Giving CFOs more power in the marketing ecosystem

Can chief financial officers help companies make the most of their investments in digital advertising?

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of strategy+business.

The advertising ecosystem is changing rapidly. Back in the Mad Men era, marketing departments could trace only tenuous relationships between campaigns and sales. Today, an abundance of data and powerful technological tools afford marketers the ability to discern direct attribution links and quantifiable return on investment. An executive can track just how many direct sales of a wrap dress a Twitter ad campaign produced, how many of those buyers were new customers, and how the spending affected the margin on each product sold. In theory, marketers can prove in great detail, to the satisfaction of the most exacting financial minds in their organization, precisely how they contribute to the top line.

In theory.

In practice, the structure and opacity of the digital advertising ecosystem make it much more challenging to get an actual read of where all the money goes. There’s an old line among ad pros that we know half of all advertising is wasted; we just don’t know which half. In the digital realm, there’s a newer, more troubling statistic: Only about 25 cents of every dollar spent on digital ads results in the placement of an ad that is seen by a real human. Although marketers are working hard to get a handle on how their campaigns produce value, they could use an assist from colleagues who have a different set of capabilities: chief financial officers.

Among other things, CFOs see it as part of their role to diligently evaluate the audit trail for most company costs. And whether the spending is on energy, office leases, or capital, CFOs often just need to task colleagues to aggregate and analyze budgets, and monitor the cash coming in and going out. But advertising spending is often a blind spot, particularly in the digital realm. That may seem strange, given the size and importance of the industry: According to Ad Age, U.S. advertisers will spend close to US$500 billion on marketing and media in 2021. And according to the PwC Global Entertainment & Media Outlook, global spending on digital ads in 2020 was $125 billion, and it is growing at a healthy annual rate of 4.2 percent. But authoritative data on marketing spending mostly exists at an aggregate level. And without granular, itemized receipts, finance teams are unable to determine where a company may be spending unnecessarily.

Given the importance and size of this category of spending, CFOs cannot afford to continue viewing marketing expenditures as a black box. Rather, they must prioritize understanding the advertising ecosystem, and then apply the line of rigorous financial questioning they bring to other areas of the organization.

With that goal in mind, how can CFOs wade into the world of media optimization and effect financial change?

CFOs historically have not needed to know much about the ins and outs of marketing. And that puts them at a disadvantage when they get together with their colleagues on the marketing side. They can start getting up to speed by becoming better acquainted with the marketing ecosystem.

Fragmented marketplace

CFOs should begin by understanding the two main reasons that marketing spending is so difficult to track. First, it’s very fragmented. A chief marketing officer doesn’t just pick up the phone and place orders for ads with a single entity. Large companies often work with multiple agencies; one may specialize in social media, another in TV. And each agency is allocated only a portion of all marketing dollars. Because money is spent in these silos, companies lack a holistic view. And even in instances in which all marketing functions are performed in-house, spending is often scattered across different brands, regions, and platforms. These divisions leave the CFO without a single source of truth as to how the marketing spend is being allocated.

Second, nearly three decades after the dawn of digital advertising, the details of how and where advertising dollars are spent are still extremely murky. The best example of this phenomenon is in programmatic media, which, according to media agency Zenith, will account for 72 percent of all digital media globally in 2021. Programmatic media is the use of automated technology to purchase ad space. Advertisers buy ads via a real-time auction that occurs within milliseconds, similar to trading a stock electronically. This system allows for advertisers to quickly buy ads from a variety of publishers, ensuring that ads are targeted to the right audience, in the right context, and at the right time. For instance, every time a web page loads, buy- and sell-side platforms are having a rapid-fire conversation, selecting the optimal ad to serve that particular user.

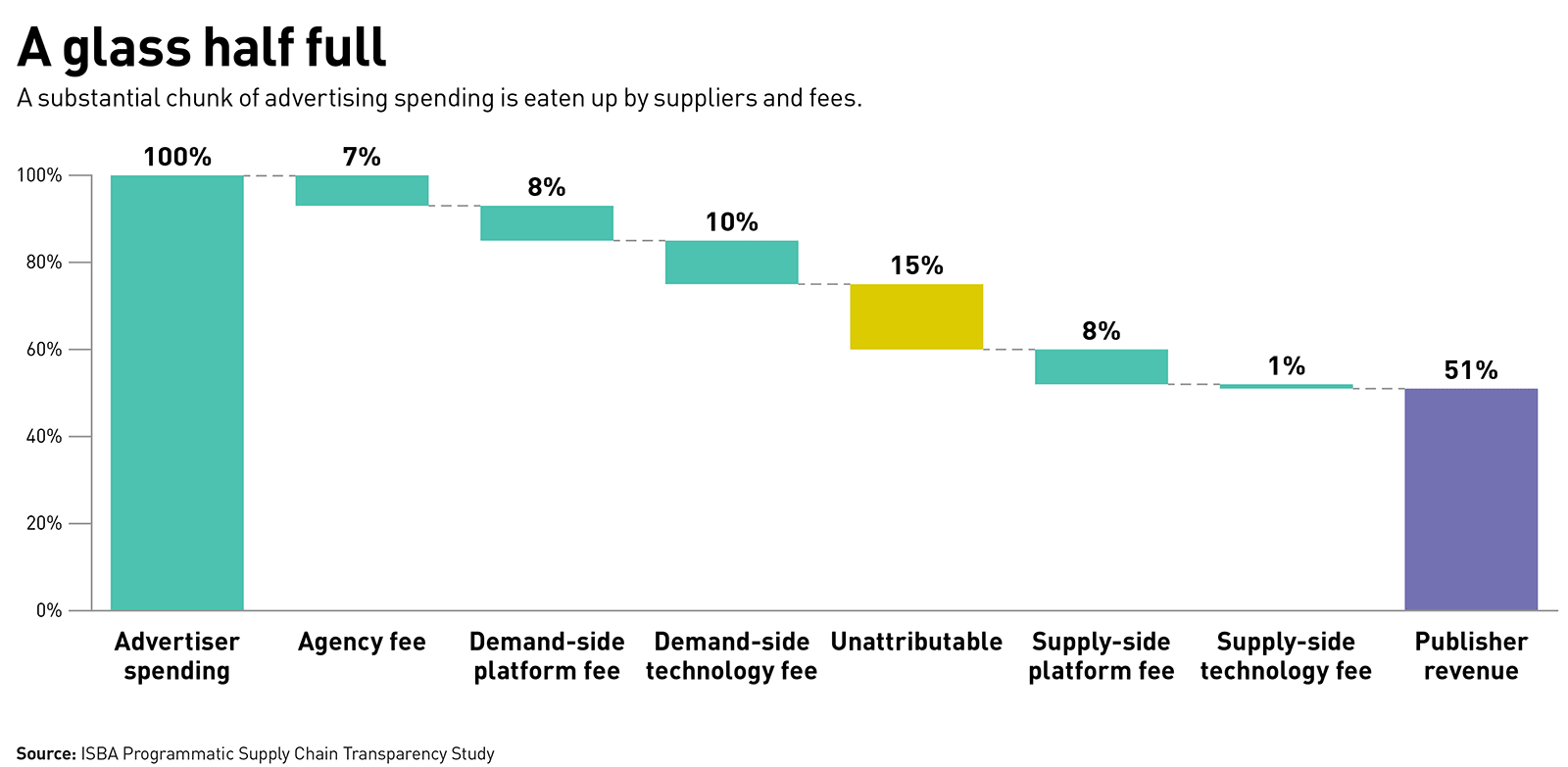

This marketplace dynamic enables greater speed and better targeting, but it also masks enormous inefficiencies in the supply chain. That’s because there is an immense amount of leakage along the way. A recent study PwC conducted with ISBA showed just how much: Only half of an advertiser’s spend reaches the publisher (see chart). The other half can be difficult to track. Intermediaries account for a significant amount, though advertisers know neither which player is responsible for which portion of that spend nor how expensive each player is in the context of the greater market. The study also found that about one-third of the supply chain costs — about 15 percent of total spending — is completely unattributable, simply lost to the system. Additionally, advertisers are likely losing more value than the study suggests, as the data stops at the publisher and does not quantify impressions that may not be seen by an actual human. For instance, advertisers pay when a bot “views” one of their ads, or when an ad is loaded onto a page but located below the fold and remains unseen by a user. Including this type of waste, it’s not inconceivable that only about a quarter of total spending can be tracked through to actual human impressions.

Marketing budgets are thus subject to many types of value leakage. Low visibility leads to an inability to redirect funds away from partners that deliver poor value for the money. Without understanding how strategies are performing, marketers can’t allocate funds with precision. Without granular data, they cannot distinguish which inventory may be delivering suboptimal returns. And because these are industry-wide issues, there is no way to benchmark against peers and glean competitive dynamics.

Asking questions

Here’s where CFOs come in. Because supply chain value leakage is a problem that permeates the advertising ecosystem, many marketers either are not aware of this problem, do not know to what extent this problem affects their budget, or simply accept this problem as a necessary evil. CFOs with an understanding of the space are therefore positioned to challenge their marketing departments and agencies with difficult questions that, when answered, could ultimately result in great value for the company. Those questions may include:

- How much of our media spending is on the purchase of ad space compared with the production of ads?

- How much of our media budget is wasted on ads not viewed by a consumer?

- How much are the fees charged by each individual player in the digital media supply chain?

- Which of our partners are providing poor value for the money?

Of course, to a degree, CFOs are approaching the marketing world as outsiders. And, like every other discipline, marketing has its own rules, culture, and norms. To contribute in a constructive fashion, CFOs should strive to gain a general understanding of various platforms and methods of media buying by reading marketing outlets such as Adweek and Ad Age; attending marketing conferences that cater to finance such as the ANA (Association of National Advertisers) Media Conference; and even taking a marketing course — perhaps on programmatic media like the one the Trade Desk offers. This will empower CFOs to work with their marketing departments as collaborators, as both move toward a solution that brings transparency to the supply chain and aim for a spending allocation that prioritizes high return on investment.

It’s not inconceivable that only about a quarter of total ad spending can be tracked through to actual human impressions.

Once they’ve joined the conversation, CFOs can contribute by tapping into one of their other strengths: monitoring. The CFO is uniquely positioned to set new reporting standards, hold teams responsible for financial goals, and demand transparency into advertising spending — as well as to ensure such monitoring is an ongoing process. When both marketing and finance are aware of the questions listed above, companies can begin to craft plans to address knowledge gaps. CFOs can reevaluate how to optimize marketing budgets. Additionally, marketers may be able to adjust in-flight campaigns in order to test different outcomes or drive better results. Incorporating financial media campaign tracking technology can ensure transparency and compliance in media spending, and unlock significant value. If CFOs do not have full transparency, they should be looking to incorporate these tools into their technology stack.

The rise of digital continues to blur traditional organizational divisions, underscoring the need for finance and marketing leaders to come together in order to drive true transformation. Given marketing’s role as a growth driver of the business, it is vital for all members of the C-suite to gain alignment on how to address the issues created by the transformational changes of digital advertising.

Author profiles:

- Derek Baker is a leading practitioner with PwC’s CMO advisory group and focuses on helping companies navigate the intersection of data, technology, and media strategy. Based in San Francisco, he is a principal with PwC US.

- Ravi Patel the former head of product and CEO at AdFin, advises clients on digital marketing and media strategies for PwC. Based in New York, he is a director with PwC US.

- Alison Lisnow advises consumer market clients for PwC. Based in New York, she is a senior associate with PwC US.