Pfizer’s vaccine machine

CEO Albert Bourla discusses how a company founded in the 19th century is taking on the biggest health challenges of the 21st century.

This interview is part of the Inside the Mind of the CxO series, which explores a wide range of critical decisions faced by chief executives around the world.

Talk about a pivot. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla was one year into his tenure. Bourla, born and educated in Greece, is a 27-year veteran of the company. A trained veterinarian, he rose through the ranks of its animal health unit, and subsequently held leadership positions responsible for numerous businesses, including vaccines, oncology, and consumer products, before taking the post of chief operating officer in 2018. As he formally took the reins of the company on January 1, 2019, Bourla was focused on continuing Pfizer’s transformation into a pure-play biopharmaceutical company: placing its consumer health business in a joint venture with GlaxoSmithKline in 2019, preparing to spin off the Upjohn unit in a deal with Mylan, and rebranding the more than 170-year-old company to focus on its heritage of making scientific breakthroughs that could aid humanity. A year later, Bourla and Pfizer were intently focused on a COVID-19 vaccine, which the company developed in conjunction with BioNTech. In December 2020, it became the first major COVID-19 vaccine to be approved for emergency use. Bourla sat down (via Zoom) with PwC global health industries leader Ron Chopoorian and strategy+business editor-in-chief Daniel Gross to discuss Pfizer’s strategy, and why he believes the “miracle” of the COVID-19 vaccine was not a result of luck.

S+B: When you embarked on the journey to become a pure-play biopharma focusing on breakthroughs that change patients’ lives, could you have imagined positioning Pfizer to be the first company with an authorized vaccine to fight a global pandemic?

BOURLA: While we couldn’t have imagined the onset of such a devastating pandemic, the point of the transformation of Pfizer was to position the company to be able to provide solutions to situations like these. And to situations that are maybe not as acute but are equally a burden to society, like cancer, other infectious diseases, pain, and rare diseases. All of that required a company that knows how to design a molecule, develop it into a drug, manufacture it, and send it to the patient.

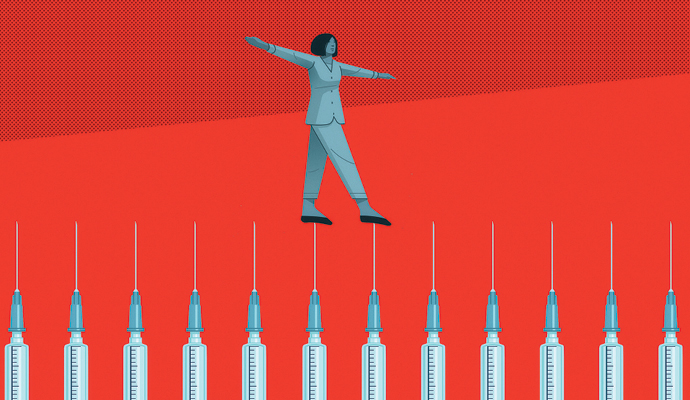

S+B: Delivering the vaccine in a short time frame required operating with maximum speed and urgency, while also not compromising patient safety and scientific rigor. What aspects of the company’s culture enable the balancing of those tensions?

BOURLA: We were able to move faster than biotech companies, faster than companies that are founder-based or backed by venture capital — all of which are known to be able to move very quickly. That’s what makes me prouder than anything else. It was always my dream to be able to build something like that. And that started back when we reorganized the business and made it clear that everyone needs to deliver outcomes if they want resources. I used to tell people that “you are here to compete for resources. I will give you the money for your proposals. Make sure that you bring me proposals that are going to bring us medicines that significantly improve the current standard of care, and that can provide a significant impact, even if there are small populations of patients involved.” This is exactly how it worked. Our chief scientific officer, chief development officer, and the global head of vaccine research came up with the idea of working with BioNTech and approved it. They did it. Not me. And that’s because we already had the experience of working for several years under this decentralized approach.

S+B: Pfizer’s purpose revolves around a series of bold moves and big ideas. And it explicitly places a high value on large and open-ended attributes like courage, excellence, equity, and joy. How do those play out in the context of a pharmaceuticals company?

BOURLA: We all agreed that the transformation we were driving would only succeed if we had the right culture, and it had to be particular to Pfizer. You can’t simply go to Harvard and the best business schools and ask: “Which company has the best culture, so we can copy it?” The winning cultures always should be tailored to the specific needs of the industry in which the company operates, and to the specific moment — and I don’t mean a specific year. What are the challenges and opportunities ahead in the next decade? And you also have to take into account the heritage of the company.

When we spoke about courage as a very big part of our culture, we meant clearly that we need to think big. If something is not going in the right direction, speak up. When we spoke about excellence, it was very clear that it was about excellence in execution. Equity was likely one of the least understood parts of our culture at the time. Now it is very much understood. We have deep in our DNA the principle that everybody deserves to be seen, heard, and cared for; it’s not about the rich countries and poor countries; it’s not about American or Canadian or European or Middle Eastern countries. It is about how to make sure that you provide access to all. And then there’s joy. We take our work very seriously, but we also find great joy in delivering breakthroughs that change patients’ lives.

S+B: The world was waiting for Phase I, Phase II, Phase III results, for FDA review. Was that a challenge, to balance the urgency with the need to go through the right protocols and maintain what the science and process tell you has to be done?

BOURLA: No. We have been in existence for more than 170 years. It was clear to us that we — our people — need to demonstrate that this is a safe and effective vaccine. We are not going to jeopardize this legacy of trust in the Pfizer brand. And we also made it very clear that we will follow regulators’ advice no matter what. Then the question was, how, within these boundaries, can we do things differently and faster? That was the challenge. And indeed, people did things very, very, very differently.

S+B: This was all done in a world in which many people were having to work remotely for the first time. For an enterprise as collaborative as pharmaceutical research and trials, I would imagine that not being able to meet freely with colleagues would present significant challenges.

BOURLA: It’s clear not only to me but to everyone else who’s running a business — actually for every organization in the world — that this was a gigantic experiment that has been proven quite successful in terms of improving productivity. If someone had come into my office last February and said, “I have an idea. Why don’t we keep everybody working from home and see what’s going to happen?” I would have kicked him or her out immediately. I would have said, “You’re crazy.”

I think it was a miracle in the sense that the chances of being successful were so, so slim, and we were overwhelmingly successful. But I want to make something very, very clear. That was not luck. That was very deliberate.”

Suddenly, you’re forced to do it, and then you realize that actually, it works very well. People liked it. I’m sure that people are very tired right now. But it’s not because they don’t go to the office. They’re so tired because they can’t go out of their homes, because they can’t see their parents and friends. But the fact that they don’t have to commute one or two hours, or three in many cases, I don’t think that is bothering people that much.

In-person contact with colleagues is very important. But it doesn’t have to be on a daily basis when you have opportunities with technology to almost replicate the experience. Now, everybody needs to find their own recipe, and some will be more successful than others. And we’ll learn from that and transition into the new working situation.

S+B: How has this changed the way you lead an organization of this size?

BOURLA: There’s no doubt that I did things very differently, and I learned also how to work remotely. But in my case — and for Pfizer people in general — because of our contribution to the pandemic response, the remote part of working was the least developmental aspect of everything that happened. To find yourself leading the company that is leading the race for a vaccine that is the hope of billions of people, of millions of businesses, hundreds of governments — that, by itself, puts so much weight on your shoulders. You need to develop your leadership skills in a very different way. You have to be able to navigate the political minefield, the elections in the U.S., and the conversations with political leaders around the world. This was only my second year as CEO. And it clearly gave me an opportunity to grow.

S+B: Once the pandemic is under control, do you think there will be a snapback to work like it was before 2020?

BOURLA: Our intention is to have a very flexible working arrangement, but not 100 percent remote. We will maintain our offices and our headquarters so that people can have a place they can go. It is very important for the spirit of the culture to create the essential feeling of belonging. But we don’t have to be in an office every day. The expectation for supervisors and workers is that they can do it two days per week, maybe three. And leadership will do the same, to make sure we are showing the way. This means that, of course, we’ll create a different working environment. If you’re only coming to the office a couple times a week, you’re not coming to close the door to your office; you can do that at home. You come so that you can interact with others.

One of the reasons our use of technology was successful — whether it was Zoom, or Webex, or Microsoft Teams — was because everybody was on camera. And if you compare those with the times when there were 10 people in the meeting room and one was connecting remotely, that person felt completely excluded. But once everybody was on equal footing, that issue immediately was resolved. That taught us something. So we may design meeting rooms differently. Maybe everyone sitting there will have a screen in front of them.

S+B: Given the skepticism among what seems to be a significant chunk of the population to take the COVID-19 vaccine, what do you think are the most effective ways that governments and businesses can encourage them?

BOURLA: Let me start with an assessment of the situation. There were a significant number of people who were skeptical. That number is going down, for multiple reasons. First, this vaccine has been approved by multiple authorities around the world.

Second, I don’t blame people who were very skeptical, because that was a very confusing period. And it became a political issue, just like wearing a mask. Complete nonsense, right? The mask is about protecting people. The same holds for the vaccine. That’s why you have a vibrant industry like ours that can rise to the occasion and bring solutions. But it’s also why you have supervision like regulatory agencies, to make sure that things are happening appropriately.

We have seen examples of countries creating incentives for people to get vaccinated that are very successful. Like, if you’re vaccinated, you’re free to travel outside the country and come back without isolation, for example. Clearly, I don’t think it will give us any benefit to try to create restrictions and tell people: “You have to do it, otherwise there’s a punishment,” because it’s a new vaccine. I think people need to see some more data of how many of those who are getting the vaccine are protected in real life and how many of those who don’t are getting sick and dying in real life.

So let’s focus on getting as many people as possible vaccinated and generate data that will convince even the most skeptical. And then, instead of forcing people, we need to educate them. At the end there will be some who will continue to be skeptical. There’s a tendency to see this with all vaccines. We have to teach people that the decision not to take it isn’t a decision that will affect only themselves. It is a decision that will affect society. It will affect the people they love the most — their mother and father, for example. So if you don’t take the vaccine, you’re becoming the weak link that allows the virus to replicate.

This is my father-in-law, the 1st member of our family to receive his 1st dose of the vaccine. At 84, he is high-risk & graciously waited his turn in Greece. I've heard many stories from people filled w/ emotion at seeing their loved ones get vaccinated. Now, I know the feeling. pic.twitter.com/oTSdtB3HZp

— AlbertBourla (@AlbertBourla) January 25, 2021

Bourla took to Twitter to share the news of a family member receiving the vaccine in late January.

S+B: One of the effects of the pandemic in so many industries has been to pull the future forward. In medicine more broadly, we’ve seen telehealth and digitization pick up pace. Does Pfizer have to think differently now about how it advertises, how it markets?

BOURLA: Clearly, the answer is yes. We are doing experiments right now with our sales reps, the same way that we are doing experiments with COVID vaccines. We have a placebo group and another group. Some reps are implementing new digital approaches, and then others are implementing the traditional approaches, 100 on each side. And we are measuring to see the satisfaction of the physicians and the satisfaction of the hospital units. And we will continue to experiment. The personal relationship and trust between a medical representative and a physician or hospital is extremely important. But I think we can use digital tools to do a much better job in communicating this information.

And we have the example of accomplishing miracles by doing things very differently, as we did with COVID-19. So the question becomes, why only COVID? Why not cancer? Why not Duchenne muscular dystrophy? And this is exactly what we are doing now.

S+B: You just used the word miracle to describe the vaccine development. Pfizer and others in the industry are constantly developing treatments for all sorts of conditions. Should we characterize what happened in the past year as a miracle?

BOURLA: I think it was a miracle in the sense that the chances of being successful were so, so slim, and we were overwhelmingly successful. But I want to make something very, very clear. That was not luck. That was very deliberate. It was the result of hundreds of decisions that had to be made along the way. And you needed the supervision and passion and dedication from everyone involved. We were successful, not lucky.

S+B: Pfizer has undergone a transformation in the last few years, with several significant transactions. What’s next for the new Pfizer, if you look out over the next five years?

BOURLA: We need to consolidate the changes and make sure that we deliver on our purpose. We need to bring more breakthroughs that save patients’ lives. COVID was just one example. There are so many things that are happening right now in metabolic disease, in cardiovascular disease, in infectious diseases, in rare diseases, in cancer. People here are very inspired by what’s happened with their vaccine colleagues. All of them are high achievers. All of them want to be in the position to deliver a breakthrough that evokes the same sense of gratification that the whole world gave to their colleagues in vaccines.

So that is an unstoppable power, I believe. If we do that, we will find so many other advancements in the other fields, which will help us greatly as we strive to achieve the target we have set of bringing 25 breakthroughs by 2025. But we need to stay the course. I think we need to continue being courageous. We need to have excellence in execution. We need to have the pride of what we do in society be the driving force for the work. That’s part of the joy that we have as a culture.

S+B: Recently, you introduced a new logo, replacing the pill with the double helix. What drove you to change this image that has defined the company for 70 years?

BOURLA: We started this effort to change the logo before the pandemic. The idea, as we were transforming Pfizer, was to imagine a company that was more singularly focused on science rather than a larger conglomerate of multiple businesses. Symbolically, we wanted to maintain our connectivity with our glorious history. So we didn’t change the fonts for Pfizer. But we liberated Pfizer, symbolically, from the pill, and then added this double helix that I think symbolizes two things. One, of course, is the high-end science that the DNA helix calls to mind. But also it represents the patient and the company. This is like two hands that are embraced.

S+B: Is this a moment both for Pfizer and the broader pharmaceutical industry to change or improve the image of the industry and the role it plays in society? Or do you feel like you should just let the molecules do the talking for you?

BOURLA: No, no, not at all. I think we should lead the conversation. And I believe that COVID is a catalyst that created tremendous goodwill for this industry. The industry improved significantly in terms of reputation in Gallup polls, and Pfizer has improved even more. But I think declaring a win right now is the last thing we should do. There is nothing certain about maintaining a good reputation. And if we go back to the old communication practices, we will damage it. We should make sure that we continue demonstrating with words and acts that we are a patient-centric, science-based industry, and that the world needs us. Society needs us. And we will do that by bringing treatments that change people’s hearts, and by isolating the bad actors in the industry.

S+B: Given the tremendous toll in human life and health that was taken while the vaccines were being developed, do you think that there are opportunities to speed up the trial testing period?

BOURLA: It’s clear that we learned a lot of things regarding how to do things differently, like doing more stages in parallel rather than sequentially. We learned how to better appreciate risk. We learned how to use digital. There was a big focus in 2018 and 2019 on digitizing our R&D process. So when the COVID-19 study was about to start, we had already built an infrastructure that would allow us to do a study that was much, much bigger than those we had done previously. For the first time, we used this new system from the beginning all the way to the end. This was a gigantic study with eventually 46,500 people and more than 150 research centers. The scientists could go in every six hours to simulate the situation with high accuracy in terms of data all around the world. There were billions of entries, because so many tests were run and had to be included into this system. Yet there was very little paper to move. So that helped a lot.

S+B: If 2020 taught us anything, it is the futility of forecasting. So how do you personally approach forecasting in an environment like this?

BOURLA: I know very well that all forecasts in the mid-term and long term are very questionable. The way that I approach it is by doing scenario-planning and developing an organization that has the agility to adjust to different situations. If you try to build a very accurate forecast and prepare an organization that will be bulletproof for this one forecast, it’s likely you will fail. You need to do scenario-planning. You need to have leading indicators that tell you which scenario is the most likely to materialize. And you need to be ready to know where you need to go if things go one way or another, and then monitor.

S+B: How do you plan to harness data and analytics to understand the impact of the vaccine?

BOURLA: We can build a very extensive network around the world that is surveying not only the success of our vaccine but also new mutations, and how they behave, and how our vaccine responds to them. Pretty soon, most health authorities will start generating data about how the different vaccines are behaving in real time, in the real world. This morning, I was reviewing data from Israel. The country is a good model because it has a relatively small population and strong medical capabilities, and 99.5 percent of the population has digital medical records. We signed an agreement with Israel so that we can access the information. We are going to make joint publications so the world will see the impact that a vaccination program can have on health and the economy.

Author profiles:

- Ron Chopoorian is the global health industries leader for PwC. Based in New York, he is a partner with PwC US.

- Daniel Gross is editor-in-chief of strategy+business.