Taiwan and Hong Kong could be assimilated into the People’s Republic but keep their economic systems intact) is more applicable than ever before. The People’s Republic now embodies two systems: the centralized autocratic Communist administration, dominated by outdated ideology and military interests, and the decentralized free-market economic regime.

Whether deliberately or not, China is reorganizing itself to balance central control and common purpose with decentralized freedom, in the same way that nimble corporations balance central and divisional control. The result is an entirely new geopolitical model — the country as corporation.

Chung-hua Inc.

One could call the new China Chung-hua Inc. (Chung-hua, or Zhong Hua, as it is spelled in Beijing, translates into English as “China,” and actually means “the prosperous center of the universe.”) One could also call it the United States of Chung-hua. For like many corporations, China is moving most of its decision making to the “business unit” level — only Chung-hua Inc.’s business units are semiautonomous region-states. Encouraged by the free-market system, smaller government bodies associated with China’s cities, regions, and “mega-regions” have become China’s new state equivalents. In a transformation largely unnoticed outside its borders, China is becoming an assemblage of economically autonomous regions, which compete fiercely against each other for capital, technology, and human resources (just as the states of the U.S. do).

To be sure, this new decentralized free-market regime has far to go before it encompasses all of China’s vast territory (and many Chinese officials still refuse to acknowledge its existence). But it is already dramatically changing the economic balance throughout Asia. It will do the same, eventually, in the rest of the world.

In the meantime, China’s renaissance is calling into question some of our prevailing assumptions about the most effective way to run a business, a consumer market, and a national economy.

I caught my first glimpse of this new China in the summer of 2000, on a visit to a three-year-old electronics components manufacturing plant in the city of Shenzhen in the Pearl River (Zhu Jiang) Delta. Located on the southern coastline near Hong Kong, the delta is one of the fastest-growing regions in China. This plant had 10,000 workers, earning about $80 per month each. They were all young women, and none of them wore eyeglasses. “Don’t you have any employees with bad eyesight?” I asked the manager. He replied, “We fire them when their eyes go bad. They can find another job — that’s not my problem. There are plenty of people who want to work for us.”

Such brutally cruel attitudes and practices do not exist in other nations of China’s stature because labor laws prevent them. But in Shenzhen, Shanghai, Suzhou, Dalian, and many more Chinese cities, where hundreds of millions of people eagerly flock to urban jobs from the hinterlands, such practices are taken for granted. One advertisement for a factory job in Dalian, offering the equivalent of $90 per month, drew 2,000 girls from nearby farmlands; they literally surrounded the plant seeking interviews. Those who are hired work around the clock and live in company dormitories. They often study electronic circuitry or other high-tech subjects on their lunch hours. Those laid off (for nearsightedness or other reasons) generally don’t return to the peasant life; they become urban entrepreneurs in the burgeoning freelance and service businesses of China’s new cities.

To find a precedent for a society comparable to China in 2002, you would have to go back 40 years, to the Japan of the 1960s, which was diligently preparing itself to become a global competitor. There are also echoes of Dickensian England — the dawn of the Industrial Revolution — and America’s “robber baron” era of the late 1800s, when the U.S. first showed signs of becoming a global economic power. But there are no such precedents in Communist nations, or in any country with such an inexhaustible population as China’s.

The Sleeping Giant

For decades, politicians, economists, and investors have speculated that China would soon wake up as a global economic powerhouse (although often quietly hoping that she was permanently content to sleep). Every five or 10 years, there was a burst of “China business fever.” Manufacturers outside the country thought, “If every Chinese person bought one of our shirts or televisions, we would have it made.” Then they began marketing in Beijing or Shanghai and came face-to-face with the difficulties of operating in China — the cavalier attitudes of the Communist government toward outside investment, the poverty, the fungible laws, and the corruption of officials — and soon their enthusiasm waned.

One can hardly blame observers for being skeptical about the prognostications of China’s dramatic change. Many people, including me, concluded that China’s potential for explosive growth was, if not illusory, at least unlikely. In The Invisible Continent: Four Strategic Imperatives of the New Economy, I wrote that becoming a prosperous nation was “simply not possible for China as a whole.”

But I did not know then how vibrant China’s regions were becoming. Nor was I fully aware of the other factors compelling China to wake up. The most significant was probably the 1998 appointment of Zhu Rongji (pronounced “Joo Rong-jee”) as premier of the State Council of China, the position once held by Deng Xiaoping. Even before he became premier, as a central banker, Mr. Zhu was known as the architect of China’s 8 percent annual economic growth and its dramatic reduction of inflation. He is China’s Jack Welch — known for his candor, his global sophistication, and his insistence on performance. And he is punishing to those who fall short of his expectations; as mayor of Shanghai, he once disciplined his tourist bureau officials by making them scrub out the city’s public toilets themselves.

A few months after his appointment as premier, Mr. Zhu delivered his “three promises” speech, in which he pledged to make three bold moves on behalf of a more vibrant, self-sustaining economy. First, he would overhaul the 300,000 state-run national corporations that still conducted an overwhelming amount of business in China. More than 70 percent of these companies were unprofitable and propped up by government subsidy. Just as Mr. Welch had promised to “fix, close, or sell” nonperforming divisions of General Electric Company 15 years before, Mr. Zhu threatened to fire chief executives of companies that lost money for more than two consecutive years, and then to either shut down or sell those companies. This forced national corporations to either be privatized and go public or be overseen by provincial governments, a change that has been a major impetus for the sudden decentralization of the Chinese governance structure.

Second, Mr. Zhu said he would wipe out the many bad debts of China’s banks and “international trust companies.” Many of them had contributed to China’s declining economy by routinely lending money to nonperforming parastatal corporations. At the time, there were 245 such trust companies, which had such a poor record of repayment that overseas investors were beginning to shun China entirely. Reforming them would take 10 years, he said.

Third, Mr. Zhu said he would streamline the central government and take on one of China’s most pernicious problems: high-level corruption in government agencies. This would mean, for example, cutting links between government and organized crime, and making it more difficult for bureaucrats to accept bribes.

Politicians sometimes make such promises — they have regularly made them in Japan during the past decade — but they rarely keep them. On July 1, 2001, at the celebration of the 80th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, Mr. Zhu assessed his progress. He had already fulfilled the first promise, he said: China’s public corporations had become profitable private entities or had been shut down. Those that were still operating were given stringent profitability targets, were allowed to choose the people they hired, and were encouraged to raise money on private stock exchanges, which effectively propelled them into the private sector as “red chip” corporations. As for the second promise, more than 50 heads of financial institutions had been fired, and reforms had changed the investment climate. Capital, instead of leaving the country, was flowing in more rapidly than ever before.

With regard to his third promise, the size of the central government’s State Council had been halved from 34,000 to 17,000 employees. Corruption was the only problem still festering, in part because of opposition to reform from vested interests throughout the government, at the highest levels. Nonetheless, his reforms have created the kind of level playing field and rule of law in China on which a vibrant capitalist system depends.

The Region-States

Mr. Zhu’s reforms are reinforced by the rapidly evolving Chinese government structure. Only seven years ago, the word federation was banned from the Chinese language; companies like Federal Transport or Federation Merchants were required to change their names. Today, China has the most federal governance structure of any large nation except the United States; it is well on its way to becoming a commonwealth of semi-autonomous, self-governing economic region-states.

There are actually two broad categories of region-states. The first are relatively small, composed of cities and their surrounding areas, generally with a population of 5 to 7 million people. Some of these smaller region-states, such as Shenzhen, Shanghai, Dalian, Tianjin, Shenyang, Xiamen, Qingdao, and Suzhou, are now growing at 15 to 20 percent per year — far faster than such Asian “tigers” as Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, and Korea. These smaller region-states, in turn, are part of (and propelling the growth of) larger mega-regions, with populations approaching 100 million each.

The larger mega-regions, which tend to share common dialects, ethnic identities, and histories, are becoming economic powerhouses in their own right. If they were separate nations, five of them — the Yangtze Delta, the Northeastern Tristates area (formerly known as Manchuria), the Pearl River Delta, the Beijing-Tianjin corridor, and Shandong — would have Gross Domestic Products ranking among the Asian top 10. As shown in Exhibit 1, they would outrank Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines. (Two others in the top 10, Taiwan and Hong Kong, are largely populated with ethnic-Chinese people, as is 11th-ranked Singapore.)

Although China is officially Communist, businesses in its region-states have far fewer regulations to deal with than their counterparts in Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Germany, France, and Sweden. Even by comparison to the U.S., China is a capitalist’s paradise, so long as you remain within these regions and do not deal with the central government in Beijing. For example, tariffs (which are set by the central government, but administered locally) are low or nonexistent for the many companies that take advantage of China’s regional systems of tax-free zones and tax benefits. In most of the mega-regions, protection of domestic industry is not a political priority. Instead, officials seem to subscribe to the notion that by welcoming foreign businesses in, and allowing unfettered competition, they can make their own industries stronger. So far, they have been proved correct; I have Japanese and American friends who opened subsidiaries in China around 1998 or 1999, and made a great deal of money during their first two years. But now they are competing with fast-growing, fast-learning ventures led by shrewd Chinese entrepreneurs; once again it is difficult for outsiders to make a profit.

Regional Chinese governments have also been toughened up by the Chung-hua Inc. ethic. Most officials in China are appointed, not elected, but their posts are not sinecures. Not only are officials held to targets of 7 percent economic growth per annum or better (like many corporate executives), they must also continually improve environmental quality, build better infrastructure (transportation, port facilities, communications, energy, and sewage), and lower local crime levels. In October of 2001, a half-dozen bureaucrats were expelled from one of China’s major cities for not meeting their economic growth and security targets.

To the people living in these regions, local government officials, far from being seen as oppressive, are often considered heroes. In January 2001, Bo Xhi Lai, then the mayor of Dalian, was promoted to governor of the Liaoning province. Thousands of women spontaneously came to the park to say goodbye to him; many were in tears.

Mr. Bo, who is six feet two inches tall, is also strikingly handsome and charismatic. But the real reason these women turned out, I suspect, had more to do with Dalian’s evolution under his tenure of nine years from a ramshackle port town to one of the most prosperous and environmentally clean cities in Asia. Dalian has a more vibrant street life than Singapore, a layout reminiscent of Paris before the automobile, and a reputation among Japanese tourists for high-quality hotels, transportation, and restaurants.

Dalian is also home to a number of high-tech industrial parks and dozens of universities and research institutes. Twelve thousand foreign companies are located there, of which 4,000 are from Japan. Within an hour’s drive from the city limits, there are hundreds of thousands of peasant farmers, with an annual income of $300 per capita, but they now have daughters and granddaughters who are white-collar employees in the city, all learning to live with affluence. Everyone, including the farmers, seems to be happy with this progress.

Economic Milestones

China has benefited from a series of well-timed — or shrewd — economic and political strategies. One was the 15-year-long process of gaining admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO). China has been gradually liberalizing most of its trade policies for some time. So, its admission to the WTO is largely symbolic. More pertinently, WTO membership represents China’s commitment to establish clear, enforceable rules regarding intellectual property and copyright protection.

Less noticed, but equally meaningful, has been the move to stabilize Chinese currency. In 1997, when Hong Kong was returned to China, the United Kingdom agreed to leave about $38 billion of reserve capital in the territory — but only if the Chinese promised to keep the currency intact for 50 years. It was stipulated that for every new Hong Kong dollar (HKD) minted by its three central banks, the equivalent of U.S. 13 cents would be held in reserve. The Chinese not only accepted this, but pegged their mainland currency, the renminbi (RMB), against the Hong Kong dollar. They also prohibited exchange of RMB outside China, limiting speculators to the HKD. In effect, by embracing a restriction against minting money to relieve economic pain, China made itself immune from the currency fluctuations that have bedeviled such developing nations as Mexico, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, and Argentina.

Apparently because of pressure from other Asian countries, China’s leaders recently announced that they are considering decoupling the RMB from the HKD, which would presumably make the RMB more expensive and reduce China’s export competitiveness. But in the meantime, with its de facto dollar-based economy, China enjoys the same protection against inflation that the United States does. As its economy has improved, investment capital has flowed steadily to China. Before 1992, investors had shunned China because of its economic unreliability. Starting with the proclamation of “one country, two systems” that year, money began flowing into the stock markets in Shenzhen and Shanghai, as did direct investments to build plants and offices in tax-free zones.

Within China, it is practically a national sport to invest in stocks. The enormous worldwide population of expatriate Chinese people — 60 million to be exact — also is prone to investment, and they have eagerly taken advantage of their linguistic, ethnic, and family ties to put their money back into mainland China during recent years. Some are also returning to China as entrepreneurs. Nearly $45 billion entered China as foreign direct investment in 2000, according to Economist Intelligence Unit estimates, compared with about $10 billion entering Japan, and even less for the Asian tigers. (See Exhibit 2.)

Much of the money has gone directly into improving industrial productivity. A typical Chinese factory used to consist of rows of workbenches with women sitting at them. Today, Chinese factories are as modern as their Japanese counterparts, with sophisticated machine tools, surface-mounting technologies for circuit boards, robots, and other automated equipment. China has also made a serious commitment to building roads, telecommunications lines, Web switches, sewage systems, electric power supplies, modern port facilities, and other infrastructure. China now has 130 million cellphones, more than the United States or Japan.

The Chinese have also leapt wholeheartedly into the challenges of global competitiveness. Once, most Chinese business managers were Communist Party ideologues, uninterested in either developing their people or improving quality. Today, Chinese managers are fired if they don’t perform, and they are learning management skills faster than the industrialists of any other nation I have studied, including Japan. It’s not unusual to meet a manager who attended one of China’s elite foreign-language schools (which were oriented toward spy training during the Cold War era), who opted for a career in business instead of espionage, and who then went to the United States for an MBA. China’s managers practice just-in-time manufacturing, 360-degree performance evaluations (including bosses reviewed by subordinates), Six Sigma process improvement, and reengineering — all with a resourcefulness and purposefulness unmatched elsewhere. Jack Welch’s face on the cover of his new book is in the windows of bookstores across China. It may well be the most popular book there — even though Mr. Welch may not get royalties because it’s probably a pirated edition. (China’s entry into the WTO will be stimulus for better copyright protections, but the Chinese clearly have a way to go.)

During the 1970s and 1980s, I was a close adviser to several Japanese companies that cracked the U.S. market. I vividly remember the resourcefulness and aplomb of their executives, who confronted each new challenge by asking, “How can we do this?” Today’s Japanese corporate leaders tend to blame the economy and government when a problem arises: “We can’t do anything,” they say. But Chinese companies have picked up where the Japanese left off; they are developing innovative, low-cost export businesses in apparel, footwear, vitamins, foods (including exotic mushrooms popular in Japan), watches, consumer electronics, appliances, and precision electronic and mechanical components.

China’s Corporate Powerhouses

As a nation, China has had a reputation for some time for being a lackluster source of innovation. Suddenly, however, that estimation is changing. Consider the story of Neusoft Group, a Shenyang-based software company named after the city’s NorthEastern University, where many company managers are professors. According to Asiaweek.com, Neusoft is China’s largest publicly listed software company, with sales of $134 million last year; among its accomplishments is the Neu-Alpine Software Company, a joint venture with the Japanese firm Alpine Electronics Inc. and the first major Chinese software producer to be listed in the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

Neusoft began as a lower-cost competitor to the Oracle Corporation, and has now moved on to produce car audio equipment and medical imaging devices. CEO Liu Jiren, hearing complaints from local hospitals about the high cost of specialized analog X-ray, MRI, ultrasound, and CT-scanning machines (such as those made by GE, Philips, Siemens, and Toshiba), realized that his company could link standard Intel chips and its own imaging software to a range of digital sensors. Neusoft’s scanners don’t look like conventional medical equipment; they look like little personal computers with sensors attached. But they are inexpensive and adaptable enough that every hospital room can now have its own multipurpose scanner. Such a startup in the U.S. or Japan, facing entrenched industry opposition, might never have gotten off the ground; by selling to Chinese hospitals first, however, Neusoft has built up a customer base that will allow it to challenge the existing medical electronics industry worldwide, just as Honda Motor Company and the Toyota Motor Corporation challenged the worldwide auto industry in the 1970s.

Neusoft is just one of many inventive companies that I have visited in China. Little Swan sells washing machines in 40 countries. Legend Group is currently the world’s largest manufacturer of personal computers (they are sold mostly under other brand names). Hua Wei, headquartered in Shenzhen, makes routers and telecommunications switches at half the price that most global companies charge. It has 14,000 employees (70 percent of whom are engineers) and a plant as modern, pristine, and collegial as those run by Nike Inc. and the Microsoft Corporation in the United States. Many top-tier American and European telephone equipment manufacturers fear Hua Wei more than they fear Fujitsu Ltd. or the NEC Corporation. Japan’s Fast Retailing Company Ltd. manufactures high-quality clothing in China, reducing distribution costs by making only one design per plant and retailing the garments in its own Japanese outlets under the Uniqlo brand. Fast Retailing charges one-third the price that competitors charge and earns nearly five times the margin. (See Exhibit 3.) The company has made such an impact on Japan that the verb “to uniqlo-ize” (to dramatically cut costs through Chinese production and eliminating intermediaries) has entered the Japanese business vernacular, as in: “Can we uniqlo-ize the housing industry?”

Precisely because the domestic market in China is so large, many Chinese companies will turn their attention overseas only when the domestic market is satisfied. This was not the case in 1970s-era Japan, where the internal market was already dominated by kieretsu. Other Japanese companies, like Sony and Honda, had to concentrate on exports from day one. Because China is still a developing nation, its companies are not ready to build global brands. But they are poised to become the most capable and competitive original equipment manufacturers — producers of goods sold under other brand names — that the world has ever seen.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the hidden key to Japanese success was the existence of two regions — Otaku in Tokyo, and Higashi Osaka in Osaka Prefecture — where thousands of manufacturers of high-quality precision mechanical and electronic components (lenses, molds, capacitors, semiconductors, and so on) were clustered together. Visible and branded companies like Toshiba and Sony depended on them for their success. Today, Otaku and Higashi Osaka operate at half their former capacity; they are being underpriced out of business by the Chinese. More than 100,000 component manufacturers, most of them from Japan or Taiwan, have relocated to the Pearl River and Yangtze River Delta regions. These regions always had cheap labor, but in the past it took nine days to receive deliveries from suppliers in Japan. Now, with modern highways, port facilities, and communications links available, a cell-phone manufacturer in Shenzhen might receive just-in-time deliveries of components several times a day from hosts of high-quality suppliers that are only hours away.

Dalian is becoming a center for software development and Japanese-language “back office” work, such as insurance processing, software development, and call centers. Qingdao, on the Shandong Peninsula, is home to companies that produce high-quality processed food; 80 percent of Japan’s food imports from China come from here. If you are a company like Nike looking for skilled textile production, you go to Fuchien; if you want aerospace and heavy machinery, you go to Shenyang. If you want high-level research, you might go to Zhongguancun, a zone in Beijing the Communists established for military research during the Cold War; it is now home to 68 universities and more than 200 research institutions, many making the transition to commercially sponsored research. Half a million scientists and engineers work there, in such fields as electronics, optics, bioengineering, medicine, materials science, and energy efficiency.

Each of these region-states has its own clusters of component suppliers and professional service providers, with an infrastructure of transportation lines, communications networks, and research laboratories to support them. Region-states have learned to specialize by competing fiercely against each other for business with foreign investors. Both region-states and mega-regions are developing their own links to the outside world — through air, sea, and telecommunications — independent of the central Chinese government. There are 4,000 Taiwanese manufacturers in the southern cities of Xiamen and Dongguan; Japanese companies prefer Dalian, Qingdao, and Tenjin; Europeans favor Shanghai; and American high-tech companies settle in Beijing.

Quiet Capitalism

China sends tens of thousands of students to universities in Japan, the U.S., and Europe. Many of them stay overseas, but now the Chinese region-states are actively (and successfully) recruiting them to come back. The Dalian local government has constructed an elaborate software development park to establish a Silicon Valley–like atmosphere; it includes an enormous incubator building where students returning to China from abroad can rent low-cost office space for startups and benefit from broadband network environments, introductions to investors and financial angels, and — not least of the attractions — exposure to each other. Like rival businesses in a single large corporation, other cities, including Beijing and Shenzhen, are creating their own incubators and talent attractions as well.

Of course, all of this is taking place within the confines of a nation that still has a strong Communist ideology, that in many respects is still a military dictatorship, that occasionally talks about conquering Taiwan by force, that has armed many belligerent nations, and that ruthlessly uses North Korea, Pakistan, and Libya (for example) as its stalking horses for war or for missile development. Thus, much of China’s new commercial renaissance occurs quietly, without the official or explicit blessing of the central government. The introduction of foreign companies, technologies, and capital, and the unfettered migration of corporations and people across boundaries, would all be seen as threatening to the Communist system — if it were publicly acknowledged. The whole delicate balance depends on nobody admitting that China is becoming as much a de facto federation as a centrally controlled system.

In her book Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics, social critic Jane Jacobs proposes that there are two separate and contradictory sets of ethical values in human civilization — one for military and government “guardians” charged with protecting society, and another for commercial traders and merchants who prosper through exchange. In China, the central “guardian” officials, steeped in Communist doctrine, still insist that they run the most centrally controlled government in the world, with full authority to appoint or dismiss mayors, governments, and bureaucrats. Strictly speaking, the central officials are correct; they have the power. But if they value their country’s prosperity, they dare not overrun the commercial ethic of China’s region-states.

The tasks of peace are thus left increasingly to the region-states, cities, and corporations; only the tasks of war remain for the dictatorship. (The U.S., although very different, embodies the same tension; in peacetime, it is an open commercial nation, but when attacked, as it was on September 11, its military guardians take center stage and CNN’s airtime.)

Some fear that when Zhu Rongji retires (he says he wants to do so in July 2002), China might revert to central control. But that would mean undoing the investment and development that has already taken place and reversing the new quality of life that Chinese people celebrate. It’s unlikely, but it could happen.

Another potential threat to the new balance, some believe, is the disparity between the rich coastal regions and the impoverished inland areas. However, quality of life has risen inland as well, and China’s industrial renaissance will likely continue migrating west, where labor is less expensive, bringing infrastructure and higher standards of living along with it. For signs of discontent, we need to look outside China’s borders.

Asia’s Crisis and Its Tiger

It took the Asian tigers — Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Korea — more than 15 years to build their economies into symbols of new development. It is taking China only a few years to supplant them. Thus far, whenever China has competed directly with another nation’s industries, China has won. Malaysia and Thailand spent 10 years building the expertise, production base, and infrastructure for a precision metalworks that could sell components to Swiss watch manufacturers. The Chinese took over that business in only a year. The same is happening with electronics and machinery. Since 2000, the currencies of Taiwan, Singapore, Korea, Japan, Thailand, and Indonesia have declined precipitously, according to currency trend analysis from Oanda.com. Stock prices of major Asian countries have also been devastated, particularly when compared to China’s.

Some countries, like Japan, Singapore, and Taiwan, suffer more from Chinese competition today than they suffered from the 1997 Asian economic crisis. That currency crisis, triggered by such noted speculators as Julian Robertson, the former head of the now-defunct Tiger Management Group, and George Soros, a founder of the Quantum Fund, was simple and short-lived. The second Asian economic crisis, just beginning in 2001, will not go away so easily.

China is doing to the rest of the Asian economy what Japan did to the West 20 years ago. Each of the Asian tigers has its own tale of woe. Singapore and Taiwan, for example, came through the 1997 turmoil relatively unscathed, but now their manufacturers simply cannot compete with China’s. Singapore is thus becoming a kind of Asian Switzerland, betting its prosperity on investments in China’s growth. Significantly, Singapore’s former prime minister Lee Kwan Yew has become the chairman of the government pension fund, a major investor in China. His is now the most powerful position in the country.

Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand have been equally hard-hit, but they lack Singapore’s resources and imaginative strategy. They are likely to suffer deprivation, fragmentation, and unrest, with perhaps some resentment brewing toward the people of Chinese descent within their borders. Vietnam would seem able to compete — its labor costs are even lower than China’s — but the government is so corrupt, the business regulations so onerous, and the infrastructure so poor that it is rapidly being deserted by foreign investors. Malaysia is keeping its well-established electronics industry but losing its newer businesses in electronics and machinery. India will lose some of its software business to Chinese companies (whose employees also speak English, the language of software development). However, it will retain its lead in highly complex architecture and applications programming. Other Asian countries that might have become tigers — such as Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar — will no longer have the chance.

And then there is Taiwan, formerly one of the most prosperous countries in Asia. Despite restrictions on direct contact with China, many Taiwanese businesses are quietly relocating their factories and wealth there. Sooner or later, Taiwan may find itself forced to reconcile with China — not for military reasons, but because Taiwan will want to participate in the many opportunities on the mainland. Today, Taiwanese businesspeople cannot fly, telephone, or ship product directly between their sites in, for example, Taipei and Xiamen without passing through Hong Kong or Jinmen Island. If that continues, Taiwan will hollow out as its entire business system migrates across the Taiwan Strait.

The Threatening Opportunity

What, then, does the new Chinese juggernaut mean for Japan, Europe, the United States, and other wealthy regions? For consumers, it is an unalloyed boon. Chinese industries will cut costs, raise quality, and propel innovation for most consumer and industrial products — not just because of their own efforts, but because global companies vying for position in China are putting their own best practices to use there.

Japan is already discovering the bitter truth: It is suddenly extremely difficult for a non-Chinese company to compete in any worldwide market with a strategy of low-cost, low-price commodities, even if those commodities are precision electronics components. Very few commodities are out of reach for Chinese industry, which (unlike that of any other nation) can marshall low-cost labor and high-tech automation at the same time.

Successful businesses henceforth will be those that establish and maintain highly reputable brand names. Japan will orient itself toward research and development, software, design, and its unique high-precision robotics and machinery. The Japanese “look and feel” will undoubtedly sell well to the vast new Chinese middle class, which will view Japan as Americans view France, Italy, and Germany — as sources of high-quality and luxury goods that confer status upon their owners. Honda is already discovering the Accord sells at a premium in China.

Because the Chinese are neither skilled nor experienced at marketing, it will take at least five or 10 years for them to develop global brands for their best goods — specifically, appliances, electronics, processed food, possibly automobiles, and perhaps new technological innovations in energy or materials. In the meantime, the Chinese will take over many commodity, industrial supply, and nonconsumer-brand industries. Like the U.S. in the early 20th century and Japan in the 1980s, China will overcome protectionist efforts against its companies. People around the world will demand the goods China can provide at a lower cost and higher quality than any other nation can.

This will lead to a frenetic new wave of competition, but not between China, the U.S., and Japan as monolithic entities. In each industry and region, there will be a race to see which companies can most effectively internalize China’s new methods and approaches to beat its local and immediate competitors — just as U.S. management methods have been internalized by companies around the world, including some in China.

The U.S. confronted something similar: the Japanese challenge of the late 1980s. Many businesses adapted and came out stronger as a result. America, which is very good at internalizing foreign competitors like Bayer, Nestlé, Sony, Toyota, and DaimlerChrysler (in effect, making them into American companies with American investors, industries, loyalties, and even corporate cultures) will undoubtedly succeed in the long run at internalizing Chinese companies and galvanizing its own to higher levels of innovation.

That doesn’t mean that China should get the free-market system’s blanket approval. Quite the contrary; the country has never been so dangerous. It still maintains a highly centralized military, many of its leaders still profess Communist ideologies, and it still does not tolerate dissent. At the same time, I do not believe China should be forced to hold democratic elections, even if that were possible. Its population would vote for leaders who distribute wealth to the poor. But there are still 900 million farmers in China with an average annual income of $500; distribution of wealth would simply be a synonym, as it is in India, for the distribution of poverty.

The Western debate over China’s political acceptability should not be cast as a simple matter of right or wrong, but of when and how. Politically, China is comparable to the United States of 1800: an emerging nation with high ideals but widespread poverty and a great many practices that other regions find intolerable. People tend to forget that the U.S. did not establish civil rights legislation until the 1960s. A decade or two of economic growth, under the shrewd and highly motivated leaders of Chung-hua Inc., will provide China’s people with the necessary education in the ways of capitalism, just as working for a large corporation does the same for young managers. It will also give the Chinese people an appetite for self-determination and participation because they will see what their efforts can achieve. That, in turn, may lead to a country whose openness and capability for democracy ultimately surprise the rest of us. Already, some village leaders are elected; this may slowly spread to regional officials, and then upward to the central government.

In the meantime, China’s growth will put politicians of other nations into an unprecedented situation — greater than the challenge posed by Islamic extremists. China will continue to threaten the political status quo of the rest of the world, both diplomatically and economically.

But remarkable changes in China over the last 18 months suggest that the outcome may be the opposite of what many people fear. Recently, China’s head of state, Jiang Zemin, said that the Communist Party “represents” every good aspect of China, including wealthy capitalists. This directly contradicts the long-held position of the Communist Party, which claims to represent only the poor, the exploited, and the proletariat. I will not be surprised if soon — perhaps at the Communist Party’s 2002 General Assembly — Mr. Jiang and Mr. Zhu formally announce the end of Communist ideology as their guiding principle and call for a gradual shift to a new doctrine. In that case, Chung-hua Inc. will become a reality.

Whether that takes place or not, China will present the world with unprecedented challenges, and we will see a great deal of resentment expressed by both politicians and businesspeople. But as consumers, we will have never had it so good, and we will soon come to depend on the quality and lower-cost goods that China can provide better than any other nation. When we finally do meet the enemy, over in Beijing, we will discover that they are us. ![]()

Reprint No. 02107

| Authors Kenichi Ohmae, kohmae@work.ohmae.co.jp Kenichi Ohmae is managing director of Tokyo-based Ohmae & Associates. Mr. Ohmae, a corporate strategist and advisor to governments around the world, is a former director of McKinsey & Co. and chairman of its Asia-Pacific operations. He is the author of dozens of books and writes frequently for major business publications worldwide. |