The Right Ideas in All the Wrong Places

How strategic intuition unlocks innovative solutions to your biggest problems.

This article was written with Nadim Yacteen.

What do the Dodge Dart Registry, Facebook, Old Spice deodorant, and Restoration Hardware have to do with the future of banking? All four contain seeds of a strategic innovation urgently needed in that industry: lowering the cost of retail distribution while improving the customer experience for an increasingly complex range of consumers (from old to young, urban to rural, wealthy to poor, tech savvy to technophobic, and so on).

We’ll explain more below, but for the moment, let’s focus on the bigger picture: Challenges as daunting as the one faced by bankers exist in almost every industry, owing to the new competitive forces and profitability pressures unleashed by globalization, digitization, and postrecession anemia. It’s why most executives are seeking more strategic innovation from their organizations. They want ideas that are big and proven. True strategic challenges will not be conquered with incremental solutions, and corporate life is already too risky to bet on a big idea that may or may not work.

Which brings us to the question of the day: Where do big, practical ideas come from?

In 2000, Eric Kandel won the Nobel Prize for showing how humans produce a new thought. He demonstrated that the right side of our brain is just as analytical and logical as the left, and the left side is just as creative and intuitive as the right. Thus, when it comes to innovation, the whole brain is involved. Kandel’s work also shows the human brain to be the greatest inventory system on earth. From birth, your brain takes in stimuli, breaks them down, and then stores them on “memory shelves,” which are distributed throughout your brain. When presented with a particular challenge, your brain searches to see if there is any connection with what is already sitting on your memory shelves. When your brain finds a match, your memories combine with new stimuli and you experience “Eureka!”—a novel thought that feels like a flash of insight.

This brings us to Columbia Business School professor William Duggan, who discovered an amazing parallel between how strategic innovation happens and Kandel’s model of how the mind works. Consider two examples, one old and one new:

- Henry Ford was looking for ways to improve the productivity of fixed assembly lines (where the cars are stationary and workers move from car to car), when one of his employees wandered into a Chicago slaughterhouse and observed that pig carcasses were hung on a line that rotated from one stationary butcher to the next until the pigs were fully disassembled. Eureka! Thus was born the first moving assembly line—a profound innovation that changed manufacturing forever.

- Reed Hastings’s inspiration for Netflix sprang from combining four seemingly unconnected experiences sitting in his memory banks: the $40 fee charged by Blockbuster when he was late in returning Apollo 13; the monthly membership dues from his local gym; his experience with Amazon’s Web-based ordering features; and a conversation with a friend who told him about the DVD, a new technology from Japan that was far less bulky than the videocassettes at Blockbuster.

These examples show that it’s not immaculate conception or miraculous deduction that produces strategic innovation. These breakthroughs emerged from neither the ether nor traditional brainstorming. And they certainly did not evolve from typical approaches to strategic planning or product innovation. Each arose from its originator’s “strategic intuition” (a term coined by Duggan): Ford and Hastings made seemingly random connections between things sitting in plain sight—for anyone to see—to crack a particular strategic challenge.

When one sees words like “intuition” and “random connections,” it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that innovation is largely based on individual brilliance and luck, and that Kandel and Duggan’s theories argue against the idea that companies can take any kind of systemic approach to creating truly novel strategic innovation. But, in fact, these theories help unlock the secret to building an entirely new way for companies to bring greater innovation to their strategies. The solution has three parts.

The first is so obvious that most companies miss it: You must have a specific strategic challenge in mind. And it has to be the right one—one that demands true innovation because it’s a problem with no apparent solution. For online retailers, this might be how to increase their share of customers’ weekly groceries, the category least penetrated by these companies. In the pharmaceutical industry, it could be a reinvention of the product launch model, which has failed to keep pace with the many changes in its market. As Henry Ford once said, “The air is full of ideas. They are knocking you in the head all the time. You only have to know what you want, then forget it, and go about business. Suddenly, the idea will come through. It was there all the time.” He understood that you have to know what you are looking to solve in order to find the innovation to solve it.

Problem in hand, you begin your search for possible solutions by answering this question: For each part of the challenge, who else—anywhere, anytime—has solved a piece of the puzzle? The objective is to create the largest possible inventory of precedents that are relevant to solving the challenge. We call this your “What Works Inventory.” The bigger and better the list, the more likely it is that it will contain the critical set of dots that can be connected to produce a breakthrough innovation. Our opening question cites four precedents that are relevant to solving the retail distribution challenge for banks: The Dodge Dart Registry yields a clue to how banks can engage consumers in financing their milestone purchases; Facebook suggests ways for banks to become a welcome hub of consumers’ financial lives; Old Spice shows how a stodgy brand can earn new equity with the next generation; and Restoration Hardware’s drive to reduce its retail footprint by 30 percent while repurposing most of its remaining properties into showrooms and design galleries sparks thinking on what banks could do with their high-cost retail branches. It is essential to look outside your normal domain. If your challenge is a rapidly changing business ecosystem, look at how other species—in the business and natural world—survive and thrive when their ecosystems are disrupted. If your challenge is to simplify the selling of multiple drugs for the treatment of diabetes, look at how www.Mint.com simplifies the selling of financial services. One thing is certain: You will not find true strategic innovation by looking at best practices inside your own industry. Nor will you find it by looking for simple analogs that take your strategic challenge as an indivisible whole. Which brings us to the third part.

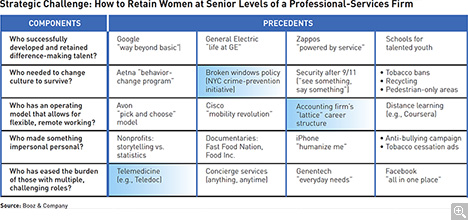

You now need to engage in what we call “intelligent recombination.” Start by putting together a table of precedents from your What Works Inventory that offers a range of proven solutions for each piece of the puzzle that is your strategic challenge. We call this your Insight Matrix (a Duggan term borrowed from General Electric’s famous “Work-Out” process), where the first column lists components of the strategic challenge that must be addressed and the rows display a series of companies and precedents that apply to those components. The exhibit below shows the Insight Matrix developed for a strategic challenge faced by many professional-services firms: how to retain more women in their senior ranks.

Now you are ready for the “creative” part. “Creativity is just connecting things,” Steve Jobs said. “When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while.” In our context, this means looking for connections between precedents in your Insight Matrix to find a breakthrough idea—the “Eureka!” that solves the problem of your strategic challenge. For example, to address the challenge of retaining woman, one firm developed a solution by combining elements of these three discrete precedents: (1) the broken windows theory of focusing on smaller tasks to create a larger impact; (2) an accounting firm’s “latticed” career structure that gave women a wider range of options than just climbing the corporate ladder; and (3) the model of remote consultation pioneered in telemedicine.

For intelligent recombination to happen, you must generate conditions where the mind can relax, deal calmly with problems, wander freely, and make new connections, rather than looking for quick answers because you are stressed or time-constrained. When we ask people where they get their best ideas, we rarely hear “at my desk,” “in a meeting,” or “in a brainstorming session.” More common answers are while running, swimming, commuting, showering, cooking, sewing, or doing yard work. Einstein rhetorically asked, “Why is it I always get my best ideas while shaving?” He knew instinctively that when your brain relaxes, it’s able to utilize its natural approach to innovating. Sometimes you should even drop the problem completely. This is why Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—a deeply inventive man who understood the creative process—frequently had Sherlock Holmes drag Watson off to a concert right in the middle of a case.

Capable strategists must embrace and enhance their strategic intuition to generate groundbreaking ideas that successfully address the toughest challenges where their companies most need to innovate. But it’s not easy. The challenges themselves can be difficult to frame in the right way and break down into the right components. The process often involves messy, frustrating iteration. And creating the presence of mind and circumstances to activate your unconscious self is no easy discipline. Thomas Edison’s famous line that “invention is 10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration” is often interpreted as meaning the hard part comes after the easy part. A better interpretation is that a lot of perspiration must go into generating the inspiration that produces a truly breakthrough—and practical—invention.

Author profiles:

- Ken Favaro is a senior partner with Booz & Company based in New York and global head of the firm’s enterprise strategy practice.

- Nadim Yacteen is a senior executive advisor based in New York who leads Booz & Company’s strategic intuition practice.