Thinking through the ethics of corporate journalism—before there’s a problem

Three simple strategies that should form the basis of your content playbook.

It’s been 50 years since survey respondents famously told Oliver Quayle that they trusted a news anchor more than any candidate running for public office. At the top of their list of “most trusted” people in America was none other than Walter Cronkite, who dominated the evening news ratings for a generation. In that turbulent era, defined by the Kennedy assassination, the Vietnam War, and Watergate, people tended to trust the news media—in particular Cronkite’s deft and steady delivery—more than most other institutions.

Today, we’re witnessing another shift in public trust, this time in the perception of the news media itself. For the second year in a row, “my employer’s media” beat traditional information sources (including media and government) as the most trusted news source in the Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual survey of 36,000 people in 28 countries commissioned by communications giant Edelman. In explaining the finding, CEO Richard Edelman reasoned that most people consider their employer’s media to be depoliticized and “honest.”

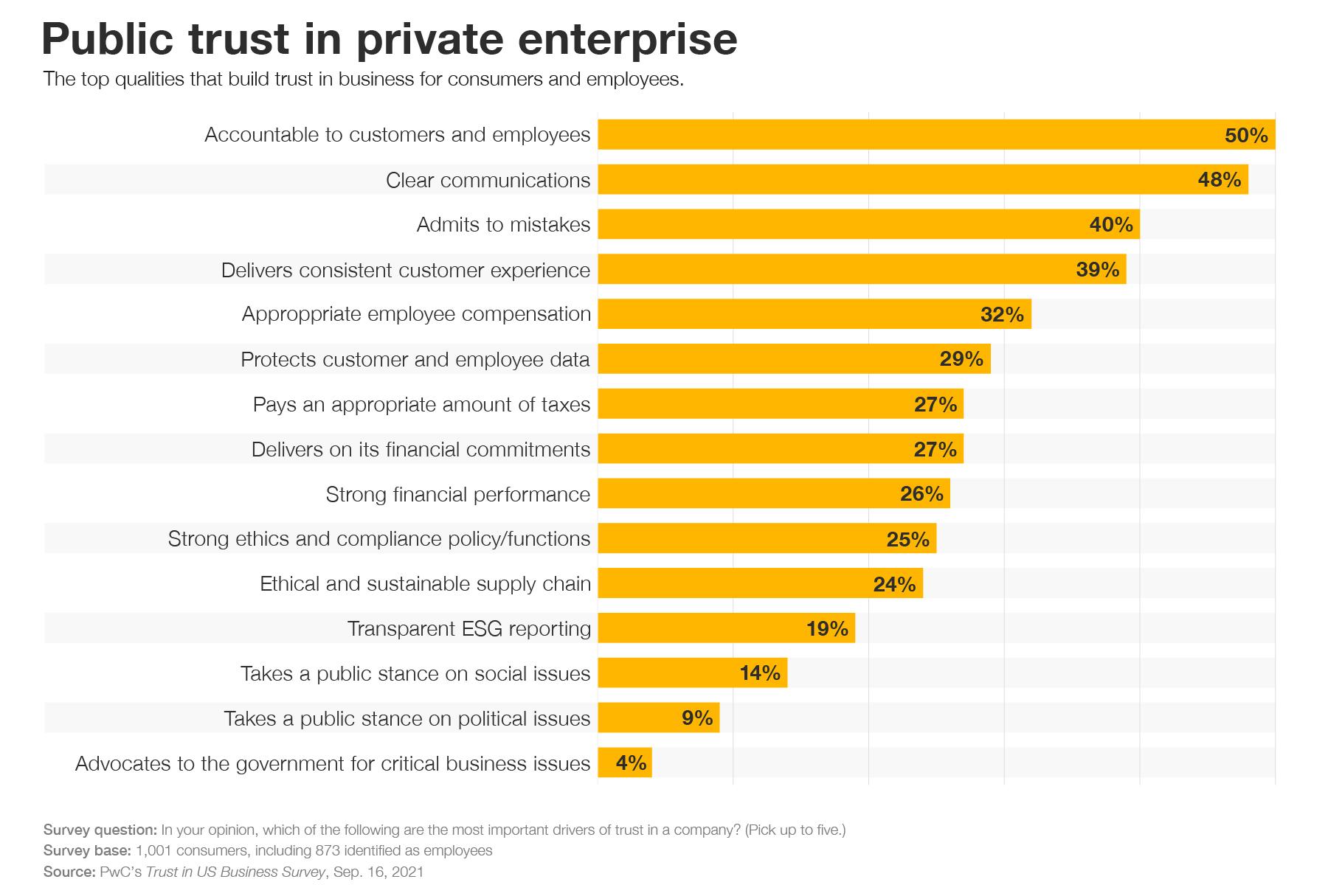

Other recent research bears this out. PwC’s Trust in US Business Survey, conducted in August 2021, found that people trust businesses as much as or more than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase in public faith has put pressure on companies to raise their game in communicating who they are and what they do. More than 75% of the 1,115 US adults surveyed in late 2021 by nonprofits Just Capital, Public Citizen, and Ceres said they wanted to see more corporate disclosures of business, social, and environmental practices, as well as the impact of those activities.

Such demand for clarity in the initiatives that companies are undertaking has given rise to so-called corporate journalism—a trend in which experienced writers and editors work on the inside of firms to create narrative-based, reportage-like content, often to augment broader public relations or marketing campaigns. (Strategy+business, where this article is published, can also be considered corporate journalism, produced by PwC.) When you factor press releases, blogs, and social media posts into the equation, companies can sometimes find themselves producing a lot of content without a coherent ethics strategy.

Ethical questions abound

For leaders navigating these crosscurrents, the challenge is delivering content that is fair and accurate while also advancing the interests of the organization. Though about 70% of global consumer-facing companies already have a content strategy to guide the formation of policies and practices for publishing content, many companies are still figuring out how to make their way through a thicket of ethical questions. Should an organization, for an example, proactively discuss controversies that would have been expedient to sidestep in the past? Should firms publish content that is accurate but not comprehensive, such as reporting on a corporate climate pledge that doesn’t note environmental shortcomings in other parts of the business? Should they invite opposing views and criticism? Should they openly admit and correct mistakes? And who within the organization makes the call if the audience for the content should desire information that clashes with the company’s corporate messaging?

Boston College associate professor Michael Serazio, who studies corporations’ efforts to promote themselves within traditional news formats and practices, says the profit motive is so powerful that it’s “unreasonable” to expect companies to become dependable truth tellers. “Would you trust Enron Magazine? Lehman Brothers Daily?” he asked strategy+business in an interview for this article.

Nobel laureate economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller would seem to agree, at least in terms of the motives inherent to modern companies, writing in their 2015 book, Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception, that “the economic system is filled with trickery, and everyone needs to know that.”

The question at the center of the debate is whether companies can thoroughly and honestly address the subject they should know best: themselves. “It’s a lot for a company to take on, but it’s doable,” author and former General Electric vice chair Beth Comstock told strategy+business. During her tenure at GE, the company hired journalists to give their content efforts more validity.

General Electric faced a public relations crisis in 2011 after the New York Times wrote that the company reported a tax benefit of US$3.2 billion in 2010 even though it had worldwide profits of $14.2 billion, including $5.1 billion from the United States. Eager to show that GE had, indeed, paid taxes, the executives debated releasing company tax returns. In the end “we shared bits and pieces,” Comstock said. “These things become so complicated.” Still, “it’s good to have the aspiration.”

But even leaders of venerable news companies become thin-skinned when they’re in the spotlight, sometimes arguing that people shouldn’t expect their organization to cover itself fairly—and wouldn’t believe the organization if it tried. Bloomberg News has a policy of not covering itself, which extended to founder Michael Bloomberg when he announced his US presidential run in 2019. Meanwhile, the movement for news organizations to hold themselves accountable with independent reader representatives or ombudspeople has largely petered out. Only a few still have such a representative, down from the 50 newspapers that had them in 1980.

In the main, corporate journalism fits a familiar pattern that also occurs when any new technology is introduced: it grows rapidly and becomes ubiquitous, and only then do companies begin to see and address the problems it creates. Though executives can’t predict the future, they can adopt a sound framework that will help them prepare for and respond to unexpected impacts. Here are three strategies that can help leaders develop a playbook based in candor.

Corporate journalism fits a familiar pattern that also occurs when any new technology is introduced: it grows rapidly and becomes ubiquitous, and only then do people begin to see and address the problems it creates.

Hire truth tellers—and listen to them. You can’t count on managers to rock the boat. Most are promoted as a reward for sticking with the company for a long time, creating a corporate culture that is inclined to avoid risks. Let the managers manage, and, separately, find some independent thinkers who know how to present information honestly, clearly, and engagingly.

It’s a tough job. “You’re never going to have the best perspective on your own organization,” ProPublica founding general manager and former president Richard Tofel told strategy+business. This is especially the case if the company is publicly traded and trying to parse securities laws’ disclosure requirements. Still, what Tofel calls “radical transparency” is “appropriate and pays real dividends” for companies with the courage to practice it. Tofel, a onetime assistant publisher of the Wall Street Journal who now, as a principal of Gallatin Advisory LLC, helps clients navigate the world of journalism, adds that “if there is a bad fact in the world, then people will eventually find it out.”

That’s why a broader ecosystem of experts and collaborators needs to be embedded into a firm’s publishing processes. Outside perspectives and expertise on fair and balanced reporting of information will go a long way toward building trust with consumers and placing societal need in line with the responsibility to grow revenues.

Engage with critics who have the public’s ear—and admit your mistakes. Few companies have the nerve to embarrass themselves in any form, let alone in their own media. For example, just 215 (23%) of 954 US companies surveyed disclosed that they conducted a gender pay gap analysis last year, according to a Just Capital study of transparency on the issue. Boards also typically swat away shareholder resolutions urging them to disclose direct and indirect payments for lobbying, even though 54 (84%) of the 64 largest institutional investors want to see it, according to the Center for Political Accountability.

It’s time to get over this reflexive secrecy and defensiveness. It’s a bad look, it’s counterproductive, and soon it might cease to be an option.

The Conference Board said that in 2021, publicly traded corporations saw “record support for shareholder proposals” calling for fuller disclosures about environmental and human capital policies, political activity, and governance decisions—and predicted the trend would “continue into 2022.” Earlier this year, the business research group said the growing public belief in stakeholder capitalism represents a “tectonic” shift driven by institutional investors that “face client pressure to invest and vote in a socially responsible manner.”

Serious critics can help a company improve itself. So why not seek them out and even give them a platform to discuss or respectfully debate their critiques, especially if those critiques are going to be heard elsewhere? Sure, some executives will object to seeing dissenting views in a company’s own media. But this is how outlets can earn an audience’s interest and trust—and distinguish their communications from mere propaganda.

Encourage question-asking. It’s hard to persuade the public to trust you if your own employees don’t. And though Edelman and others see growing public confidence in business, this faith appears fragile when you look at the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ reports of growing quit rates and Gallup surveys showing increasing employee disengagement.

Employee dissatisfaction is a complex problem that defies simple solutions. But one way to promote engagement and trust is to encourage employees to ask questions—the tougher the better—and then address their concerns via the company’s media channels.

Companies can do their part by assuring employees that they’re likely to be rewarded for asking relevant questions—and never have to fear that their good-faith queries will be dismissed as stupid, inappropriate, or a waste of executives’ time. Those that want to fully embrace question-asking can offer training, which is a strategy supported by the Right Question Institute, a nonprofit that encourages self-advocacy and what it calls “microdemocracy.”

Executives who promote question-asking might discover measurable benefits for their enterprises, in addition to promoting trust. At a time of fast and unpredictable change, it’s a way to ensure that people are up to date with new directions in everything from the design, building, and operation of tools to strategy, marketing, and brand storytelling. It can help to bust organizational silos. What’s more, question-asking may help companies “see things in a slightly different way, and the result of this may be new insights, new learning,” Joseph Stiglitz and Bruce Greenwald note in their 2015 book, Creating a Learning Society.

Acting with integrity

Recent research points to a historic moment for businesses. Consumers, employees, and other stakeholders expect companies to earn their trust by being honest, authentic, and transparent. If mistakes happen, leaders are now expected to commit to making things right, quickly. No longer can they tell the public whatever’s expedient in the moment.

Those accustomed to viewing trust as just a metric for the success of a self-serving brand or public relations strategy ignore the recent warning signs at their peril. They may not enjoy the soul-searching that’s needed to change their mindset or the hard work required to change their strategy and culture. But as Walter Cronkite used to say each night, “that’s the way it is.”

Author profile:

- David Lieberman is an associate professor in the graduate media management program at the New School. A former editor at Deadline.com and USA Today, he writes about changes in TV, movies, music, digital, and publishing businesses.

- The author thanks Carina Cozminschi for her contributions to this article.