Eastern Germany’s coal belt emerges from the shadows

How a region that based its economy on fossil fuels is becoming a renewables hub that benefits its people and attracts new businesses.

Where massive bucket wheel excavators once tore through the countryside in central-eastern Germany, uprooting entire forests and towns, today a sea of over half a million shiny solar panels and 460-foot-tall wind turbines—enough to power 100,000 households—stretches to the horizon. In the shadows of the massive smokestacks that used to belch black fumes into the sky, a hydrogen research lab and Europe’s largest renewable-energy storage facility are pushing the frontier of decarbonization technology.

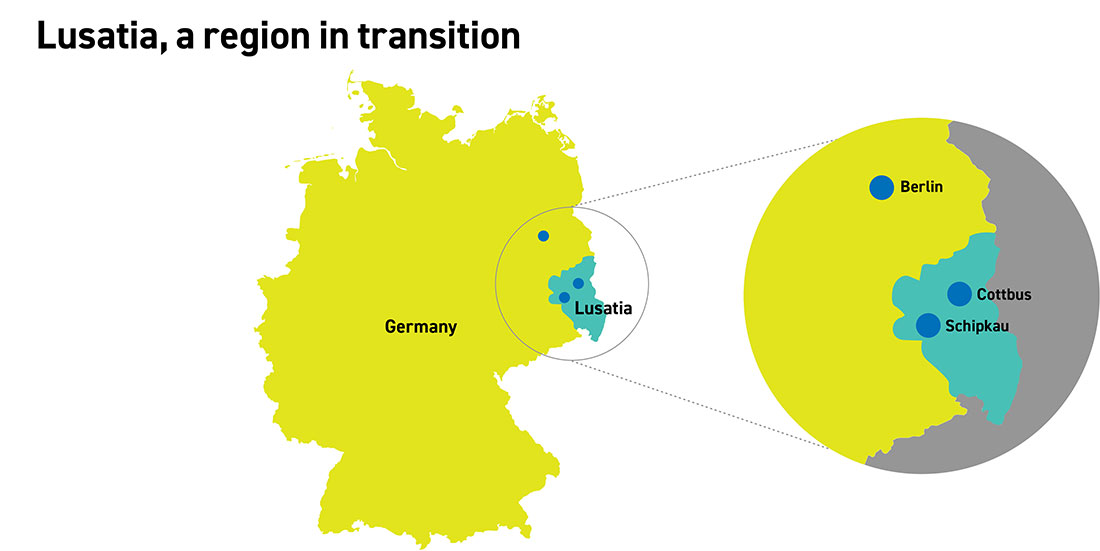

This isn’t the Ruhr valley, the industrial heartland of Germany’s prosperous West. This is Lusatia, a region roughly twice the size of Delaware that straddles the German–Polish border. Thirty years after reunification, the region and its 1 million residents—bypassed by much of the prosperity of the postwar years—are burying their past as one of the nation’s main lignite producers and building a sustainable economy led by renewable energy and clean-tech companies.

It hasn’t happened overnight—Germany started its long transition to renewables at the end of the 20th century, and it’s far from over—and there have been missteps along the way. But the reinvention of the region provides significant lessons for both governments and businesses on how transformation is possible when there is a collective effort that marries incentives, government policies, and business needs with climate goals.

Areas that depend on mining coal and burning it for electricity face a particular challenge in a post-COP world. Power generated by the dirty fossil fuel is the single biggest contributor to human-created climate change. And if targets set by the 2015 Paris Agreement are to be met, CO2 emissions will need to be cut by 45% by 2030, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). What’s more, last November, world leaders at the Glasgow climate summit agreed, for the first time, to “phase down” coal power.

Under Chancellor Angela Merkel, Germany had pledged to stop burning coal for electricity by the year 2038. The administration of her successor, Olaf Scholz, is aiming to bring that target forward by eight years. Getting there won’t be easy, but in recent years, renewable energy has grown to account for nearly half of Germany’s generating capacity. The energy transition, helped by the falling price of solar panels, has gained a particular impetus in Europe, where the cost to pollute the air has risen sharply. Europe’s benchmark carbon price tripled in 2021, to €89 (US$101) as of early December, and is still above €85 ($97).

But coal still accounts for just over 30% of Germany’s electricity generation. And there are 20,000 coal-related jobs in Lusatia alone, so the journey is far from over. The history of Lusatia’s transition, even with its many false starts, shows that a new model can replace the high-value but dirty extraction industry. Government-encouraged investments in renewables to replace coal mines have attracted companies—like BASF and the Canadian firm Rock Tech Lithium—seeking low-emissions power. And as Germany’s mobility industry gears up to shift to the post–combustion engine era, parts and components makers have joined in, including battery manufacturer Altech Industries Germany GmbH, which is looking to invest in the region. “We’re harvesting energy from land that nobody really wants, and we don’t have to transport it very far,” says André Steinau, head of the hydrogen unit of GP Joule, the company that is building, and in part owns, a 300-megawatt solar farm in Schipkau, a town of 7,400 situated two hours south of Berlin.

A long journey

This was a region that found it difficult to catch a break. After World War II, Lusatia became part of communist East Germany and was dominated by coal production. In the decade after reunification in 1989, unprofitable coal mines and coal-fired power plants were closed. A lack of planning, financing, and local participation meant there was little to fill the void and less to drive an economic revival. The result was widespread discontent, soaring unemployment, and a rural exodus that created more than one ghost town in the region. The jobless rate peaked in 2005, at more than 18%, and it has taken 15 years to fall in line with the national average.

The history of Lusatia’s transition, even with its many false starts, shows that a new model can replace the high-value but dirty fossil fuel–extraction industry.

Indeed, the early days of winding down coal were marked by trial and error. Take what happened to the former open-pit mine Spreetal-Nordost, some 23 miles south of the regional capital, Cottbus. In 1997, private entrepreneurs announced plans to build a Wild West theme park, complete with bison, bears, and Billy the Kid–themed attractions. That project fell through two years later for a lack of investors, as did an idea to create a golf resort.

Efforts to spark tourism and take advantage of the many lakes formed by flooding decommissioned open-pit mines produced mixed results. Some restaurants and hotels have managed to gain a foothold in a nascent hospitality industry, but in the face of a shifting economic landscape and poor infrastructure, others are struggling.

Mario Stenske, 56, who had hoped to manage the Wild West park and golf resort, teamed up with partners to buy land and run a farm about 20 miles south of Cottbus, in Elsterheide. But due to the poor soil, yields from Stenske’s crop are roughly a third of his neighbors’. So, an idea was hatched to run a horse ranch on the side. It took 10 years to get the infrastructure in place and finally obtain the necessary construction permits. That same year, 2010, Stenske’s hopes and plans were literally buried when the former mining land around him collapsed, one of many landslides in the region that have destroyed houses, equipment, and livestock.

The nearby lake that was to attract tourists for water sports was supposed to have been filled by 2010, but water rationing and high acidity levels have kept authorities from giving the green light for lake-based tourism at the site, a delay that’s likely to continue for another year or two. After resettling to more solid ground, Stenske eventually built a bed and breakfast, which opened in 2020, a month before COVID struck. Since then, it’s been touch and go.

Still, Stenske remains optimistic. For the short time that the Terra Nova B&B has been open for business, it has showed signs of potential. With its themed rooms, cozy cafe, and views of the surrounding pine and birch forest, the B&B has attracted local families seeking a weekend getaway and cyclists stopping for coffee and cake. Nearby, Galloway cattle graze and free-range chickens roam. Terra Nova is a mini-oasis in a previously battered landscape. “We’re tied to this land,” says Stenske. “There’s no going back now. I just hope the coal exit strategy means we get more predictability than we’ve had in the past.”

Spreewerk Lübben, an explosives disposal company, is another example of the challenges involved in repurposing a business in Lusatia. A munitions maker during the communist era and now an affiliate of San Diego–based General Atomics, the company had focused for years on defusing surplus Cold War ammunition stockpiles. More recently, it decided to transition to the e-mobility business by recycling batteries. The biggest hurdle, says managing director Ramon Kroh, wasn’t a lack of capital, technology, or skilled workers but good old bureaucracy. “A greenfield project would have been easier than using our existing plant,” Kroh says, referring to the difficulty the company had getting licenses to operate.

But the business environment seems to be changing, and not only for Kroh, who is optimistic he’ll soon obtain his licenses. Since the country agreed on a comprehensive coal exit plan in 2020, there is more government support and coordination and a clearer idea of where the region wants to go. Most important, there is widespread acceptance that the coal industry really is coming to an end. “The objective is to avoid the traumatic experience of the early 1990s,” says Heiko Jahn, head of the regional development agency Wirtschaftsregion Lausitz GmbH, which is charged with fostering businesses, infrastructure, and competitiveness. “There was much fighting to keep the mines alive because people couldn’t imagine any alternative, but now they’ve made peace with it. We’re all moving in the same direction.”

Renewable power

Renewables are leading the way in Lusatia, both for generating power and for attracting businesses. Indeed, using renewable energy locally helps to sell the idea to outside businesses and investors and makes economic sense. Part of the energy generated by the solar farm in Schipkau will be converted into green hydrogen that will fuel local buses—under new European regulations, transportation companies must gradually improve the carbon footprint of their fleet. A hydrogen filling station is scheduled to be completed by the middle of 2022, according to Klaus Prietzel, Schipkau’s mayor.

In 2019, Tesla chose Brandenburg, the German state that includes much of Lusatia, for its EV and battery production site. BASF is also building battery materials and recycling plants at its facility in Schwarzheide. “Investors knocking on our doors wouldn’t have discovered our state on a map two years ago,” said Jörg Steinbach, Brandenburg’s economy minister. During a visit to Germany in May 2021, President Biden’s environment envoy, John Kerry, touted the state’s capacity in renewables, and Steinbach echoes that praise: “The companies that come today demand clean energy, and preferably a light carbon footprint from suppliers as well. That is our main attraction; that’s what brings foreign investors.”

In 2021, Rock Tech Lithium picked the town of Guben, around 25 miles northeast of Cottbus, over other European sites for a new lithium converter plant, in part because of financial incentives. The factory, which will cost nearly half a billion euros, will supply 500,000 electric cars with batteries each year. It will be powered by locally sourced renewables. Recycled batteries are to make up 50% of the plant’s raw production materials by 2030.

The transformation of the regional energy giant LEAG is another Lusatia success story. Blasted by environmentalists for burning tens of millions of tons of lignite each year, the power utility is restructuring to embrace clean energy before the coal phase-out is complete. To that end, LEAG is building one of Germany’s largest solar farms (400 megawatts) on the site of a former mine near Cottbus. The utility also intends to deploy solar panels on a nearby lake that was once a lignite pit. In 2020, it inaugurated Big Battery Lusatia, Europe’s largest energy storage facility, boasting a utilization capacity of 53 megawatt hours. With its ability to produce and store electricity, LEAG can offer a more consistent and predictable power supply, which is more attractive to users.

“It’s our goal to be one of the big green power generators by 2030,” says Andreas Huck, LEAG’s head of new business and digitization. “We still have a lot to catch up because we started from scratch only five years ago.”

Selling more than an idea

While attracting big corporate names is important, economy minister Steinbach says there is also the need for a “bottom-up” process in which local businesses, communities, and entrepreneurs take ownership of their own projects. In fact, the involvement of locals, many of whom worked in the mining industry and were skeptical of new industries, is essential to any transition, says Prietzel, Schipkau’s mayor. Eight years ago, the town introduced an annual citizens’ bonus paid every Christmas from the sale of wind energy—Schipkau was an early adopter and is now home to 55 turbines—that amounted to €50 ($57) per inhabitant. And before contracting the solar farm—which covers an area bigger than New York’s Central Park—Prietzel held numerous town hall meetings and obtained unanimous approval for the proposal in a December 2020 vote. “Transparency is the key to everything,” he says. “When you explain, show, and communicate to people, they’re more likely to understand and support you.”

What’s happening in Lusatia can serve as a model for other regions scarred by decades of mining. Repurposing fossil fuel sites as Lusatia has done can have the flywheel effect of attracting investment, especially in areas with thousands of acres of post-mining land. From central Australia and the Ukraine to India’s Jharkhand state, abandoned or soon-to-be-closed mines are plentiful. Australia is home to approximately 80,000 inactive mines, and utilities are anticipating decommissioning coal-fired power plants. Utility-scale batteries are planned at several sites, including the Hazelwood coal mine in Victoria. And a clean energy hub and green hydrogen plant are under study in Hunter Valley, New South Wales. In the US, a defunct coal mine in Kentucky is being turned into a 200-megawatt solar farm. “All you need is land, sun, and consumers, and you can make this happen anywhere in the world,” says GP Joule’s Steinau.

Meanwhile, back in Schipkau, Mayor Prietzel is mapping out new projects, building on the success the town has had with its solar and wind farms. His plans? To build a green energy–fueled data center that will employ 1,000 people. He’s already signed a memorandum of understanding with investors, and construction is to begin in 2022. Prietzel, who himself hails from a miner’s family, also wants to bring the nation’s tallest wind turbine to town, once it’s fully licensed. “It’s so high, it practically doesn’t stop—just imagine.”

Author profile:

- Raymond Colitt is a journalist with three decades of experience reporting, writing, and editing stories from around the globe, including Brazil, Germany, and the US. He has worked for the Financial Times, Reuters, and Bloomberg and currently divides his time among Berlin, Los Angeles, and Brasilia.