From the Outside In

Faced with volatility, more companies are looking beyond their own ranks to find new leadership. Multimedia: Take the quiz “Are You a Likely CEO?”

In September 2015, Ralph Lauren, founder and chief executive officer of the fashion empire that bears his name, made news by announcing he would step down from his post as CEO. His decision to hand off the reins of his company wasn’t surprising — Lauren was about to turn 76, and the company’s financial performance had been slipping. Rather, the announcement was noteworthy because Lauren is known for favoring continuity in his clothing design and in management. During his nearly 50 years at the company, he had made it a practice to promote from within. And yet Lauren’s handpicked successor would be a newcomer to the firm, Swedish retail executive Stefan Larsson. Larsson had not lived and breathed Polo. And his prior experience was at discount-oriented retailing brands. But he was nonetheless a rising star in the business of fashion. Larsson’s accomplishments include driving successful international expansion over a 15-year career at H&M, and engineering an impressive turnaround of Gap’s Old Navy division, of which he was named president in 2012.

This episode is indicative of a broader trend evident in the high-stakes arena of CEO succession. Hiring an executive from outside a company to serve as chief executive officer has historically been a last resort — a move companies typically made only when a board of directors needed to force out the incumbent CEO suddenly, or had failed to groom a suitable successor, or both. Sometimes companies would interview outsiders as they were planning to make a change. But often those interviews were simply pro forma, and the board would revert to an insider as the final choice. That’s changing. Over the last several years, we have seen more companies deliberately choosing an outsider CEO. And when they do, more often than not, it is part of a planned succession.

As part of the 2015 edition of the annual Strategy& CEO Success study, we looked back at 12 years of detailed data on incoming CEOs at the world 2,500 largest public companies. In the latest four-year period (2012–15), boards chose outsiders in 22 percent of planned turnovers, up from 14 percent in 2004–07. That represents a 50 percent increase in the rate of outsider selection. And 74 percent of all the incoming outsider CEOs in 2012–15 were brought in during planned turnovers, up sharply from 43 percent in 2004–07 (see Exhibit 1).

Why are a higher proportion of newly chosen CEOs at large companies coming from outside? Several major structural factors are encouraging boards to widen their search for a more diverse set of competencies and backgrounds. Businesses in a wide range of industries are facing significant discontinuities — including industry convergence, digitization, and regulatory change. That appears to be leading boards to look harder for CEOs whose backgrounds, perspectives, and skill sets are different from those the in-house candidates possess. Boards of directors are also growing more independent, meaning there are fewer company insiders on them than ever before. These independent board members have a broader network of experiences, and have exposure to a broader network of executives. Meanwhile, investors of all types — but especially large institutional investors and activists — are bringing greater scrutiny to board decision making. Aggressive activist investors often explicitly state that bringing in a new CEO is part of their agenda.

For our part, we view the increasing attention given to outsider CEOs as a new step in the continuing evolution of CEO succession planning. As we demonstrated in last year’s study, the most important reason for succession planning is to ensure orderly transitions of business leadership. If this delicate maneuver isn’t carried off successfully, companies can lose momentum and see their financial performance decline significantly (see “The $112 Billion CEO Succession Problem,” by Ken Favaro, Per-Ola Karlsson, and Gary L. Neilson, s+b, May 4, 2015). This year’s study shows that succession planning at large companies continues to improve. The rate of planned CEO turnovers — as opposed to those in which CEOs were forced out — remained near its relatively high levels of the last few years. At the same time, the total number of turnovers rose in 2015, driven primarily by an unusually high rate of merger and acquisition–related turnovers, as well as by an uptick in forced turnovers (see “CEO Turnover in 2015”).

CEO Turnover in 2015

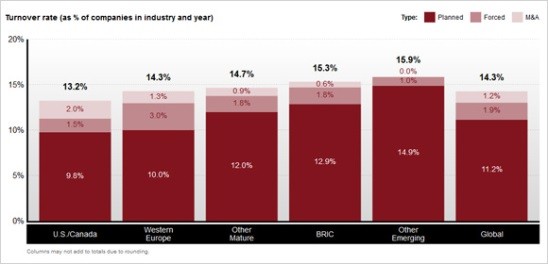

CEO turnover at the 2,500 largest companies in the world rose from 14.3 percent in 2014 to 16.6 percent in 2015 — a record high for the CEO Success study. The higher rate was driven by a combination of unusually strong M&A activity and a rise in the rate of forced turnovers. The overall rate of planned turnovers decreased slightly, but remained near the record high levels of the last five years (see Exhibit A).

In 2015, M&A-related turnovers accounted for 17 percent of all turnovers, the highest share since 2007. That’s not surprising, given the record US$5 trillion global deal volume in 2015. Of the turnovers not related to M&A, 22 percent were forced. That’s up from the low of 14 percent in 2014 and back to levels seen in 2012 and 2013.

Planned turnovers in 2015 were 78 percent of the total not related to M&A — near the 81 percent average over the last five years. From 2000 through 2010, the proportion of planned successions was only 65 percent. We believe the stable and high rate of planned turnovers — despite the surge of activity in M&A and forced turnovers this year — confirms that companies have made significant improvements in succession planning and practice.

Brazil, Russia, and India had the highest percentage of total turnovers in 2015, at 24 percent, close to the all-time high for these countries set in 2012. Japan had the next-highest rate, at 19 percent — up sharply from 12 percent in 2014. Nearly all those turnovers were planned. The lowest rate of total turnovers was in North America: Only 14 percent of U.S. and Canadian companies changed their CEO in 2015.

The telecommunication services business had the highest percentage of turnovers in 2015, at 25 percent, followed by energy (23 percent, up from 18 percent in 2014) and materials (20 percent). These three industries, together with consumer discretionary, consumer staples, and financial services, all reached five-year-high turnover rates. Information technology had the lowest turnover rate, at 11 percent, and was followed by healthcare (12 percent).

Despite the increasingly global nature of business, companies continued to favor hiring CEOs from the country and region in which the company was headquartered. Only 17 percent of incoming CEOs in 2015 hailed from a different country. This close-to-home trend was particularly visible in Japan (where only 3 percent of new CEOs came from another country) and China (6 percent). Western European countries were most likely to hire a foreign CEO, with 19 percent coming from a different country within Europe and an additional 11 percent coming from a different region. Globally, 72 percent of incoming CEOs had never worked in another region.

To be sure, the large majority of companies have continued to promote insiders to the CEO position. We think this will remain the preferred and predominant outcome, even though outsiders have now become legitimate choices rather than last-resort options. Boards of directors and senior leaders following well-designed succession practices should have a deep bench of internal candidates. They will know the candidates well, and will have played an important role in their career development. In many cases, insiders will continue to be the strongest candidates. But the discontinuities and other factors driving the outsider CEO trend suggest that boards and senior leaders may want to factor the outsider option into their succession planning.

In this year’s study, we look at the circumstances in which outsider CEOs are being hired and examine the characteristics of the companies that are hiring them. We also consider the attributes that boards should look for when considering outsider candidates, and how boards and senior leaders can bring them into the fold to give them the best chance of succeeding.

The Outsider Trend

Discontinuous change is the principal reason that more companies are turning to outsiders. Some industries, such as energy, are reeling from large and unusual swings in supply, demand, and prices. Others, such as telecommunication services, are moving from an asset-intensive to a consumer-intensive business model. Industries such as utilities and banking are adapting to major changes in regulatory policies. And in nearly all sectors, companies are rethinking their business models in reaction to the rise of digitization.

Companies that find the context in which they operate changing so rapidly often need leaders with experiences and skill sets that are different from the ones that can be found within the company’s current management ranks. Internal CEO candidates may have excellent records executing past — and even present — business models. But these candidates may lack the skills needed to lead companies through the transformations that will be necessary to succeed in the future, and the boards know it. Boards may also recognize that insider candidates are too steeped in the company’s past practices to envision new approaches.

Boards may also recognize that insider candidates are too steeped in the company’s past practices to envision new approaches.

Our data supports this explanation. The industries that have been most affected by discontinuities are those that have brought in a higher-than-average share of outsiders over the last several years. In telecommunication services, for example, outsiders made up 38 percent of incoming CEOs from 2012 to 2015, compared with the 24 percent average for all companies. Utilities had the next-highest share from 2012 to 2015 (32 percent), followed by healthcare (29 percent), energy (28 percent), and consumer staples and financial services (both 26 percent). The share of incoming insiders was below average from 2012 to 2015 in industrials (21 percent), consumer discretionary and materials (both 19 percent), and information technology (15 percent). The share of incoming outsiders at information technology companies, in fact, was much lower than in 2004–07, perhaps because the industry has been maturing and leadership development practices are now providing more internal candidates.

Institutional changes in the governance and leadership of companies, as well as in capital markets, are also making it more likely for companies to choose an outsider. Boards of directors have become much more independent in recent years, due both to regulatory changes made in the wake of the many post-2000 corporate governance scandals and to an overall drive for better corporate governance. In 2015, according to the Spencer Stuart Board Index, 84 percent of all board directors of S&P 500 companies were independent, and 29 percent of boards had a truly independent chair, up from 9 percent in 2005. The idea of separating the board of directors from company management has taken hold around the world, and the days of the 20th-century “imperial CEO” presiding over a board made up of insider directors are fading. The share of incoming CEOs also named board chair has fallen precipitously over the last 12 years, and hit a record low of 7 percent in 2015.

This sea change in board independence has brought greater diversity to the way boards evaluate CEO candidates. Company insiders are often unable to imagine that anyone from outside the company could understand or manage the business better than insider managers, particularly when the board chair was once the CEO. Outside directors, by contrast, look at the universe of potential future CEOs through a wider aperture. (There is one area in which diversity seems to be in retreat, however: gender. See “2015: Not the Year of the Woman CEO”.)

Another reason boards have become more independent — and, we would argue, more professional — is shareholders’ demand that they do so. Institutional shareholders have become more willing to use their power and their voices to push for changes in governance, strategy, and leadership. Since the 1990s, large public employee pension funds have become more active, and more recently, hedge funds have become a force for shareholder activism. In 2015, according to Activist Insight, 551 companies around the world were subjected to public demands by activists, up 16 percent from 2014. Almost half the companies at which an activist investor gains a board seat replace their CEO within 18 months, according to SharkWatch, the corporate activism database of FactSet Research Systems.

Our data shows that the background of the incumbent CEO also affects the likelihood of choosing an outsider. We found that the longer the tenure of an outgoing CEO was, the less likely it was that the successor would be an outsider. When the outgoing CEO had been in office for four years or less, an outsider was selected as successor 28 percent of the time. When the outgoing CEO’s tenure was between four and eight years, the outsider share fell to 21 percent. When the outgoing CEO had been in office for eight or more years, the share of outsiders chosen as successor fell to 17 percent.

Whether the board chair was formerly the company CEO also affects the likelihood of an outsider appointment. Over the last six years, companies at which the board chair was not the former CEO hired outsiders 28 percent of the time, compared with 16 percent at companies where the board chair was the former CEO.

The choice of an outsider CEO also seems to be somewhat self-reinforcing. We found that companies whose outgoing CEO was an outsider were more than twice as likely to choose an outsider as the new CEO. From 2004 to 2015, only 18 percent of companies with an outgoing insider chose an outsider in planned and forced successions; this compared with 36 percent of companies with an outgoing outsider.

A final reason for the growing prominence of outsiders in CEO turnovers is that the nature of employment has changed dramatically over the last several decades. New employees joining a large company as late as the 1970s — especially those pursuing executive careers — had good reason to believe their career at the company might continue until retirement. Few people who have entered the workforce since then have been under any such illusion. And given that the median age of incoming CEOs in 2015 was 53, most CEOs assuming office recently and in the future will be more comfortable with the idea of moving to another company.

Financial Performance

Historically, there has been a strong correlation between poor financial performance and the subsequent hiring of outside CEOs. Companies have been one-third more likely over the last 12 years to select an outsider CEO in both forced and planned successions when the company has been underperforming financially, as measured by total shareholder return (TSR) over the tenure of the outgoing CEO. From 2004 to 2015, 25 percent of outsider CEOs who were appointed in planned successions replaced CEOs who had generated TSRs in the bottom quartile, compared with 16 percent of the incoming insiders. In the last two years, however, boards in all regions have become more likely to appoint an outsider in a planned succession even when the outgoing CEO has performed well. In 2015, for example, high-performing companies (those in the top performance quartile) hired a larger share of outsiders than did low-performing companies. The reason, we believe, is that better-performing companies tend to have better succession planning, and they are better able to judge when an outsider is the right choice.

Insider CEOs have historically outperformed outsiders over their tenure — due in part to the fact that most outsiders were hired in a forced succession. Because the companies had not been performing well, these outsiders started with a performance disadvantage. Since we began tracking succession data in 2000, departing insider CEOs have delivered higher median shareholder returns over their entire tenure in all but a few of the years we tracked — often by a meaningful margin. In the last three years, however, the insider performance premium has disappeared (see Exhibit 2). One reason, we believe, is that the recent crop of outgoing CEOs includes a higher number who were hired in planned rather than forced turnovers, and fewer of them were themselves forced out.

Geographic Range

There are significant regional variations in the way that companies with different performance characteristics hire outsiders.

North America. Over the last 12 years, poorly performing companies in the United States and Canada were just as likely to hire an outsider CEO in forced turnovers as in planned ones. High-performing North American companies in planned successions tended not to choose outsiders. Their superior performance suggests that choice may be because they also have good leadership development and succession planning. North American companies were also less likely to hire serial outsiders than were other companies, particularly Western European companies. Again, we believe this shows that superior succession planning enables these companies to choose outsiders for strategic purposes — to change direction, for instance — and these firms are then able to follow the outsiders with internal candidates who can continue the new direction. In forced successions, high-performing North American companies hire a large proportion of outsiders. The reason is that forced departures among these companies are the result of boardroom struggles (as well as, in some cases, ethical lapses) rather than performance problems.

Western Europe. In comparison with North American companies, Western European companies in general are hiring outsiders more reactively than proactively, and have evolved less in improving leadership development and succession practices. Between 2012 and 2015, companies in Western Europe hired far more outsider CEOs (30 percent) than did companies in the U.S. and Canada (18 percent, combined). Moreover, the outsider hiring rates in Europe were clearly higher than in North America for both low- and high-performing companies in forced and planned turnovers. What’s particularly interesting is that low-performing European companies were much more likely to hire an outsider CEO in forced turnovers — 51 percent of the time, compared with only 34 percent for North American companies (see Exhibit 3). In addition, outsiders at European companies underperformed from 2012 to 2015 — a third were in the lowest TSR quartile, compared with 20 percent in North America — and they were more than twice as likely to be forced out.

Emerging markets. Companies in countries such as Brazil, Russia, India, and other emerging markets are hiring a much larger percentage of outsider CEOs than companies in Western Europe and North America. In Brazil, Russia, and India, for example, 38 percent of incoming chief executives in the 2012–15 period were outsiders, up from 25 percent in the preceding four years. We believe emerging markets companies are hiring more outsiders partly because of a lack of talent in these fast-growing markets and partly because these regions’ governance practices and leadership development programs are less effective than those in North America and Western Europe.

Looking Outside

When should a board of directors consider choosing an outsider CEO rather than promoting from within? Once they have made the determination to go outside, how should they identify and evaluate the best candidate? And how can they create the right conditions to enable the new CEO to succeed?

One circumstance in which an outsider makes sense, as we’ve described above, is when the company must surmount a disruptive challenge or threat to its established business model. When this happens, internal candidates may not have the skills to lead the company in its next incarnation. But outsider candidates may have already demonstrated, in past jobs, the new skills the board is seeking. Boards may also determine that the company needs to make a discontinuous, step-change improvement in its performance, which will require wholesale changes in its former strategic and operating plans. Because they don’t have biases and commitments built up over the years, outsiders can make changes more objectively. They also may be able to look at the organization from a broader perspective that is based on an understanding of what the world will require in the future.

The board may find it difficult to judge whether an internal candidate has the right capabilities to meet future needs when the company is facing discontinuity. Past performance is measurable, and thus easier to judge, but it may not be a good predictor of success in a new context. Boards may therefore feel more comfortable with outsiders in these situations. But outsiders should also be legitimate candidates in cases where discontinuous change is not an issue. Even in companies with robust CEO succession programs in place, internal candidates sometimes are simply not ready to lead the company. This typically happens when a company has let too many promising executives leave the company for greener pastures, or when the board has planned poorly or delegated the responsibility for choosing a successor to the incumbent chief executive.

Once a determination has been made to consider an outsider candidate, the board should begin by identifying the key desired characteristics. A candidate must have expertise in the areas where the company faces future challenges. In some cases, the board may be specifically looking for a background in the company’s industry. Among financial-services companies, for example, risk management and regulatory requirements are highly specific to the industry and require deep knowledge of products and business practices. For that reason, 92 percent of the industry’s incoming outsider CEOs from 2012 to 2015 came from other financial-services companies. But in other industries — where technological discontinuity or industry convergence is an issue — experience in a different industry may be more important. In the utilities industry, where unbundling and regulatory liberalization are changing the competitive context, 72 percent of incoming outsiders from 2012 to 2015 came from other industries (see Exhibit 4).

In addition, many boards will want a candidate with prior experience as a CEO, and will have a strong view of the kind of management style they deem necessary for the company and its future success. Boards may also want to test potential future CEOs by recruiting them first to senior positions on the leadership team (such as chief operating officer or chief financial officer) or as members of the board of directors. This affords an opportunity for the potential candidate to get exposure to the company and its culture, and for the board to get to know the candidate.

Easing the Transition

The board’s work is not over once it has made a selection. It must also carefully consider the way the outsider CEO is introduced to the public, to the management team, and to the rank and file. When an outsider is brought in to deal with discontinuous change, the new leader needs time — early on — to develop his or her perspective on the industry, to establish the company’s position in the marketplace, and to determine how he or she plans to change the game. The board needs to be closely involved in providing support, offering an unvarnished view of the company’s position, and defining expectations clearly. The board members should also set a standard for how they want to be involved in agenda setting and execution, particularly if the company is experiencing performance difficulties, or if ethical problems have drawn public scrutiny. The chairman should invest extra time in listening to and guiding the new CEO, sharing his or her reflections on the company, the industry, and the path forward.

The new outsider CEO must try to operate confidently in uncharted terrain that is studded with pitfalls and land mines. He or she must balance the pressure for quick results with the imperative to make fundamental changes — while creating the space needed to learn on the job. From our experience working with chief executives in many sectors and industries, we have identified four critical practices for outsider CEOs.

1. Do only what only a CEO can do. The CEO needs to focus rigorously on issues that are unique to the position: shaping the company’s definition of success; breaking the frame (for example, by changing some fundamental aspect of the company’s business model); resetting expectations; and integrating the company’s parts with the whole. Decisions made and actions taken in previous years might have made sense at the time, but a new marketplace requires different ways of doing business. To break down human inertia, the outsider CEO should make clear that the company needs to be forward looking, and declare “amnesty” for any past mistakes.

2. Find the right pace for change. Only the CEO can set the pace for change within the company, and it may require pushing back against expectations of what can be achieved in the first 100 days. The outsider CEO will benefit from moving coherently and with deliberate haste. However, trying to accelerate too quickly — for example, in order to cut costs immediately — risks the prospect of the CEO not only addressing the wrong issues, but also missing opportunities to learn where the real problems lie. Managing pace is a way of managing expectations, which is essential for building sustainability and preparing the organization for the major changes that will be needed to meet its ultimate goals. Outsider CEOs have an advantage in creating a “new day” by resetting expectations and redefining roles with senior executives or with new executives if needed.

3. Get the culture working with you. Culture can be the primary impediment to an incoming outsider’s ability to lead transformational change. The CEO needs to address business priorities and change in ways the organization can reasonably accommodate. Understanding how the company’s culture influences both formal and informal behaviors is therefore essential. Outsider CEOs can become more like insiders by skillfully working with the informal elements of the organization.

4. Continually engage the board as a strategic partner. Given the pressure being placed on today’s boards, and the level of accountability expected from them, board members need to take part in the strategic conversation as it develops. The CEO’s responsibility is to lead the board to be bolder than it otherwise might be in challenging the company’s leadership and direction. Boards today also provide complementary skills by design, with specific members offering guidance in their areas of expertise, such as finance, compensation, operations, or markets. The CEO’s relationship with the board can leverage that expertise.

CEO transitions remain a difficult and perilous task. But our years of conducting this study have made us optimistic. We have seen that corporate governance in general, and succession practice in particular, have been improving. The increased willingness, desire, and capacity to consider outsider CEOs is a new element that may further improve the sophistication of succession planning. Although most companies will continue to promote from within, in line with their long-term succession plans, the stigma associated with hiring outsiders is dissipating. As globalization continues, the pool for available talent has never been deeper or more densely populated. To their credit, more boards are casting wider nets.

Reprint No. 16210

Methodology

The CEO Success study identified the world’s 2,500 largest public companies, defined by their market capitalization (from Bloomberg) on January 1, 2015. We then identified the companies among them that had experienced a chief executive succession event between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2015, and cross-checked data using a wide variety of printed and electronic sources in many languages. We also used Bloomberg to compile a list of companies that had been acquired or merged in 2015.

Each company that appeared to have changed its CEO was investigated for confirmation that a change occurred in 2015. Additional details — such as title, tenure, chairmanship, nationality, and professional experience — were sought on both the outgoing and incoming chief executives (as well as any interim chief executives). Company-provided information was acceptable for most data elements except the reason for the succession. Outside press reports and other independent sources were used to confirm the reason for an executive’s departure.

Finally, consultants from Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business, separately validated each succession event as part of the effort to learn the reason for specific CEO changes in their region. To distinguish between mature and emerging economies, Strategy& followed the United Nations Development Programme 2015 ranking. Total shareholder return (TSR) data over a CEO’s tenure was sourced from Bloomberg and included reinvestment of dividends (if any). TSR data was then regionally market adjusted (measured as the difference between the company’s return and the return of the main regional index over the same time period) and annualized.

Author profiles:

- DeAnne Aguirre is an advisor to executives on organization topics for Strategy&, PWC’s strategy consulting business. She is a San Diego–based principal with PwC US.

- Per-Ola Karlsson leads Strategy&’s organization and leadership practice in the Middle East. He is a partner with PwC Middle East.

- Gary L. Neilson is a thought leader on organization design and leadership for Strategy&. Based in Chicago, he is a principal with PwC US.

- Also contributing to this article were s+b contributing editor Rob Norton and Spencer Herbst, a Strategy&researcher and senior associate with PwC US.