A time-tested strategy for leaders facing a “perfect storm”

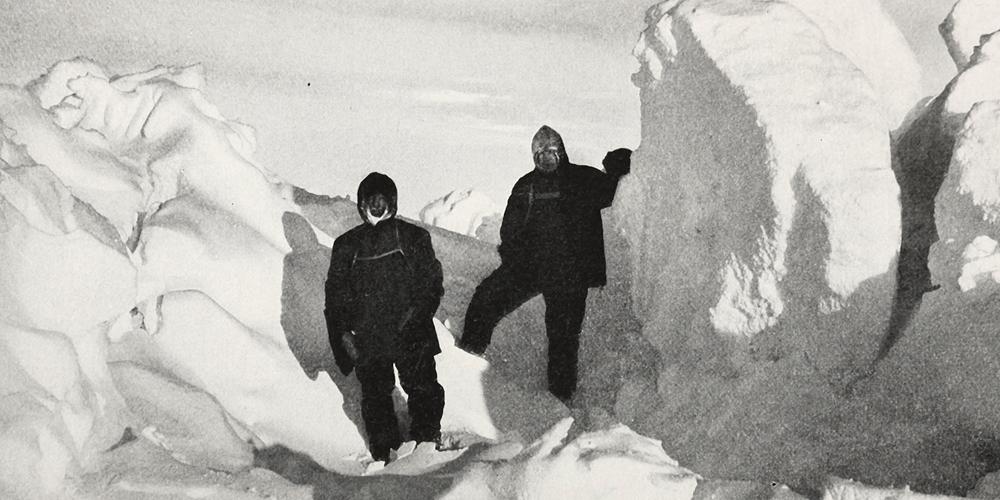

The great polar explorers all had seconds-in-command to help manage their teams. The role is still needed in organizations today.

A perfect storm is the term for treacherous, simultaneous weather and oceanic conditions—such as strong waves, powerful winds, and torrential rain—that conspire to create dangerous seas. In business, leaders are facing a perfect storm of a different sort. Talent wars, actual war, the pandemic’s disruption to business, and inflation are just some of the issues troubling businesses today.

So who can help executives navigate these difficult waters? For the past decade, I have researched some of the most dangerous and difficult polar expeditions to see how their leaders managed the many perfect storms they faced. I’ve come to the conclusion that having a second-in-command on a team, no matter the team’s size, was a defining feature of a mission’s success.

In my book When Your Life Depends on It: Extreme Decision Making Lessons from the Antarctic (coauthored with David Hirzel), I described the early Antarctic expeditions that led to the conquest of the South Pole in the early 1900s, as well as a greater scientific understanding of the continent. My goal was both to understand the life-and-death decisions made by the explorers and to explain why six specific expeditions stood out as the most significant—and most unified and successful—among all the Arctic or Antarctic expeditions at that time.

Antarctic expeditions in the early 1900s were exceedingly dangerous, and they faced a perfect storm of terrible conditions: blizzards, scurvy, starvation, hypothermia, frostbite, snow blindness, and falling into a crevasse, among other constant perils. What fascinated me was the potential these conditions created for people to resort to murder and mayhem. Yet for these six expeditions—two led by Robert Scott, two by Ernest Shackleton, one by Roald Amundsen, and one by Douglas Mawson—none of the negative human risk factors occurred, even though these were multiyear endeavors in the most challenging of circumstances.

So why did the expeditions and their leaders perform so well? My conclusion was that everything they did was done in teams. Goals were clearly defined and understood by all involved. And most important, the team leaders had a second-in-command on all teams.

The names of those in the expeditions’ second-in-command posts might not be as famous as that of Ernest Shackleton, but in polar historian circles, these men are absolute legends. Edward Wilson was the second-in-command of English explorer Scott; he was the chief scientist and medical officer on both of Scott’s expeditions, and he served as the peacekeeper among the men. He was especially helpful to Scott after the famed Norwegian explorer Amundsen announced that he was challenging Scott to be the first to the South Pole.

Wilson wisely advised Scott to adhere to the original scientific goals of their first expedition, rather than change priorities and focus solely on attaining the Pole. Wilson was seen by the men as a calming influence on Scott; he also was able to keep the scientists and other men on the expedition focused on their data-collecting and analysis tasks instead of obsessing over who reached the Pole first. Thanks to Wilson, the scientific findings of Scott’s expeditions live on (despite the tragic ending of the team’s final expedition), and form the baseline for Antarctic climate change research today.

Frank Wild was Shackleton’s second-in-command, but at times the role was filled by Frank Worsley and Tom Crean. After Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, sank—a ship that recently was discovered at the bottom of the Weddell Sea—it was Wild who maintained the team’s morale; he and 21 other men were marooned on Elephant Island for four-and-a-half months while Shackleton and a small crew sailed a lifeboat across 800 miles of the roughest seas in the world to seek rescue. Remarkably, all the men on Elephant Island lived because Frank Wild bonded them as a team. He didn’t bond them because he was the expedition’s leader—that position was reserved for Shackleton, whom everyone referred to as the Boss—but because he clearly was the second-in-command, even when Shackleton was not on Elephant Island.

Modern equivalents

I recently raised the topic of having a second-in-command with Helen Dwight, a senior marketing leader who has worked on three continents for major tech companies. She believes firmly in having one or more potential second-in-command employees, depending on team size, and has followed this practice throughout her career at companies including Oracle, Informatica, and now SAP. “Having a second-in-command, even on small teams, helps to ensure team cohesion,” she told me. “A second-in-command is well-placed to manage business challenges between team members. And team members are more willing to talk openly to someone who doesn’t have salary or performance review authority over them.”

Having a second-in-command, even on small teams, helps to ensure team cohesion. A second-in-command is well-placed to manage interpersonal conflicts among team members.”

Dwight also finds it to be a good way to assess candidates for promotion. Some people excel in the second-in-command role, while others find that they prefer their role as an individual contributor. It also enables people to experience some managerial work before seeking a full-time managerial role. And it helps with succession planning: having a proven and experienced second-in-command means that it’s easier for the leader to move higher in the organization, because there is someone to step into their former role who can ensure continuity and consistency.

My own experiences bear this out. When I worked as a manager in a tech company that had a second-in-command, I felt I could air my concerns without jeopardizing my position with my boss. We could brainstorm solutions to problematic assignments, tasks, projects, and customer situations, and work out viable action plans. The same was true for raising new ideas that might have seemed half-baked—I could first approach the second-in-command for feedback, refining the idea before taking it further up the chain of command. And being able to discuss personal situations and requests with the second-in-command—without bothering the boss—gave me an added sense of loyalty to my organization. In all these cases, the management structure reinforced my ability to execute and reduced the stress of making a mistake, becoming disgruntled, or bothering a more senior executive.

Recently, I was discussing the second-in-command concept with Barry Freedman, president of Kooltronic, a US-based manufacturer of medical and industrial air conditioner units. Freedman didn’t think he had second-in-command roles at his company, but as we got further into the conversation, he realized that one of the leads reporting to the assembly supervisor—a lead with years of experience and knowledge of function—serves as a de facto second-in-command in that key area of the business.

It's possible that people are fulfilling de facto second-in-command roles at your business, too. If you find one or more, it’s worth studying how they are performing, and the value they bring. It is also relatively easy to try assigning talented individuals to second-in-command positions on various teams within your business on a trial basis to assess how the role would perform. Finding the unsung heroes—the equivalents of Wilson, Wild, Worsley, and Crean—in your organization could give it a competitive edge.

Author profile:

- Brad Borkan is the coauthor of two books, When Your Life Depends on It: Extreme Decision Making Lessons from the Antarctic and Audacious Goals, Remarkable Results: How an Explorer, an Engineer, and a Statesman Shaped Our Modern World. A former senior director at leading high-tech companies, he is a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, Vice Chair of the Friends of the Scott Polar Research Institute, and a member of the Society of Authors.