Why cryptocurrency’s not quite ready for takeoff

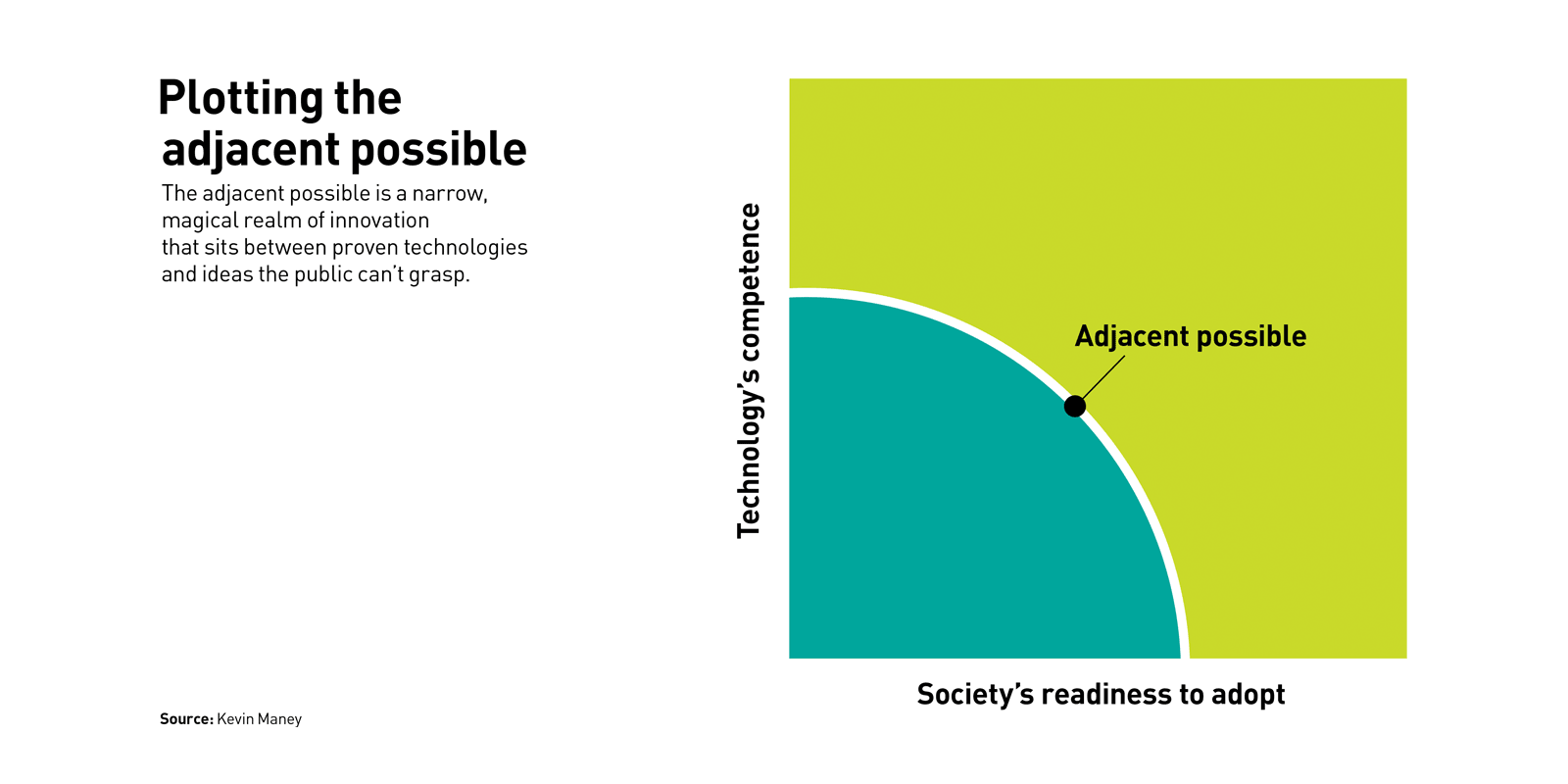

There’s an innovative sweet spot known as the “adjacent possible” that new technologies need to hit before they can soar.

Most of us don’t think cryptocurrency is very pragmatic. Even the adorable crypto-based cats in the game CryptoKitties failed to drag bitcoin and other such currencies into that zone where a new technology catches on and changes the world.

Why? Because crypto remains too far outside of what’s known as the “adjacent possible.”

I first encountered the concept of the adjacent possible in Steven Johnson’s book Where Good Ideas Come From. As Johnson describes it, the adjacent possible is a narrow, magical realm of innovation that sits between the space occupied by proven technologies and the space populated by ideas that are too far out. It’s where you find innovations that aren’t yet possible, but are hovering right next to possible, thus the term adjacent possible.

But Johnson also suggests that innovation is slowly cultivated — not achieved in a lightbulb moment. So, crypto’s time could be coming. And the businesses that can read the signals that a technology is approaching the adjacent possible will be the ones that get to the launchpad at the right time.

The adjacent possible can be illustrated using a coordinate graph. A point on the vertical axis shows how competent the technology is today, and a point on the horizontal axis shows how ready society is to accept and adopt the technology. The curve that connects the two points constantly moves outward over time, as technology gets better and society embraces new innovations. Inside the curve is technology that exists and is accepted. TVs, smartphones, and airliners are all safely inside this zone. Outside the curve is what’s not yet possible or adopted. Either the technology isn’t good enough yet, or the public isn’t ready — or, more typically, both. Holographic entertainment, augmented reality glasses, and consumer space travel sit out in that zone. Build such a product, and it will be too far ahead of its time.

The magic happens in the thin band separating the two zones — in the adjacent possible.

Johnson argues that all great innovations take off in the adjacent possible, and that a key factor in hitting this sweet spot is that solutions and sentiments that support the new technology are already well-developed so all it takes to bump a technology over the line is the discovery or creation of a certain missing piece. For example, when the Wright brothers first flew in 1903, all the mechanics and theories necessary — from the piston engine to wing aerodynamics — already existed.

A key factor in hitting this sweet spot is that solutions and sentiments that support the new technology are already well-developed so all it takes to bump a technology over the line is the discovery of a certain missing piece.

The Wrights just had to push the technology a bit further by putting the right parts together and adding some key insights of their own. By that point, too, early cars were on roads and inventors had been trying for years to fly, so the public was ready to believe a machine could do this. Twenty years earlier, an airplane would’ve seemed like science fiction to most people. But 20 years after the flight at Kitty Hawk, airplanes were accepted by the public. The automobile hit the adjacent possible about the time Henry Ford introduced the Model T. The Internet got there thanks to Netscape’s Web browser, which teed up the late 1990s dot-com boom. Today, genomics and AI are in that zone.

Which brings us back to crypto. Bitcoin has been around for 10 years, and now there are more variations of cryptocurrencies than brands of cereal in a grocery store. Yet almost all crypto sits outside the adjacent possible. As much as you’ve heard about bitcoin, only about 5 percent of the American public owns any. And at this point, bitcoin is about the least-weird crypto offering.

Take, for instance, the Fan-Controlled Football League, or FCFL, in which fans can buy Ethereum-based FAN Tokens, which they put in a FAN Wallet and use to vote on which plays their team should run (or even the team name). A huge cross-section of American society loves football, so the FCFL seems like it could help introduce crypto to a larger audience. Instead, the FCFL sounds as confounding as a backyard time machine. The eight-team league starts playing its real games this year, testing the boundaries of the adjacent possible.

In 2018, CryptoKitties seemed to edge crypto closer to the adjacent possible. Also based on Ethereum, the app gives users a way to buy, breed, and sell virtual cats. Initially, the app got a boatload of press attention, and users created 1.5 million cats. But the popularity hit a dead end. Data from DappRadar shows that the number of users has nosedived to 200 to 400 a day.

Entrepreneurs keep trying to come up with crypto products and services that crack the adjacent possible. Coinlancer is offering crypto-based contracts that help freelancers find, track, and get paid for projects. Steemit is a social media site that uses the cryptocurrency Steem to pay users for posting valuable content. Never heard of either and don’t quite get how they work? That’s a sign that they still hover outside the adjacent possible. So is the fact that Steemit laid off 70 percent of its workforce last fall.

Still, the more that entrepreneurs and companies hammer at the technology, the more likely we’ll soon see a Wright brothers or Netscape Navigator moment — a point when some crypto invention cracks the adjacent possible and takes off. And when cryptocurrency gets there, it will no doubt give birth to a wave of new companies that will have an enormous impact.