Epics of Enterprise

A connoisseur of corporate histories conducts a guided tour of the favorites in his collection.

(originally published by Booz & Company) |

|

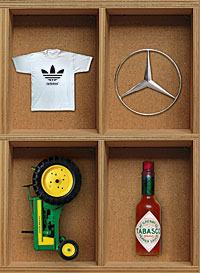

Photograph by Opto

|

In 1986, British writer Robert Lacey, author of biographies of Sir Walter Raleigh, Henry VIII, Princess Diana, and Grace Kelly, published what was perhaps his most ambitious work: Ford: The Men and the Machine, a history of the family-controlled Ford Motor Company. In the final pages, Lacey describes how, in the fall of 1984, he sat in the office of Henry Ford II (CEO since 1960 and grandson of the founder) and watched him methodically feed documents into a paper shredder. Lacey noted that these documents had “to do with history, the letters and reports and memoranda which [made] up the record of his years in the company.” Pressed by Lacey to explain why he was so intent on destroying history, Ford responded, “What I’ve done in my life is nobody’s business.”

That view was consistent with the sentiment once expressed by his grandfather: “History is bunk!” It also underlines the problems that writers of corporate history encounter. Business leaders are notoriously uninterested in reflecting on the past. Neither are they likely to be tolerant of a “warts and all” biography of their company. And this tunnel vision is reflected in the curricula of graduate business schools, most of which do not offer courses on the history of business.

Nonetheless, the great stories of business success, failure, influence, and drama manage to survive. Even the Ford Motor Company preserved thousands of documents: a cornucopia of letters, contracts, photographs, and business records covering every aspect of the company’s history, including the controversial operation of its German subsidiary during World War II. This constitutes probably the most extensive archive in the business world, and it is lodged in the Henry Ford Museum near the company’s Dearborn, Mich., headquarters. Interest in Ford has sparked 94 books, including Douglas Brinkley’s Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress, 1903–2003 (Viking, 2003), described by Rob Norton in this magazine as a “company history that’s a pleasure to read, consistently insightful, and informative on several levels.” (See “Have You Read about Ford Lately?” s+b, Winter 2003.)

In the end, every company has a story to tell, often a profound one — and even when the leaders are vehemently opposed to it, those stories have a way of getting out. When they do, these broad-based tales of enterprise, judgment, and mishap can be compelling and enlightening for anyone to read. And they can provide inspiration for people seeking to navigate difficult times, as so many of us are today.

As a journalist, I have been writing about business for 55 years, and I bring to the subject a passionate interest in history. When I enter my office at home, I face a wall of shelves that hold about 250 corporate biographies. Most of them, of course, are not very high-quality works. Corporate histories are generally hagiographies, funded and brought to fruition by the companies themselves, often commissioned by the PR department to flatter the leaders of the moment. They depend for accuracy on the permission of the company being profiled, and on access to its files and people. They typically have little impact on business practice. And they often go unread; I have rarely heard of a corporate history that makes the bestseller list.

A few great corporate histories, however, have transcended the limitations of the genre. They are fascinating, rewarding epics. These stories can instill pride in employees, and they tell the rest of us a great deal about a company’s strategy, its successes and failures, and the usually intertwined fates of the founders’ families. They can also illuminate the times — the social, political, and economic milieu that a company both is shaped by and helps shape. Most of all, I cherish the human stories they tell.

A Seven-generation Saga

One of the gems in my collection is The Thistle and the Jade: A Celebration of 150 Years of Jardine, Matheson & Company, a sumptuous story of one of the great trading companies of Hong Kong. (The thistle represents Scotland, where most of the partners of the firm came from, and the jade, China.) Originally published in 1982 to mark Jardine’s 150th anniversary, this book shows that a history sponsored by the company being profiled need not be a dud.

With 272 nine-by-12-inch pages, The Thistle and the Jade appears at first to be just an outsized coffee-table book. But it is also a work of unusual thoughtfulness. It sketches the Far Eastern saga of the trading house through the eyes of 10 observers who explore different aspects of the company’s history. The last chapter was written by the late John K. Fairbank, the Harvard professor who created the field of modern Chinese studies in the United States.

The result is a stunning history and a delight to the eye, replete with more than 240 illustrations that serve as a treasure trove of artifacts and memorabilia. The chapters themselves are not dry academic treatises but well-written narratives of a merchant bank whose operations were played out against a background of the Opium Wars, two world wars, and the rise of Chinese industry under a Communist regime. Along the way, the firm expanded to include Hongkong Land, the largest commercial property holder in Hong Kong; Dairy Farm, a retailing complex that operates 3,800 stores in Asia, including supermarkets, beauty shops, convenience stores, and restaurants; the Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group; and Astra International, the largest automotive company in Indonesia.

Members of the founding families played active roles in the firm up to the present day, and in the production of the book as well. Editor Maggie Keswick was a descendant of cofounder William Jardine; she died in 1995. The current edition — a 2008 update to mark the firm’s 175th anniversary — was edited by Clara Weatherall, wife of Percy Weatherall, a seventh-generation scion of the Jardine family who worked for the bank in the Philippines and Hong Kong.

Fairbank, in his essay, notes that the “aggressive acts with which the British and others humiliated the Chinese in their own country were very obvious at the time and have been remembered ever since,” but he deplores simplistic theories assigning all blame to foreign forces. And he credits Jardine Matheson for being a “catalyst, sponsor, initiator, or challenger in China’s push toward modernization.”

Germany’s Auto-innovators

Many people believe that the automobile was invented in the United States. Not so. The Star and the Laurel: The Centennial History of Daimler, Mercedes, and Benz, 1886–1986, another great corporate his-tory, recounts the tale of Daimler-Benz AG (now Daimler AG), maker of the Mercedes-Benz line of automobiles. The book was first published in 1986 by Mercedes-Benz of North America, championed by public relations director Leo Levine. Although its list price was US$80, most copies were distributed gratis to customers, dealers, the press, and others, including more than 15,000 libraries across the country, as “our birthday present,” Levine said.

Like The Thistle and the Jade, this is a large-format, lavishly illustrated book. It runs 368 pages and is written by veteran automotive writer Beverly Rae Kimes. The story begins in 19th-century Germany, where two engineers, Carl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler, tinkered for years with internal combustion engines in workshops 60 miles apart, neither aware of what the other was doing. They each put their models on the road in 1886, 22 years before Henry Ford launched his Model T. Kimes describes in detail the ups and downs these two pioneers experienced before getting their motorized vehicles to work.

The Star and the Laurel — the name refers to the Mercedes-Benz logo — is a must-read for any automobile enthusiast. Here you see photographs of early models, pictures from the races that established both the Benz and Daimler cars, old advertisements and posters, postage stamps featuring the cars, and photos of famous race-car drivers like Barney Oldfield and Alfred Neubauer, as well as the royal personages and millionaires who were the early buyers. Harris Lewine, a celebrated art director and book designer, was responsible for the graphics.

In the 1890s, most of Daimler’s sales came from motorboats. But American piano maker William Steinway promoted the cars in his catalogs: “Daimler motor vehicles do away with [the] heavy expense and unpleasantness connected with horses, such as stable smells, harness and feed bills, [and] clouds of dust from horse hoofs [that] smother you while out riding.” In 1893, when Chicago held its World’s Columbian Exposition, Daimler had the automotive section all to itself — and Gottlieb Daimler, accompanied by his new bride, attended the fair. Another interested visitor was Henry Ford. Carl Benz, meanwhile, was selling cars all over the world. By 1899, with 2,000 cars produced, he ranked as the world’s largest automaker. The merger of Daimler’s company and Benz’s took effect in 1926 (26 years after Daimler’s death), uniting the two companies that had ushered in the automotive age.

One of the prime movers in the early years of Daimler was Emil Jellinek, the son of a Bohemian rabbi, who sold cars to wealthy people on the French Riviera. He produced so many orders that the company acquiesced to his demand that the cars carry the brand Mercedes, the name of his daughter. It’s not clear whether Adolf Hitler knew that his favorite car had been named for a Jewish girl.

Some readers might be tempted to dismiss The Star and the Laurel because of its omissions. For example, it contains almost nothing about the Nazi era. (Other histories, like Neil Gregor’s Daimler-Benz in the Third Reich [Yale University Press, 1998], have documented the company’s role as an arms manufacturer, and its harsh treatment of the Jewish men and women forced to work in its plants.) And of course, this book was published 12 years before the company’s disastrous acquisition of Chrysler.

Nonetheless, The Star and the Laurel stands as a rich chronicle of a company that started with two garage tinkerers (the Hewlett and Packard of their era), ushered in the automotive age, set a standard for performance and luxury, and survived while 5,000 other automotive companies fell by the wayside.

The Culture of Deere

John Deere’s Company: A History of Deere & Company and Its Times also falls into the blockbuster category. An 880-page tome with 275 illustrations, it celebrates rural Americana and the growth of the iconic farm equipment manufacturer founded by blacksmith John Deere in 1837 when he invented the self-cleaning steel plow. It’s an absorbing story, well told by the late Wayne G. Broehl Jr. (a professor for 33 years at Dartmouth College’s Amos Tuck School of Business Administration), who spent six years researching and writing it. Deere funded the project, imposing only one caveat: no release of information about products under development.

John Deere’s Company should serve as a model for any company contemplating a history. Despite its ponderous size, it’s not dull, in part because of the wonderful illustrations, but also because Broehl always places the company’s history in the context of world events. For example, the flood of immigrants to the United States during the first decade of the 20th century is reflected in the following statistics on the 2,500-strong workforce at Deere’s main plant in Moline, Ill.: Swedes and Norwegians, 36 percent; Belgians, 18.6 percent; Russians and Jews, 10.5 percent; Germans, 4.1 percent. During the Great Depression, Deere made special efforts to take care of farmers (suspending their installment payments) and laid-off employees (continuing their health insurance). The author also describes business lines that didn’t work out. Did you know that Deere twice made an effort to enter the bicycle market?

The book, which was published in 1984, ends with the accession of Robert Hanson to CEO in 1982. In the previous 145 years, the company had had only five CEOs, all of them direct descendants of John Deere or husbands of descendants. Hanson, although not a member of the Deere family, explicitly carried on the family’s strong ethical sensibility, and that in turn affected the next great book about the company, The John Deere Way: Performance That Endures by David Magee.

Twenty years after John Deere’s Company was published, Magee — a prolific Tennessee-based journalist who has written books on General Electric, Ford, Nissan, and Toyota — started to search for what he called “America’s most values-based business.” He has said that it didn’t take him long to narrow the list to one: Deere & Company. He wasn’t fazed when he learned about Wayne Broehl’s massive account — indeed, he lavishes it with praise — because he wasn’t interested in writing a conventional history of Deere. And The John Deere Way was not sponsored or funded by Deere & Company.

Magee set out to draw a cultural portrait that would offset all the bad news about business, and he pulls it off in 234 pages. He weaves history into his account, making it one of the most trenchant books dealing with corporate social responsibility that I have seen. He succeeds because he shows the link between Deere’s business — making tractors, combines, lawn mowers, harvesters, and log skidders — and its strong, 170-year-plus commitment to integrity. I loved his comments about the importance of Deere’s brand, its insistence on making products that look good and work well, and its decision in 1956 to seek out Finnish-born architect Eero Saarinen to design a sleek, seven-story, glass and unfinished steel headquarters sometimes referred to as the “Versailles of the cornfields.”

Heat from Louisiana

Family is the theme that runs through many corporate histories, especially those dealing with privately owned companies where the founding families are still at the helm. In McIlhenny’s Gold: How a Louisiana Family Built the Tabasco Empire, Jeffrey Rothfeder (a senior editor of this magazine) traces the spicy tale of Tabasco sauce. The McIlhenny company is still owned and controlled by the family that founded it in 1868.

Rothfeder had a tough job, because the McIlhenny family members still active in the company refused to help him. He went around them — interviewing current and former employees and other McIlhenny family members and researching virtually everything that has ever been written about the company. And, in the end, he produced a lively, informative history, one that should interest anyone who has ever dropped a smidgen of Tabasco sauce into a Bloody Mary.

The book is illustrated with black-and-white photographs. You won’t want to miss the shot of McIlhenny employees stuffing those tiny bottles of Tabasco into a cardboard shipping container (they don’t seem to be having a good time). And it has a fascinating tale to tell: in Rothfeder’s words, “unbelievable…at least…when the truth is told.” He discounts official stories told by McIlhenny as fanciful inventions.

McIlhenny has always guarded its history closely. It began on Avery Island, which sits on a salt mountain surrounded by the bayous of the Louisiana coast 140 miles west of New Orleans. (The Dave Robicheaux mystery novels by James Lee Burke are set nearby.) Even the origin of Tabasco sauce is cloaked in mystery. Rothfeder accepts the fact that the sauce, a combination of Tabasco peppers, vinegar, and salt, was concocted by Edmund McIlhenny after he returned from the Civil War and started the company, but he documents that a similar sauce, also called Tabasco, was made and distributed 20 years earlier in New Orleans, where Edmund McIlhenny had been a banker long before going off to fight for the Confederates.

In any case, Edmund was the first to squeeze the peppery sauce into those miniature bottles, and by the early 1880s he was selling more than 20,000 bottles a year at the wholesale price of a dollar a bottle ($15 in today’s money). Today, the factory on Avery Island turns out 600,000 bottles every 24 hours — and it’s a tourist attraction.

Rothfeder glories in describing McIlhenny’s ultimately successful campaign to get the rights to use the Tabasco name as a registered trademark. First, in 1870, Edmund patented a recipe for making the sauce — and, according to Roth-feder, he purposely lied in his application about the ingredients, listing bisulfate of lime, ostensibly to retard fermentation. Rothfeder says McIlhenny added that ingredient to “sabotage anyone who attempted to use the patent as a crib sheet to copy the product.” How devious can you get?

Plenty. In a patent claim in 1906, John McIlhenny, son of the founder, stipulated that his was the only company in the U.S. making a pepper sauce called Tabasco. That was untrue; there were at least a dozen others, including H.J. Heinz Company and Campbell Soup Company. In 1909, the patent office rescinded the Tabasco trademark after learning about this deception. Despite this ruling, the company continued to warn distributors and retailers that it was illegal to sell any sauce labeled Tabasco that did not come from McIlhenny. Then, in 1918, the U.S. Court of Appeals in New Orleans, in a stunning setback to competitors, said that McIlhenny had a “common-law” right to use the name, asserting against the known facts that Edmund was “the first person to grow those peppers in the United States.” Whatever political engineering went into that decision, it certainly represented a great victory for the McIlhennys: akin, as Rothfeder puts it, to getting the trademark rights for Wisconsin cheese or Idaho potatoes.

Another chapter in the McIlhenny saga involves the company town that was built on Avery Island. E.A. McIlhenny, younger brother of John, took the reins of the company in 1906 and immediately began building bungalow homes for the company’s workers in what was dubbed Tango Village. More than 500 people would eventually live in these homes. To compensate for low wages, rent was free. There was a distinct caste system, described by Rothfeder as follows: “The Anglo-Saxon McIlhennys were, of course, the bosses. The few non-McIlhenny supervisors…were generally of mixed origin, part Cajun and part French, Spanish, or Anglo. Most of these trusted employees were given homes on the island a little roomier than those of the common worker…. One step below the non-McIlhenny managers were the factory hands, who were nearly all Cajun and consigned to less luxurious quarters…. The pepper pickers, who were black, belonged to the bottom caste. None of them was allowed to reside on Avery Island. In fact, the only people of African or Caribbean descent with homes on the island were McIlhenny servants.” In its typical secretive manner, the company kept quiet about this replica of pre–Civil War plantation society.

With the exception of 24 months in the late 1990s, every CEO of the company has been a McIlhenny. The current chief executive is Paul McIlhenny, great-grandson of the founder. About 200 McIlhenny family members make up the sole shareholders. Rothfeder believes the company has reached a turning point, needing to decide whether to continue as an independent entity, to sell shares to the public, or to become part of a bigger company like Kraft or Campbell Soup. The company supposedly has standing $1 billion-plus offers, but Rothfeder points out that “no one yet has gotten wealthy betting against the McIlhennys.”

Spirits from Cuba

Another celebrated family-owned company is Bacardi & Company, the producers of Bacardi rum. Journalist Tom Gjelten, like Jeff Rothfeder, set out to tell the story of an idiosyncratic family empire. Unlike Rothfeder, however, Gjelten had the complete cooperation of the family members. He has produced a solid, engaging book that is as much a history of Cuba as it is of the company. A sip of your next daiquiri will summon up the stories in Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba: The Biography of a Cause. And you will love the vintage photos of white-suited Bacardi family members and employees (they have a regal, tropical look).

Gjelten traces the history from 1862 — when Don Facundo Bacardi, an immigrant from Catalonia, figured out a way to make the first light rum and started a distillery in the eastern Cuba city of Santiago — to 2008. The company, which is headquartered in Bermuda but run, in effect, from Miami, ranks as the world’s third-largest alcoholic beverage company. It makes not just rum but Dewar’s whiskey, Martini & Rossi vermouths, Bombay gin, and Grey Goose vodka. And it is still owned by the same family that started it.

Fidel Castro’s takeover of Cuba in January 1959 was a life-changing event for Bacardi. And Gjelten has painstakingly demonstrated why this was not a simple case of a rapacious company being upended by a Socialist-minded government. The politics of the Bacardis, going back to the founder, were liberal and nationalistic. They treated their workers well and opposed Spanish colonial rule. Don Facundo’s son, Emilio, was a writer and activist who became mayor of Santiago and a senator in the Cuban legislature. He was imprisoned twice for aiding rebels seeking the overthrow of the Spanish regime. And the family had no use for Fulgencio Batista, who seized power in a 1952 coup and established a harsh and corrupt military dictatorship.

When Fidel Castro first appeared on the scene, the Bacardi family welcomed him. Pepin Bosch, who was married to the founder’s granddaughter and was then chairman of Bacardi, told reporters: “The triumph of the revolution makes me very happy.” Three weeks after the fall of Batista, there was a wedding rich in symbolism: Castro’s brother, Raul, was married to Vilma Espin, the daughter of a longtime Bacardi executive, Jose Espin. The winter 1959 issue of Bacardi Grafico, the company’s quarterly magazine, celebrated Castro’s victory with an article called “Crusade of Freedom.”

But less than a year later, it was all over. Castro moved to nationalize 300 companies; one of them was Bacardi. On October 15, 1960, Daniel Bacardi, great-grandson of the founder, met in his office with representatives of the government. With him was the treasurer of Bacardi and three executives who had married granddaughters of Emilio Bacardi — and they turned the company over to the state, including every physical asset Bacardi owned in the country.

Most of the Bacardi family members fled to the United States, where they regrouped. In fact, from a business standpoint, the exile may have been a blessing in disguise. Fortunately for rum drinkers, the company already had distilleries in Puerto Rico and Mexico. In 1961, a new distillery came on line in Brazil, and the company announced that it would build a $4 million distillery and bottling plant in the Bahamas, enabling Bacardi to export rum tax-free to all the British Commonwealth countries. Later on, distilleries were opened in Canada, Martinique, Panama, and Spain. In 1960, when its Cuban company was nationalized, Bacardi had sold 1.7 million 12-bottle cases of rum worldwide; by 1976 annual global sales had jumped to more than 10 million cases.

Now, with the acquisition of other brands, Bacardi has become a major player in the global wine and spirits business. But the Cuban connection still hangs over the company. As Gjetlin puts it, “Rum is one of the precious elements — along with cigars — that keep a hallowed place in Cuba no matter which ideology rules.” What will happen if the Castro regime ends? Will the Bacardi family ever want to return to Cuba? Gjetlin doesn’t try to answer those questions. But he deserves high praise for presenting a dramatic and sensitive portrait of a company placed against a canvas of political upheaval. That’s what a good corporate history is all about.

How the Shoe Fits

For one of the best insights into the making of a corporate history, see Donald R. Katz’s preface in his 1994 profile of Nike Inc., Just Do It: The Nike Spirit in the Corporate World. Katz relates that when he first approached Nike founder Phil Knight with his book idea, Knight said no, explaining, “Our competitors already just follow our lead. Why should we let everyone else know how we do it?”

That was in the summer of 1993, when Katz had already completed an article on Nike for Sports Illustrated. Two weeks before the article was published, Knight called and said he had changed his mind. He did not yet know how the Sports Illustrated piece would treat his company, but he allowed Katz to head for Asia with open access to Nike’s people and factories. Katz spent months inside Nike, and his book catches the hyperkinetic atmosphere of the company. Katz says Knight knew the book would have some negatives about Nike, but that was acceptable to him. He recognized that “an honest portrait of a company in motion must include such errors and setbacks.”

Did competitors glean valuable intelligence from Just Do It? Very unlikely. Nike continued its dominance of the athletic shoe business, which apparently provoked the 2005 merger of its competitors Reebok and Adidas. Barbara Smit’s book, Sneaker Wars: The Enemy Brothers Who Founded Adidas and Puma and the Family Feud That Forever Changed the Business of Sport, published in 2008, describes how Paul Fireman, CEO of Reebok, felt about his main competitor: “Nike always thinks of whoever is their number one opponent as a warlike enemy. They’re insane, sick, disgusting.” (What a poor loser he was.) Readers of Smit’s book might well apply those epithets to the two companies at the center of her inquiry, Adidas and Puma, established by two brothers who hated each other so much that they started rival companies in the small Bavarian town where they were born.

I end this essay with these two books about the athletic shoe business because they demonstrate the strength and weakness of the corporate history form. Such histories provide a view of business life that no other form can provide — certainly more sweeping and compelling than the average case study — but they are as poor at helping companies become more successful as books about wars are at helping prevent future ones. Nevertheless, I want to put in a good word for the corporate history. If nothing else, learning about the roots of a company’s culture is fascinating. Who wouldn’t want to know that many of the early cookie brands baked by Nabisco were named after towns near Boston: Brighton, Beacon Hill, Melrose, Shrewsbury, (fig) Newton? (See Out of the Cracker Barrel: The Nabisco Story, From Animal Crackers to Zuzus, by William Cahn [Simon & Schuster, 1969].) Or that Procter & Gamble was the first company to establish a profit-sharing plan, in 1887? (See It Floats: The Story of Procter & Gamble, by Alfred Lief [Rinehart, 1958].) Or that Alfred Krupp, great-grandson of the founder of the German industrial giant bearing his name, lived in a 300-room castle on the Ruhr River and purposely had his study placed over the stables so that he could smell the horse manure, which he found enriching? (See The Arms of Krupp, by William Manchester [Little Brown, 1968].)

Maybe corporate histories don’t help business leaders learn from others’ mistakes. But at their best, they remind us that corporations are human enterprises, with human roots, which make them diverse and even powerful in ways that will never be captured by a balance sheet alone. And if a company needs to change direction or renew itself (as so many do, these days), perhaps the most compelling way for its leaders to start is by reminding themselves of the epic nature of a great company’s life trajectory — from the gleam in a founder’s eye to an enterprise that employs thousands and changes the world, and then sometimes to a kind of rebirth.![]()

Reprint No. 09210

Author profile:

- Milton Moskowitz is a member of the editorial board of Business and Society Review and codeveloper (with Robert Levering) of Fortune magazine’s annual survey of the “100 Best Companies to Work For.” He is the author of seven books, including Everybody’s Business: A Field Guide to the 400 Leading Companies in America (Doubleday, 1990).