At Most Tech Firms, the C-Suite Is Still a Boy’s Club

As firms pledge to develop leaders, are they getting ahead of the issue or merely keeping pace?

Each year as March 8, International Women’s Day, draws near, I like to take stock of developments in women’s leadership over the past 12 months. This year, I’m struck by how often I hear companies talk about “spending to stay flat.” In other words, organizations are devoting resources to programs aimed at attracting and retaining women with leadership potential, only to see them leave prematurely, pull themselves off the leadership track, or not progress as quickly—or as high on the executive track—as the organization had hoped.

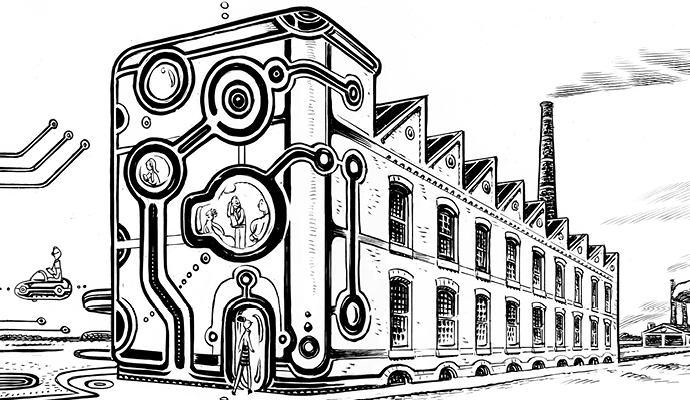

This concern is especially evident in the so-called STEM fields–– science, technology, engineering, and math–– in which women and minorities remain significantly underrepresented. But it’s also true in law firms and other partnership organizations, which continue to see a sharp difference between the number of women hired and the number that make it to partner.

Intel president Renee James gave a megaphone to this concern at January’s Consumer Electronics Show. Sharing her frustration with the “flat” narrative, James announced that Intel would be allocating an unprecedented US$300 million toward the recruitment, development, and retention of women engineers and other tech professionals. Committing this kind of money to address a problem more often met with fiscal band-aids could be a game changer. It’s certainly evidence that the company sees underrepresentation of women as a strategic challenge.

As one who has both worked in and observed the field of women’s leadership for more than 25 years, I believe the key consideration here is how the money will be spent. We know the figure, but we don’t know the specifics. James has been instrumental in the creation of a women’s network at Intel, but these days almost every global company has one. She talks about the need for robust mentoring programs, another important piece of the effort that many companies have been focusing on for the last decade. She speaks of seriously enriching the pipeline of women engineers by collaborating with educators and developing resources in underserved areas. This is a worthy undertaking that can clearly help expand the universe of hirable talent, but doesn’t necessarily guarantee women will make it to the top in anything resembling representative numbers.

I’m not questioning the effectiveness of these types of efforts, which have helped many companies expand their female talent pool and thus create more potential candidates for top leadership positions. But the fact remains that, with a few very high-profile exceptions, the number of women in top leadership positions has been stagnant in recent years has been stagnant in recent years, increasing by less than 1 percent in the S&P 500 since 2009. So if you’re interested in increasing the total number of women in corporate America, programs such as Intel’s seem to be effective. But if your goal is to get more women into senior executive slots where they can have a strategic impact on major decisions, the evidence is less persuasive.

With a few high-profile exceptions, the number of women in leadership positions has been stagnant.

The question is why so many well-intentioned programs aren’t achieving strong results. The culture at many workplaces is clearly one factor—and likely the largest. Supportive mentoring programs and women’s networks can only do so much if the larger culture remains one that women find alienating and unrewarding. Examples include:

• Testosterone-fueled cultures in which long hours are considered the primary sign of commitment

• Companies that claim to value teamwork but base financial rewards on individual results

• Up-or-out workplace cultures or those with rigid policies linking ages to career stages, which may be out of sync with women’s most productive working years

• Beliefs about leadership styles that undervalue traits shown by research to be more commonly found in women, such as inclusive decision-making, fostering consensus, and people development

• Higher compensation for those who land new clients than for those who serve existing customers and clients

These are pervasive issues that no diversity effort to support female employees can overcome, regardless of how well they’re funded.

When it comes to culture, the “shadow of a leader” is a powerful force, which means that even laudatory efforts can be undermined by men who don’t believe that their company is serious or who imagine that their off-the-cuff ramblings and generalizations won’t have a lasting impact on female morale. I remember one woman at a major consulting firm describing its new women’s initiative: “As usual, it’s all about ‘fixing’ the women. The fact that a few—and I emphasize a few—of the men are having an outsized effect on women feeling undervalued isn’t seen as part of the problem.”

What I see missing in the majority of comprehensive women’s programs are a serious effort to identify cultural and structural barriers to women’s advancement and a commitment to helping senior leaders recognize how their own unconscious assumptions may undermine their support for women. When that happens, the message gets heard loud and clear down the chain of command, giving a green light to all kinds of problematic behavior.

Real transformation challenges everyone to take a good, hard look at his or her presumptions. The integration of one-half of the human race into decision-making roles is a massive social and economic undertaking, and men, as much as women, need help in making the shift. If Intel recognizes this, its efforts may finally bring lasting change to the whole tech sector.