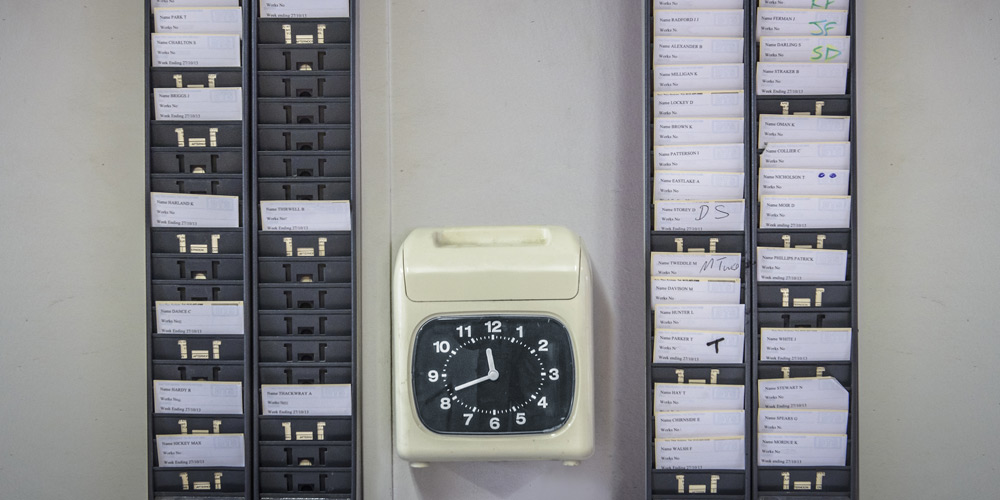

Clocking in, 21st-century style

In the era of telecommuting, what qualifies as “working time”? A new paper proposes a way to track employees’ hours on the job while respecting their time off.

In the digital age, the idea of taking work home has been given new meaning. The rapid spread of smartphones, apps, and wireless technology means employees can stay connected to work when they’re commuting, at home, or even on vacation. Gone are the days of punching a time clock. Now that email, text messages, and chat apps are just a smartphone tap away, the lines between personal and professional time have blurred considerably. And that was true even before the COVID-19 pandemic turned many people’s homes into their office.

Two years ago, Canada’s government commissioned an online survey about working time in the modern era; 93 percent of respondents said they thought employees shouldn’t have to respond to work messages outside working hours. The following response was typical: “I would love to see the government set a tone and limit work beyond normal working hours.”

Several governments have done just that. France, Italy, and Spain have passed versions of a “right to disconnect” law, protecting employees from repercussions if they don’t answer calls or emails outside office hours. Automotive firms in Germany have voluntarily adopted similar rules; Volkswagen employees, for example, can receive messages on their work smartphones extending only a half hour before or after their shift, and BMW compensates workers for reading and responding to emails at home.

Building on these attempts to modernize the concept of working time, a new paper by Tammy Katsabian seeks to provide guidance for firms and regulatory bodies on how to establish work–life boundaries for telecommuting in the 21st century. The author analyzed the latest legal, sociological, and business literature on the topic, including studies and surveys commissioned by government agencies, to propose a model that fairly compensates employees for working “off the clock,” while also respecting their right to free time. Her proposed solution relies on sensible surveillance using the smart tech that brought the issue to the fore.

Always on

Long before the advent of mobile technology, regulation of working time was considered “one of the most important objectives of labor law and collective bargaining” around the world. Research has demonstrated that work–life boundaries (or the lack thereof) have a significant impact on employees’ physical and mental well-being. When a workplace does not provide clearly defined breaks during the day or compensation for overtime, employees can suffer from exhaustion, dragging down their on-the-job performance and disrupting their home life. And an unhappy home life often leads, in turn, to distraction and a lack of motivation at work.

Although telework was introduced to give employees autonomy and flexibility — accommodating childcare, for example, or letting people work on their own schedule — the rise of mobile technology has resulted in many employees instead feeling pressured to be available or on call at all hours, the author writes.

And that’s just formal work. Checking email during a break at your child’s recital, posting on social media to promote the company’s product at bedtime, or answering a colleague’s WhatsApp message constitute more ad hoc types of telework. One scholar has coined the term time porosity to describe how leisure and labor are increasingly blended.

A recent study commissioned by the E.U. found that telework “leads to working beyond normal/contractual working hours, which often appears to be unpaid.” However, the European “right to disconnect” rules — both imposed and voluntary — may go too far in their one-size-fits-all approach, the study’s author writes. Dictating when employees can and can’t be on the clock appears to underminePDF the autonomy and flexibility that telecommuting is supposed to provide.

Breaking the bond between time and money

Why not abandon time-based payment models altogether, and shift to output-based compensation plans? The most famous attempt to do so was Best Buy’s Results-Only Work Environment (ROWE) approach, which has been adopted by many other firms and organizations. ROWE has employees set their own schedule, work at their own pace, and receive compensation based on their productivity.

But this approach has its drawbacks, Katsabian writes. Studies have shown that a too-flexible schedule can upend an employee’s work–life balance; without limitations or clear guidance, people take on too much or suffer from a fear of missing out. It’s worth noting that Best Buy no longer uses ROWE.

A too-flexible schedule can upend an employee’s work–life balance; without limitations or clear guidance, people take on too much or suffer from a fear of missing out.

The solution, Katsabian proposes, lies in the very technology that has ushered in the newest era of telecommuting. Because employees are glued to their laptops and smartphones, firms can track how much time — down to the second — they’re spending on work-related apps, docs, and messenger programs. When the work isn’t digital (such as when they read an offline report at home), employees can manually enter the extra hours.

To account for the increased time porosity of modern life, the author proposes that programs send a pop-up message to employees who appear to be working during their ostensible downtime, asking if this time should be calculated as work.

Many companies already track their employees’ productivity via technology, which also has downsides. This data can be used (or manipulated) by less-than-scrupulous firms to argue that employees aren’t working enough, a practice known as digital wage theft. That’s where the second plank of the author’s platform comes in: In situations in which there’s no obvious advocate for employees’ labor rights (such as a trade union), an employee representative should be appointed to liaise between management and workers, help negotiate overtime rates, and assist employees in customizing their working-time schedules.

In her book Pressed for Time, sociologist Judy Wajcman suggests that people don’t necessarily work more in the digital age, but they feel as if they do — because the clear boundaries between work and leisure time have all but disappeared. The new working-time reality is essentially a question of trust: Are employees working as hard and as much from home as they would be in the office? Are companies taking advantage of telework by implicitly demanding their workers be on call at all hours?

The way to resolve it, Katsabian suggests, is through transparency that takes everyone’s needs into account: Work done during leisure time is counted, and there’s an open dialogue between employees and businesses about how time is tracked and how it’s valued. One size doesn’t fit all.

Source: “It’s the End of Working Time as We Know It — New Challenges to the Concept of Working Time in the Digital Reality,” by Tammy Katsabian (Harvard Law School), May 12, 2020; forthcoming in the McGill Law Journal