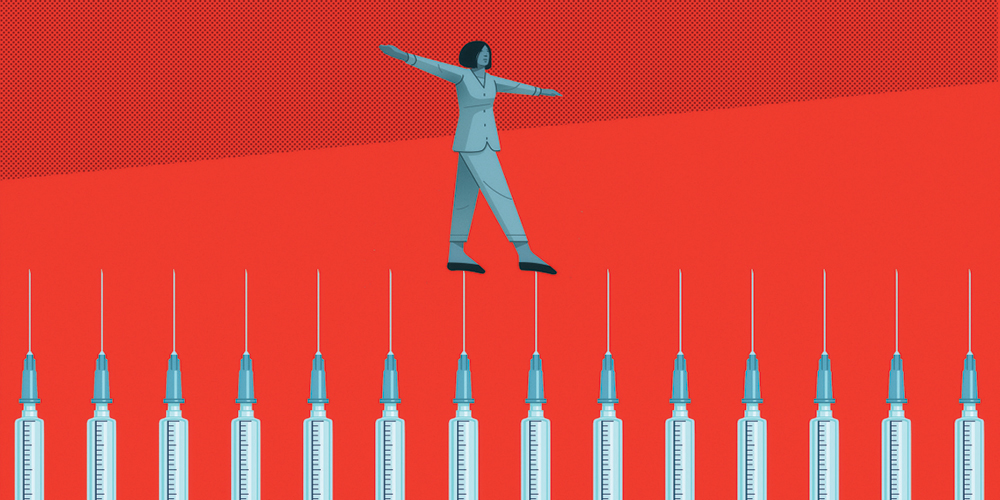

Weighing the risk ethics of requiring vaccinations

Creating safe workplaces while respecting employees’ concerns and choices presents challenges for company leaders.

A version of this article appeared in the Autumn 2021 issue of strategy+business.

As the world continues to struggle with highly contagious strains of COVID-19, businesses are grappling with a thorny question: Should they require employees to get the vaccine? The travel and event industries, tourism-dependent countries, and universities have quickly embraced requiring proof of vaccination for boarding transportation and crossing borders, attending events, and returning to campuses. National, state, and local governments are piloting “vaccine passports,” documents that would prove one’s status.

These new developments raise a tough set of practical and business strategy questions that go far beyond the distribution and efficacy of the vaccines themselves. They involve legal, human resources, governance, social impact, and reputational risks — and ethics. Indeed, the arrival of the vaccines can be a catalyst for valuable dialogue about how risk-taking and ethics play into an organization’s culture. By analyzing how leaders and employees feel about different kinds of risks and what they are willing to tolerate, companies can assess how cohesive their teams are. They can also better understand employees’ likelihood of taking “good” risks by innovating and pursuing opportunities, or, conversely, creating “bad” risks that could hurt the company’s reputation and financial health.

Acceptable risks

David Rodin, a moral philosopher and founder of Principia, a business ethics advisory firm, points out that all societies accept some risks because the benefits outweigh the potential harm. It’s why people tend not to have a problem with speeding ambulances. The same principle applies to vaccines.

At the same time, institutions, like societies, must justify their decisions about which risks to accept and which actions they take. That requires having an open, transparent conversation and creating meaningful consent based on the best information possible. “One of the basic principles of consent is that it has to be properly informed,” Rodin told me. “So if people do not understand sufficiently the nature of the risk, then the consent is meaningless.”

In a recent ethics briefing, Principia laid out a vaccine policy framework that starts with mapping considerations that vary widely by location, such as vaccine availability, infection rates, and other risk factors.

If vaccine doses are not readily available, for example, a company will have a hard time requiring vaccination unless they provide it on-site. Or a location with low infection rates may get more pushback if it mandates vaccines.

Decision-making is also influenced by the type of company making the judgment. A customer-facing business bears the risk of infecting clients as well as employees, whereas a knowledge business whose employees can work remotely confronts a much easier set of choices. “Organizations with a clear necessity to promote public health and the protection of the workforce — such as healthcare providers, for example, or in settings with exposure to vulnerable people — may see a need to mandate vaccination except in cases of medical or religious exemption,” the Principia team wrote.

Principia recommends that companies openly consider trade-offs involving duty of care, individual autonomy, and fairness. The top duty of care is an extremely important priority: to provide a workplace that is safe for employees and those with whom they come into contact. Individual autonomy includes the personal decisions to receive a vaccine or to accept the risk of being exposed to unvaccinated people. Questions of fairness can be complex, as they are tied both to vaccine access and to employees’ perceptions of the risks of getting vaccinated or not.

Motivation matters

Although understanding the nature of a risk is crucial to making an ethical decision, it is equally important to listen to why employees feel the way they do about whether to get vaccinated.

Employees who refuse vaccination because they simply don’t want to make the effort, or selfishly decide to free-ride while others contribute to the goal of reaching herd immunity, should raise a red flag. If they express those attitudes in other contexts, they could put fellow employees or the company itself at risk.

Other motivations are more complicated. Some people worry that vaccine approval was rushed. Some members of minority groups are understandably fearful based in past bad experiences with the healthcare system. Others have valid medical or religious reasons.

Researchers at the University of California–Irvine found that when people are more likely, as individuals, to approve of the reasons for taking a risk, they tend to regard the activity in question as being less risky. In the same vein, employees who feel that their peers have good reasons for hesitating to be vaccinated are more likely to perceive the increased risks to themselves as being lower than if they feel their peers are being selfish and unethical.

Company decisions about whether to require employees to be vaccinated are further complicated by the fact that public opinion remains polarized over requiring proof of vaccination, with stratification by age, nationality, and education level. What’s more, support varies depending on the activity. Roughly three-quarters of respondents to a recent Ipsos/World Economic Forum survey favored requiring vaccine passports for travel. The survey was conducted between March 26 and April 9, 2021, among more than 21,000 adults in 28 countries. For activities other than travel, support for requiring proof of vaccination fell off fairly quickly. Around two-thirds approved of requiring vaccines for those attending large events. But only half thought proof of vaccination should be required for restaurants, stores, and the office.

A broader risk conversation

The specifics of the vaccination conversation are part of a much broader, evolving debate about the appropriate role of risk ethics in business. Until recently, ethics has mainly taken a back seat to potential liability, or downside risk: in this case, whether a company can be fined or sued either for forcing people to be vaccinated or for putting employees and customers at risk if they get sick because the company has not kept them safe.

But there is a powerful case to be made for paying attention to risk ethics. When you do, you can seize a potential opportunity to be seen as ethical — that is, if the public sees the company’s behavior as authentic and not merely posturing. “We’re finally at the point we need to start having a different conversation about ethics, rather than just reputational or regulatory risk,” said Alison Taylor, executive director of Ethical Systems, a research center based at New York University.

Having a completely vaccinated workforce (with exceptions for those with medical conditions that prevent them from being vaccinated) — and getting there via an open, informed, and ethical conversation — is a way to create the safest possible environment for employees and customers. In turn, that can build stakeholder trust and a strategic reputational advantage that can be helpful when it comes to recruiting employees, building brand loyalty, and reducing reputational risk.

“Reputation has never been so high as a driver of value,” Taylor said. “This puts a premium on stakeholder trust and means that if you do get this right, there is considerable upside.” The numbers back her up. The value of intangible assets — things such as reputation, brand value, or R&D — has risen dramatically since the 1980s. By one measure, intangibles hit a record level of US$21 trillion in 2018, or an astonishing 84 percent of all enterprise value on the S&P 500. By comparison, this ratio was just 17 percent in 1975.

Carrots or sticks?

When it comes to vaccine mandates, immediate practical concerns are taking precedence. Most businesses are unlikely to be able to force their employees to get vaccinated, for both ethical and legal reasons. Nor will they be able to insist that other employees work in close physical proximity with people who refuse the vaccine. And that’s before they factor in healthcare privacy issues.

The question then becomes how much accommodation to make for people who still refuse. The accompanying ethics calculations differ depending on a person’s reasons for not getting vaccinated and the amount of in-person contact that a job requires. If people are hesitating because they don’t have accurate information or have trouble getting a vaccine, the ethical response is to give them that information and easier access. For those with a legitimate medical or religious reason, or who can easily work from home, the situations require more flexibility.

If people are hesitating because they don’t have accurate information or have trouble getting a vaccine, the ethical response is to give them that information and easier access.

Several health providers already have announced that they will require vaccines. And an ASU/Rockefeller Foundation Survey of U.S. and U.K. employees undertaken this spring found that 59 percent of employers plan to incentivize their employees to be vaccinated, and 60 percent will require proof of vaccination from employees.

The carrots companies are offering include paid time off for people to get their shots. Some companies are arranging vaccinations on-site. Other incentives include free transportation to vaccine sites and cash bonuses for getting fully vaccinated.

As for the sticks, 42 percent of the businesses who responded said they would not allow employees who don’t get vaccinated to come on site, and 35 percent said that they would consider discipline against the unvaccinated, including possible termination.

Companies also may get help from outside players that are wielding sticks (and a few with carrots such as free beer, donuts, and sports tickets). Governments, airlines, and event companies increasingly require proof of vaccination to travel or attend large gatherings such as conferences or concerts. It’s possible that such external requirements may convince some vaccine-hesitant individuals to change their mind. A salesperson working for a company that doesn’t require a vaccine may discover they can’t travel to a vital trade show without proof of vaccination.

Whatever they decide, companies should not pass up the opportunity that the vaccine debate has created to catalyze an important conversation about risk and ethics. By making their vaccine decisions through an open and transparent process, leaders can gain new insights into their firm’s risk culture and ethical attitudes, which are at the heart of an organization’s purpose and mission, its ability to innovate and change, and its reputation and brand.