Superhuman resources: How HR leaders have redefined their C-suite role

The trials of 2020 have thrust human resources into the spotlight. The HR leaders who have shined know how to help their companies thrive.

A version of this article appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of strategy+business.

For all the ambiguity caused by the historic events of 2020, one thing is certain: The center of gravity in leadership teams has swung toward the human resources function. Yes, other members of the C-suite, such as finance, marketing, and legal, also have important functional responsibilities that keep the company in full stride. But there’s one person who is being put on the spot to answer the many unexpected questions that companies are facing this year.

These questions are fundamental to the business. Some may be existential. How do companies keep everyone safe as they shift to remote working overnight? How do leaders provide medical, emotional, and mental health support at a distance? How do they gauge performance and develop talent so that people can thrive in this era of uncertainty? What is the company’s stance on social movements such as Black Lives Matter? How is it delivering real change when it comes to inclusion?

All eyes in the room (or on video calls) have turned to the chief human resources officer (CHRO) for the answers. “The financial crisis of 2008 relied on CFOs to help their companies,” said Tanuj Kapilashrami, group head of HR at Standard Chartered bank. “But the companies that will come out stronger from [2020] will be those that have a strong HR function.”

That represents a sea change. For decades, the HR function struggled to be heard in the C-suite, primarily because it was expected to manage only personnel transactions. That wasn’t enough for some CHROs, though. A handful started to redefine the possibilities of the role, including contributing to strategic decision-making. This reinvention also meant that individual CHROs — leaders of a new “superhuman resources” function — took on additional responsibilities, including commercial real estate, customer experience, and organizational transformation. The expansion of the role has led to growing stature within many organizations for one of the more gender-diverse roles in the C-suite. (Of the 44 senior CHROs we recently interviewed, 23 were women and 21 were men.)

The importance of CHROs varies widely from company to company. “Many CEOs say they want a strategic CHRO, but they often don’t think through what it really means,” said Jorge Figueredo, the former longtime head of HR at McKesson Corporation. However, this year has in many ways ended those Hamlet-like musings about what the function should be and should not be. CHROs are in the spotlight, which adds urgency to the question “What sets the great CHROs apart?”

At Merryck & Co., we have a strong vantage point from which to observe the transformation of the role. Since 2010, we have spent considerable time with well over 500 CHROs in the U.S., the U.K., and Australia, discussing their challenges and watching the development of new approaches to their work. And we have seen patterns in the way the most effective ones have developed their roles. Many of the interviews we conducted with CHROs were for our recent Strategic CHRO interview series on LinkedIn. In those conversations, we steered clear of company-specific questions and instead asked about the leaders’ frameworks for doing their job, what they’ve learned, and what CEOs have had to change in order to fully leverage HR.

The CHROs we’ve interviewed and worked with represent, according to their CEOs and boards, some of the highest-impact leaders in the field. We spoke with career HR leaders such as Donna Morris, CHRO of Walmart, and with others for whom the top job was their first role within HR, such as Kathleen Hogan at Microsoft. Collectively, they represent a broad and deep range of experiences, including working through CEO successions; navigating wholesale cultural and business model transformations; translating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) priorities into measurable outcomes; and serving on company boards themselves.

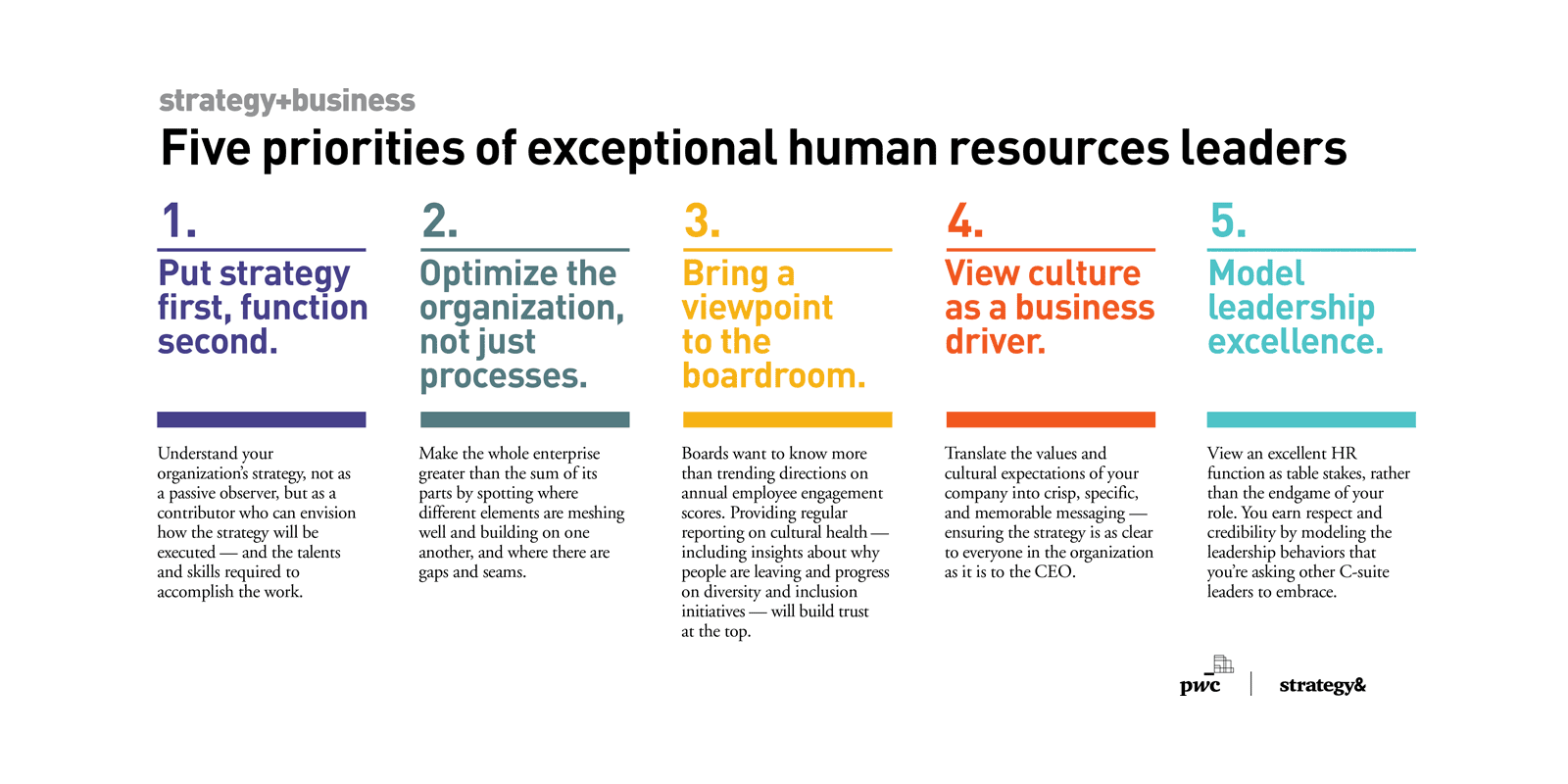

From those conversations, five priorities emerged for maximizing a CHRO’s contributions to the organization. Together, they establish new benchmarks for defining the role and measuring its performance. The complexity of the top HR job is intensifying, particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Simply defining exactly what CHROs do remains a challenge. “This role is fascinating because it’s a job almost without a job description,” said Rhonda Morris, the CHRO of Chevron. “We live in a world where virtually everything is gray, rather than black and white.”

To be clear, company-specific attributes will always be contextual and unique. But to help provide more clarity amid the ambiguity — and to provide a useful foundation for HR executives, CEOs, and board directors to build upon — here are the key priority themes that we have identified. We included extended quotes from many CHROs to help bring the themes to life.

Priority 1: Put strategy first, function second

World-class CHROs understand their organization’s strategy, not as passive observers but as contributors. They can see the implications of any new initiatives on revenue streams and contribute to discussions about the competitive landscape. Though HR is categorized as an “enabling” function, the best CHROs are active contributors within C-suite team discussions. Rather than being seen as the office of “no” with a primary focus on risk and compliance, they work to find ways to say “yes” to new initiatives. They bring a unique perspective and expertise for building and executing human capital agendas, and they embrace the label of commercial.

“I am a businessperson who happens to know a thing or two about HR,” said Kirsten Marriner, the CHRO at Clorox, a multinational manufacturer of consumer and professional products based in Oakland, Calif. “That’s how I approach it — how you equip yourself with knowledge, your skills, how you spend your time, how you frame questions, how you think about opportunities, how you think about what you’re here to do. It’s about being clear on the purpose of your HR organization in service of the broader business objectives. So, I wear an enterprise hat first, and I wear a functional hat second.”

Marriner added: “I often say that we’re not here to do good HR for the sake of good HR. It is about driving business outcomes with all the levers and tools that we have at our disposal. The point is to not put yourself in a box. In my first CHRO role, the CEO said early on to the whole executive team — there were eight of us who reported to him — that if somebody walked into our staff meeting and listened to us for a while, they should have no idea who does which jobs, because everybody is contributing to every discussion about the business.”

If somebody walked into our staff meeting and listened for a while, they should have no idea who does which jobs, because everybody is contributing to every discussion about the business.”

CHROs have to be able to envision how the strategy will be executed, the talents and skills required to accomplish the work, and the qualities needed from leaders to maximize the organization’s potential. Increasingly, that requires a nuanced understanding of how technology and humans will interact.

“HR leaders sit at a crossroads because of the rise of artificial intelligence and can really predict whether a company is going to elevate their humans or eliminate their humans,” said Ellyn Shook, the CHRO of professional-services firm Accenture. “We’re starting to see new roles and capabilities in our own organization, and we’re seeing a whole new way of doing what we call work planning. The real value that can be unlocked lies in human beings and intelligent technologies working together.”

Priority 2: Optimize the organization, not just processes

CHROs must operate at a slightly higher altitude than their peers on the leadership team to ensure that the different parts of the business work well together. At their best, these leaders view the entire organization as a dynamic 3D model, and can see where different parts are meshing well and building on other parts, and also where there are gaps and seams. The key is to make the whole organization greater than the sum of its parts.

“In the past, HR was about optimizing a process, like incentive plans or talent development plans,” said Susan Podlogar, CHRO of New York–based insurer MetLife. “Now HR is expected to provide macro solutions rather than micro solutions. It’s moving to optimizing the organization, not just a function or process, and moving to maximizing the productivity of the organization as an integrated whole.”

Podlogar cited work she was doing with MetLife’s chief technology officer to identify where tech advances could augment the company’s workforce. They were exploring how to best leverage technology so that a supervisor in the customer service group could monitor, on the basis of length of pauses, tone of voice, and the words customers were using, whether a call was proceeding well or whether someone needed to step in to help. The goal was not to replace the person handling the call, but to support that person’s work.

“Leaders in the past could operate in silos and achieve outcomes, but now optimal solutions come from networks,” Podlogar said. “The problems that businesses are facing are becoming so complex that organizations have to come together much quicker to facilitate a solution. That’s not how many business leaders have operated in the past, but that’s a specialty HR can drive. This is the new way of working.”

And it’s not just a matter of optimizing the strategy for today. The best CHROs also see industry disruptions as opportunities, rather than threats, and look for ways to align the workforce and the business to take advantage of those opportunities.

“As industries overlap more and more, innovation is not happening anymore in silos,” said Paul Baldassari, who led HR for Flex, a U.S.–Singaporean manufacturer of components, for five years. “The strategic challenges for companies are accelerating. Companies get disrupted really fast, but they also have huge growth opportunities if they can react quickly. That’s where the strategic element of the CHRO function comes into play. Innovation is happening between the operations function, the HR function, the engineering function, and the IT function. You need to be able, as a CHRO, to bridge those gaps and have a holistic view about combining all of that and making a new strategic service available in the company. It’s about changing your company’s strategy around talent so that you connect the dots going forward between all those different industries for the ‘people supply chain.’”

Given that framework, perhaps it’s no surprise that Baldassari was asked in 2019 to take over as executive vice president in charge of strategic programs and asset management at Flex. There are also many examples of CHROs who have been given new responsibilities as chief transformation officers, including Brian McNamee of biotech company Amgen and Dermot O’Brien of ADP, which develops human resources management software.

“There are a lot of intricate moving pieces when you cut across the range of things you do in HR — from pension plans in different countries to comp to diversity to leadership,” O’Brien said. “There are all these categories, and they all have to fit together. For me it was a good training ground, because any transformation is a cultural change.”

Priority 3: Bring a viewpoint to the boardroom

Culture has shifted from a “nice to have” conversation to a “need to have” discussion in corporate boardrooms. Many widely publicized corporate scandals can be traced back to gaps between the stated culture and the ways in which people actually operated. A truly healthy culture is a major draw for talent. But a poor culture, insufficiently explored or addressed at the executive and board levels, represents a significant reputational risk for how the company is perceived by consumers as well as prospective recruits and investors.

Boston-based investment firm State Street Global Advisors, for example, said it will be taking into consideration the cultural practices of companies as part of its investing strategy. “We all know the old chestnut that culture eats strategy for breakfast,” the firm wrote in an open letter to boards in 2019. “But studies show that intangibles such as corporate culture are driving a greater share of corporate value, precisely because the challenges of change and innovation are growing more acute.”

Culture issues are leading to harder conversations in the boardroom with directors who want to know more than trending directions on annual employee engagement scores. “When I joined my first board, the topic wasn’t regularly on the board agenda,” said Beth Comstock, former vice chair of Boston-based General Electric, who is currently on the board of Nike. She said a director’s role includes pushing for more detail. “When you ask to see culture surveys, don’t just settle for the aggregate results. Show us the worst ones. Show us the toughest feedback that caused you concern. Ideally, it becomes an ongoing discussion.”

And CHROs are responding with more detailed dashboards for measuring cultural health. “Boards should expect regular reporting and discussions on pulse surveys from employees, alumni surveys that give [them] insights about why people are leaving, and retention rates for high performers,” said Amy Cappellanti-Wolf, reflecting on her work at software services firm Symantec, where she’d led HR for more than five years. “On a quarterly basis, I report out to our board on our culture and our efforts related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. A board has to be asking for more of that information — not to armchair quarterback, but to have a good sense of what’s working and what’s not. Nobody wants to be surprised. I think some boards have been surprised when these ethical concerns or questions about a talent drain come up. You need to have facts and data for the conversation with the board.”

And those conversations become easier when CHROs build relationships with directors outside the regular board meetings. That way, the CHRO establishes his or her reputation as an independent protector of the company. “The head of HR should not only report to the CEO but should also have a core relationship with the board of directors,” said Donna Morris, of Walmart. “The HR function should be pretty independent, just like audit is on the board. If you really are going to act as an ombudsman for the effective operation of your organization, you have to feel like you can push back against your peers and even the CEO.”

Priority 4: View culture as a business driver

The best CHROs excel at translating the values and cultural expectations of the company into crisp, specific, and memorable messaging, and they understand the importance of relentless communication. The strategy has to be as clear to everyone in the organization as it is to the CEO. And these CHROs strive to create processes and a work environment that will help recruit and retain talent. At its best, culture is a virtuous circle, beginning with the articulated values that are reinforced and referenced in rewards and promotions, as well as the practices for hiring, firing, and onboarding.

“I’m crystal clear that the CEO has to own purpose and culture, but heads of HR have this unique vantage point and unique ability to help in that discussion,” said Kevin Cox, who was appointed CHRO at General Electric in 2019. “It’s another reason why it’s so important for the CHRO and CEO to connect. I believe that most CEOs don’t have that complete answer, and I don’t think most CHROs do either. My definition of culture is that it is what leaders do, not what they say. I spend a lot of time trying to pull culture into leadership behaviors at the top of the organization. In a company that is super-clear about its purpose and culture, the head of HR might want to shift focus from developing culture and purpose to thinking about how culture, strategy, and talent actually intersect. The most important Venn diagram to me is the one that shows those three aspects intersecting.”

One of the strongest case studies of culture driving strategy can be found at Microsoft, where Satya Nadella orchestrated a remarkable turnaround when he took over as CEO in early 2014. To help him lead that transformation, he reached out to Kathleen Hogan, who at the time was running Microsoft’s US$5 billion services organization, with about 20,000 employees. To many, the change from managing an important P&L to running HR may have seemed like a demotion. Nadella saw the role as key to delivering his strategy. He called Hogan while she was at her sister’s 50th birthday party, and simply asked, “Will you help me in my new role?” Together, they refashioned the company’s culture messaging.

“The first step in the transformation effort was to honor your past while you define your future,” Hogan said. “It was really important to look at all the things that were incredible about our culture and our history that we didn’t want to walk away from or dismiss. Yet we were clear that we needed to change from a bunch of ‘know-it-alls’ to a bunch of ‘learn-it-alls,’ and that was tricky to navigate because many people wanted a simpler narrative of ‘This is good; that was bad.’ It was really important for us to say, ‘This is how we have to evolve to be relevant in the future,’ versus being dismissive of the past.”

Hogan added: “We also spent nine months defining our culture around the ideas of empathy and learning, which was informed in part by the work by Dr. Carol Dweck on growth mindset. That was our overarching theme with key pillars under it, including being customer-obsessed, [being] diverse and inclusive, [integrating as] One Microsoft, and making a difference. The thing I tried to do was not to say that the people agenda is the HR agenda; it’s the business agenda.”

Priority 5: Model leadership excellence

The best CHROs are easy to collaborate with personally, and they create a function that is easy to work with. They earn respect and credibility because they embody the leadership behaviors that they expect of everyone else.

That starts with viewing an excellent HR function as table stakes, rather than the endgame of their role. They don’t harbor mediocrity within their team; they show an ability to rotate talent in and out, and they groom their team members to be fluent in business discussions with divisional or geographic leaders.

“First, if others in the company still think that your function has trouble hiring people or retaining people effectively or monitoring or addressing employee concerns, then it’s going to be hard for them to think that they should be inviting you in to talk about key organizational changes they need to make,” said Donna Morris, the Walmart CHRO. “Second, you better know your business and not fixate on shiny new programs. Focus instead on what’s going to help your business be really successful. If that means getting rid of some of your shiny programs, you better ’fess up and disrupt the very things you might feel wedded to. Third, you’ve got to role-model everything you’re asking every other leader to do. The bar for you in terms of people leadership is actually higher than the bar for everybody else. What’s your strategy in terms of attracting talent, developing talent, and managing performance? If you’ve got an employee survey, [HR] better not be the lowest on the totem pole in terms of organizational health. People should be envying how you lead.”

Susan Podlogar, the MetLife CHRO, and her peers who are reinventing the role of the chief human resources officer simply are not satisfied with the status quo. “Many people continue the same practices and benchmarking against others and say, ‘OK, that’s good enough, I’ll use it,’” she said. “We’ve got to redefine HR, and, most importantly, we’ve got to redefine HR against our business strategy, the future of work, and the future of the workforce. This is one of the most complex times to be in HR, but one of the most exciting times to be in HR. HR is in a very different place than it’s ever been, because we have practices that don’t fit anymore.”

Our goal in this analysis has not been to provide a rigid playbook for human resources. After all, the frameworks and approaches for doing the job must be customized to the particular needs of an organization. The ambiguity of the role is a challenge, but it is also an opportunity. The insights the CHROs shared above, and the five priorities we have identified, serve as a solid starting point for constructive conversations among HR executives, CEOs, and board directors.

“Many HR executives grew up in a world of process, and that is the world we’re leaving behind,” said Diane Gherson, who recently announced she would be stepping down from her role as IBM’s chief human resources officer. “So it’s important for CHROs to get out in front of that and get into the world of outcomes and particularly experiences that they’re creating — and that means reinventing pretty much everything they do.”

Author profiles:

- David Reimer is CEO and managing partner of Merryck & Co. Americas and executive editor of the journal HR People+Strategy.

- Adam Bryant is managing director of Merryck & Co., a senior-leadership development firm. He is the author, with Kevin Sharer, of the forthcoming book The CEO Test: Master the Challenges that Make or Break All Leaders, to be published in March 2021 by Harvard Business Review Press.