Closing the Culture Gap

Linking rhetoric and reality in business transformation.

A version of this article appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of strategy+business.

Leaders today are well aware that their organization’s culture is an asset that must be managed with purpose and care. The trouble is, there isn’t a playbook that makes it obvious how to do this. Sometimes, even the most well-meaning CEOs don’t fully connect with the real issues that motivate people. This critical gap — between leaders’ perceptions of what people care about and the actual realities of the culture — can prevent a company from achieving its desired results.

Fortunately, it’s possible to close this gap. Armed with a deeper understanding of their company’s culture and the day-to-day behaviors that shape it, leaders can find new opportunities to achieve their business goals — and new allies to help drive the effort.

Consider this scenario: Monday’s all-hands meeting in the auditorium was not going according to plan. Andrew, the CEO of a hotel chain rocked by disruptive technology, had called the meeting to promote his new culture initiative. He’d planned this presentation to reenergize the enterprise. He was invigorated by a vision of the company as a place where ideas would flow freely and innovative solutions would burst forth from all players. The rest of the campaign to follow was carefully designed, with clever posters and weekly reminder emails. By year-end, Andrew was certain that he would see tangible improvements in the mood in the halls, in the conversations within both the cafeteria and the offices, and, ultimately, in business performance.

But the reception to his presentation fell far short of his expectations. The audience was quiet. From the podium, Andrew couldn’t help but notice employees scrolling through their phones. He could practically hear crickets chirping during the Q&A. A few members of his leadership team gave him a thumbs-up as he left the stage, but Andrew felt deflated and baffled. Where had this gone wrong?

Andrew would have been crushed if he’d overheard the postmortems in the break rooms. “What a waste of time,” one team leader said. “A lot of fine words and pretty pictures, but nothing about how things really work around here.”

A team member chimed in: “And did you hear that bit about celebrating experimentation and fast failure? Yeah, right. All you get when you fail in this company is a bad review and no bonus.”

“Oh, well,” the team leader replied. “At least we know it will all blow over as soon as management finds the next shiny new ‘culture initiative’ to focus on.”

Beyond Disappointment

As a leader, have you ever found yourself in Andrew’s shoes — eager to demonstrate your commitment to improvement, but unsure how and where to begin such an effort? Or maybe you’re like his leadership team members, or the line employees. You see leaders trumpeting “culture change,” and you want to be encouraging, but you have private doubts. You agree that the organizational culture needs work, but you suspect that the path being described won’t lead to anywhere other than where you are today.

What’s an organization to do? How can you connect the dots between having high aspirations for improving culture and making lasting changes that lead to real results? What’s the secret?

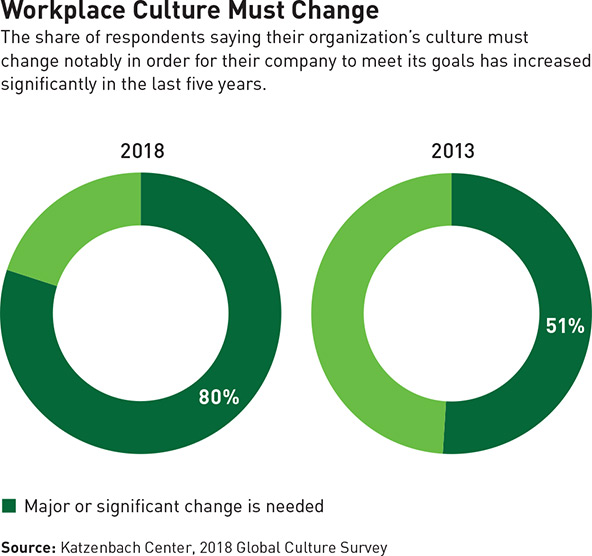

Through conversation after conversation with leaders at all levels, we and our colleagues at the Katzenbach Center at PwC’s Strategy& have come to recognize that stories like Andrew’s are common. Many leaders launch sweeping change initiatives with high aspirations, only to be disappointed by the results. Most leaders believe (accurately) that a purposeful shift in culture is necessary to transform their business, but few know how to make this leap. Google search data shows a massive increase since 2013 in queries on the term company culture. Scores of books, articles, and speeches on the topic compete for readers’ attention. Responses to the Katzenbach Center’s 2018 Global Culture Survey demonstrate this same curiosity and urgency with respect to the topic. More than 2,000 respondents representing a broad cross-section of organizations — in 50 countries, and almost as many industries — were asked whether they believed that their organization’s culture must change significantly in order for their company to meet its goals, and 80 percent agreed.

The strength of this response is remarkable, as is the shift it represents from previous years. Five years earlier, only 51 percent of respondents answered in the affirmative to a similar question (see “Workplace Culture Must Change”). Further, a hefty proportion of individual respondents have seen culture efforts fail. Respondents were asked whether their company had undergone an effort to evolve their culture; a majority agreed. Of those who agreed, a full quarter then reported that these efforts had not been rewarded with any discernible change in how people behaved.

How can this curiosity about culture, and determination to address it, translate into effective results? Through our work and research, we’ve come to believe that making a real, emotional connection with employees is the way to convert rhetoric about culture into sustainable behavior change. And understanding and working within your culture, we’ve concluded, is the secret to this kind of emotional engagement.

The Perception Gap

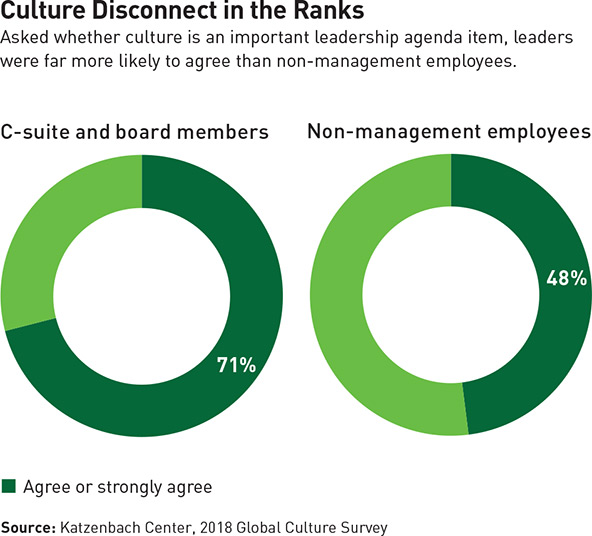

Every leadership team — whether its members are willing to admit it or not — is afflicted with some degree of cultural myopia. This is the tendency to see only the team’s own point of view, without fully acknowledging the perspective of others outside the team’s ranks. Again, our survey data backs this up. Survey respondents were asked whether they believed that culture was a priority on the leadership agenda of their organization: 71 percent of C-suite and board respondents answered in the affirmative, compared with only 48 percent of those in non-management roles (see “Culture Disconnect in the Ranks”). In other words, across industries and around the globe, C-suite executives’ opinion of their ability to manage their cultural situation is far higher than the opinions held by people further down the line. This demonstrates how prevalent the culture gap is, and why the need to close it is urgent and undeniable. Leaders can’t expect to see results from culture initiatives unless they connect with their organization on an emotional level. They also must work with, rather than against, the grain of how people already think, feel, behave, and work together.

Escaping Cultural Myopia

After the all-hands meeting, Andrew caught up with one of the executive team members, Sandra. Sandra was not among the leaders who had offered Andrew a bright smile and a thumbs-up when he left the stage; rather, she’d given him a look of empathy and signaled, “Call me.” And so he did. The two sat down over coffee the next day.

How can curiosity about culture, and determination to address it, translate into effective results?

Sandra was a new hire; she’d joined the leadership team just a few months earlier. At her previous company, Andrew learned, she’d been on a team that had led a culture initiative. She described what she’d seen: Even the most well-intended and well-funded culture pushes won’t work when there is a disconnect between what the C-suite is communicating to its people and what these leaders are doing every day. “Often,” Sandra said, “leaders have a much higher opinion of a culture initiative than the folks on the ground. We need to be aware of that. That’s the first step forward.” Together, Andrew and Sandra began to hammer out a plan, a new approach that relied less on posters and more on real, human interactions.

Go Broad, Then Deep: The “Critical Few”

In their forthcoming book, The Critical Few: Energize Your Company’s Culture by Choosing What Really Matters, our colleagues Jon Katzenbach, Gretchen Anderson, and James Thomas lay out a reliable method for fostering culture evolution. This process involves inclusion and selection: gathering input and broad perspectives; narrowing down to actionable, targeted steps and goals; and tying behaviors to strategic objectives in order to measure success.

First and foremost, you must identify your organization’s “critical few” traits: the core attributes that are unique and characteristic to it, that resonate with employees, and that can help spark their commitment. Next, you develop the critical fewbehaviors that, if executed repeatedly by more people more of the time, will move the habitual ways of working into better alignment with the organization’s strategic and operational objectives. These behaviors should be tangible, repeatable, observable, and measurable. They are critical because they will have a significant impact on business performance when exhibited by large numbers of people. They are few because people can remember and change only three to five key behaviors at one time.

Throughout this exercise, you deputize and work with a critical few people (in our Katzenbach Center methodology, and in this article, we call them “authentic informal leaders,” or AILs). You allow and encourage these AILs to function as a “voice of truth,” to help you both diagnose and understand your culture, identify organizational elements that are in conflict with the new formal and informal behaviors, and move your culture toward new ways of working that will amplify what’s best about your culture and business.

Next, you designate teams or areas of the business that make it easy to see how the new behaviors are relevant to the daily work. These teams then identify the organizational elements that cause friction or resistance with the new ways of working. In tackling those conflicting elements, these teams find formal and informal ways to support and enable those new behaviors. At every stage, with discipline and persistence, you create ways to tie these behaviors to tangible business results and to measurable outcomes. The best way to motivate people is to have them see and feel how new behaviors make a vital difference.

Over the course of a frank, three-hour lunch meeting, Sandra’s point of view started to sink in. Andrew understood that he’d been approaching his culture effort far too prescriptively — following a by-the-books approach that lacked emotion, or, as Sandra put it, “soul.” In this second meeting, they considered where the “pockets” of emotional energy in the hotel company might be, toying with the idea of engaging the call centers through which customers made reservations, or the frontline desk staff who checked people in. He pondered, with Sandra, “Where in this company is innovation really happening? What can I do to bring that to the surface, to see more of it?”

You can ask yourself a similar series of questions to discern what actions you should take. Below, we offer four practical ways — based on our principles, work with clients, and research — to close the gulf separating you from your employees.

1. Ground Culture Goals in What’s Possible

Any leader aspiring to transform an organization’s culture must begin with a clear idea of the current state, and must build toward a clear idea of how any shift or modification will support strategic goals. Cultural evolution that isn’t aligned with the strategy and operating model will never take root.

Andrew and Sandra began by brainstorming together: “Let’s start by making a list of what our organization already does well and what our strategic goals are. Then we can figure out which goals are the most important, what traits we will need to get there, and which goals conflict with the culture we are trying to build.” Sandra cited the disconnect between Andrew’s aspiration for a culture that supported innovative ideas and the company’s existing compensation guidelines, which were heavily weighted to encourage employees to follow systems and processes. “If we want people to be OK with fast failure, we can’t use a compensation system that punishes people for wrong bets,” she pointed out.

Too often, leaders don’t begin with this kind of realism. They create a laundry list of the traits and characteristics they aspire to see in their company, and then try to retrofit how people work to fit those goals. But that isn’t how people behave, nor is it how cultures evolve. Some elements in a culture will support a specific strategic play, and others will undermine it.

Consider, for example, a utility company that recently sought to develop a more innovative culture. The leaders thought they could follow the example of technology companies known for their innovation and “borrow” their way of working. But then they recognized how they should and could focus on their own innate strengths, rather than aspire to unrealistic ideals. Technology, as an industry, involves big bets, ruthless experimentation, and audacious goals. A utility that modeled itself along startup culture lines wouldn’t last long — reliability would be compromised, the safety of customers and employees would be at risk, and regulators would surely impose sanctions. This utility would have been better served by looking within to understand the strengths in the culture of its core business, such as a pride in continuous productivity improvement.

2. Use Emotions to Bridge the Gap

Cultural evolution requires connection — between strategy and culture, and between leadership and the rest of the organization. But how can company leaders tighten the link between their aspirations and the concerns of the rest of the organization? By calling on and tuning in to the emotions of the workforce.

It takes intensive listening to understand the cultural reality of an organization. Many leaders find it challenging at first to tap the emotional energy that propels cultural evolution. They are schooled in rational analysis and reasoned persuasion; emotional engagement is out of their comfort zone. But when they can stir a positive emotional response in their people, the AILs — those important influencers of behavior who don’t necessarily have an impressive title — will emerge and help lay the foundation.

Encouraging this type of emotional vulnerability in an organization may be easier than it seems. University of Mannheim psychologist Anna Bruk refers to the “beautiful mess effect”: the tendency people have to view their own vulnerability much more negatively than that of others. Realize that when you show vulnerability as a leader, others see it as a sign of courage, not weakness. Your example will help others understand the beauty of their “messes” as well.

The top leaders of a financial-services firm recently found themselves grappling with this. They had made massive capital investments in improving the technology platform to allow their regional banks to view and understand customer-specific data. After building and rolling out the platform, the firm’s leaders discovered, to their great frustration, that employees in the regional banks were not using the new systems, but instead were relying on older, less capable tools and ways of working. Rightly, the firm’s leaders viewed this resistance as a culture issue.

Interviews and focus groups revealed the source of the resistance. It was a simple human emotion: fear. “The data suggested that we’ve been approaching things in the wrong way, but we don’t feel we have air cover to change our business practices,” the regional banks’ employees reported. “We don’t feel supported when we make mistakes.”

To address the issue, the leaders deployed the beautiful mess effect. They visited the regional banks and spoke frankly, not about what they believed the local sites needed to change, but about their own setbacks and failures. After some initial discomfort, leaders found that sharing their stories aided in creating bonds with their frontline workers, and helped those employees’ fears dissipate.

Emotion-based resistance to change, like the fear in the example above, can stop an initiative in its tracks. Positive emotional energy is imperative because it encourages employees to go above and beyond, regardless of external incentives such as compensation and benefits. Specific strengths that are sources of pride within a company feed this emotional energy, which in turn drives people to work harder toward bettering the organization. The sense of pride that comes from this achievement further fuels emotional energy, motivating people to strive for even further success.

3. Engage with and Empower AILs

The best way to hear the heartbeat of an organization is to tap into its authentic informal leaders. These employees have a ground-level view of how things work. Their intuition makes them invaluable allies. They can help identify the critical few behaviors in a company, and translate those behaviors into concrete ways of working. They also play a valuable role by breaking taboos and accelerating behavior change — making it “go viral” — through a grassroots approach.

Toward the end of their second meeting on the culture initiative, Sandra asked Andrew who else he was speaking with on the matter, and wondered if he had arranged to touch base with the company’s AILs. Andrew confessed that he had mainly stuck with the C-suite and a few HR reps. “It’s really new territory, to be honest, to take advice from someone I don’t know, about my own company,” Andrew said.

“Well,” Sandra replied, “it’s a good time to get comfortable with the uncomfortable, and explore informal networks across the company. Where are the pockets of people who come together of their own initiative? Who organizes picnics? Who are the loudest voices on the intranet? Who do others turn to for advice when there’s a crisis? These are the people you need to engage, to help you design an effort that won’t be met with skepticism and resistance.”

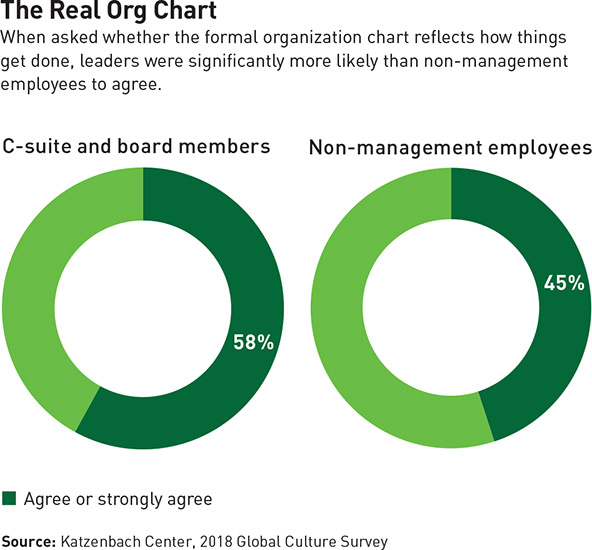

Along those lines, in our survey, we asked about the alignment between the formal and informal ways of working in respondents’ companies. In almost half of the total responses (48 percent), respondents confirmed our belief: The way that work gets done in a company often does not neatly align with the formal organization chart. And when we viewed these results by employee level, we once again saw that gap between how leaders and their people viewed their organization. Fifty-eight percent of C-suite respondents said that the way work got done aligned with the organization chart; only 45 percent of non-management employees agreed (see “The Real Org Chart”). Our experience with clients in a wide range of industries corroborates this finding. Using organizational network analyses, surveys, and interviews, we have found time and again that an informal network of individuals from across the organization exhibits certain leadership traits within their teams or functions, even if they lack formal authority.

Bear in mind that inviting the input of informal leaders can be unsettling. Informal leaders, with their ground-level perspective, are likely to make observations and suggest actions that formal leaders will not — cannot — think of otherwise. What’s more, the informal leaders’ suggestions will often challenge the judgment of formal leaders. That kind of pushback can feel unexpected, even unwelcome. But it can also be the source of powerful ideas.

How can AILs help formal leaders connect their cultural aspirations to the day-to-day working life? First, listen to your AILs’ stories. One major healthcare company organized a network launch event to bring together the organization’s diverse array of informal leaders. As they would with any group of 25 or so people who don’t know one another well, the leaders were concerned about how much people would open up. But when the CEO asked a simple question to kick things off — “What inspires you?” — the responses were numerous and passionate. People shared stories about the sense of pride they took in their work, and how helping others navigate the healthcare system during a difficult time reminded them of their own experiences and challenges. By taking the time to listen to how people contributed to the organization, usually in ways that could not be captured in an organization chart or operating manual, company leaders surfaced the true emotions within the organization, emotions they could tap into to propel change.

4. Model the Behaviors Yourself

In emphasizing the key role of AILs in culture initiatives, we don’t mean to minimize the importance of formal leaders. After all, when a leader’s behavior deviates from the status quo, people take notice. Indeed, you must “walk the walk” and demonstrate the critical few behaviors yourself. Do something right away and make visible, concrete changes to how you work that signal the type of behavior you want to see in others. Find ways to make people feel good about focusing on those behaviors. If formal leaders aren’t in sync with the behaviors that informal leaders are modeling, they run the risk of creating dissonance in evolving their organization’s culture.

With Sandra’s encouragement, Andrew found a way to put himself and his own ego on the line. He heard that a group of coders on the company’s technology team had designed a hackathon, challenging participants to build a new app that could improve the hotel guest experience. Although Andrew had only a rudimentary knowledge of coding, he threw an idea into the ring. His app idea didn’t win, but his willingness to show up and participate — and to acknowledge the talent and expertise of the other competitors and winners — was an important stride toward appealing to the hearts and minds of many in the organization. Sometimes, even a simple change of habit, such as speaking last after a presentation (if you’re normally the first to give input), can change the dynamic in the room and signal that the culture effort is real.

Looking Ahead

All four of these steps make it seem natural to be a culturally conscious leader. They are relatively straightforward ways to get at some very deep relational and emotional issues. When you practice them, you become a role model for the culture you are trying to create.

There is increasing and widespread awareness of the singular contribution of culture to business success. Indeed, culture is having a moment. But beware: Don’t treat culture like the next management buzzword and allow your initiative to come and go without making any authentic organizational change. A culture solidly rooted in a handful of foundational, emotionally resonant truths can transform your organization and unlock its greatest potential.

When leaders follow our guidelines — grounding goals in what’s possible, tuning in to emotions, empowering AILs, and displaying behaviors consistently themselves — they ensure that a focus on culture isn’t just lip service but something real and lasting. That’s the way to lead a successful cultural initiative, and a vibrant, ever-evolving organization.

Gaining Cultural Insight

by Jon Katzenbach, Gretchen Anderson, James Thomas

If you are truly interested in having your company transform — if you genuinely want a high-performance organization with a cadre of people committed to the success of the enterprise — then you need to become conversant with the emotions, behaviors, and deep-seated attitudes that exist in your company. You need to know what employees feel strongly about, both positively and negatively. We call this knowledge cultural insight — it’s the clarity that allows you to truly see what motivates your people. This excerpt from our book The Critical Few demonstrates the kind of dialogue that leads to cultural insight.

Alex, the CEO of a retail company called Intrepid (a fictional composite), has called upon coauthor Jon Katzenbach as an advisor. Although Alex knows that there are pockets of positive emotional energy throughout the organization, he needs help figuring out why Intrepid’s people are resisting the company’s new change initiative. Here’s part of their conversation.

KATZENBACH: The crux of the problem is your cultural situation. What’s holding you back is the way your people feel, think, behave, and relate to one another; in other words, the way they work together. That’s why everybody’s so frustrated — even you. The way you’ve talked about change is vague: “Maybe a reorg. Maybe a few layoffs of redundant staff.” You don’t sound convinced that any decisions you make actually could inspire or catalyze real change.

ALEX: I’ve been there before. I want to be optimistic, but in the back of my mind I know it never works.

KATZENBACH: No, it never does. Or rather, to be more specific, you see a few impulsive responses right away, but you rarely see the kind of sustained results that lead to true transformation. Look, you’re a well-established company. Most of your people have been here a long time. None of them are going to change what they do or how they do it easily. Bad habits persist.

ALEX: So you’re saying I can’t fight culture. What does that mean? Do we just go slowly into oblivion?

KATZENBACH: No. You have to find a way to get important emotional forces in your current culture working with you. It’s a little like jujitsu — you need to use your existing momentum as leverage. In this case, that’s as much emotional as it is rational momentum. I’ve yet to hear you say much about the current positive emotional commitment that many people already have to Intrepid. It has to be there — there is always a reason other than a paycheck that people show up for work every day. Chances are, there are some reservoirs of genuine positive emotional energy lurking somewhere within your current cultural situation that can be harnessed if brought to light.

ALEX: I don’t think it’s possible to make an emotional connection with 10,000 people.

KATZENBACH: Maybe you’re not focusing on the right places or asking the right people. Have you ever really listened to your company’s people down in the lower levels of the hierarchy? Do you know what they care about, why they come to work in the morning? How they describe to their kids what they do for a living? Believe it or not, if you’re ready to hear it, people really will open up to you. And you don’t have to ask everyone — just the people who intuitively understand “how things get done around here.” The best thing you can do, if you want to start a movement, is to empower your people to start solving their own problems — and then get out of the way.

Author profiles:

- DeAnne Aguirre is a leading practitioner in people and organization strategies for Strategy&, PwC's strategy consulting business. Based in San Diego, she is a principal with PwC US. She is the global leader of the firm’s Katzenbach Center, a center of excellence for organizational culture, leadership, and teaming with a network of practitioners around the world. She advises senior executives globally on large transformations and is an expert in organizational effectiveness, culture, leadership, and change.

- Varya Davidson leads PwC’s culture, leadership, and change business for Strategy& in Australia, Southeast Asia, and New Zealand. She is also a member of the Katzenbach Center’s global leadership team representing Asia-Pacific. A partner with PwC Australia, she specializes in strategic transformation and has a passion for people and organization dynamics.

- Carolin Oelschlegel is a director of the Katzenbach Center and led the Center’s 2018 Global Culture Survey. She advises clients around the world on culture and leadership topics and co-leads the Katzenbach Center’s operations. Based in San Francisco, she is a director with PwC US.

- Also contributing to this article from the Katzenbach Center were Gretchen Anderson, a director based in New York; Reid Carpenter, a director based in New York; Alice Zhou, a manager based in Philadelphia; and Varun Bhatnagar, a senior associate based in Dallas.