Rocket-powered culture

The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s account of the birth of the American space program, offers a primer for business leaders on how to build a winning workplace.

All businesses have important things in common. Yet every business is also a subculture—a world of its own, with its own customs and character—and so every good manager has to be a bit of an anthropologist.

In that role, astute business leaders will tend to notice other subcultures whose strengths and weaknesses can shed light on their own milieu. How do these cultures maintain cohesion while accommodating change? How are hierarchies established? How are values transmitted? Which elements of culture contribute the most to meeting the organization’s goals?

There are many reasons to read The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s captivating account of the birth of the American space program, but an especially good one in this context is how effectively it captures the power of culture in an enterprise. In this case, it’s the unusual subculture prevailing among test pilots who pushed the frontiers of jet aircraft, often at the cost of their own lives, in the decades after World War II.

At the heart of Wolfe’s great story is change: at some point, space travel became the focal point of progress in flight—and the key to status in the world of post-Sputnik aviation. This change provides the thrust that powers The Right Stuff, which offers a fascinating case study for anyone concerned with business culture, technology, and the management of people who are for one reason or another indispensable.

The book was a hit when it was published, in 1979, and its style reflected Wolfe’s aim of reinventing long-form journalism by using a broader palette of literary skills in a more vivid, less formal style. It was an approach well-suited to its colorful subject: a group of men accustomed to taking colossal risks, dancing coolly on the edge of catastrophe, and making split-second decisions in an environment where mistakes can easily lead to a grisly death.

It was an extremely risky and poorly paid job, but glorious. And the pilots were sustained by an all-consuming, immensely powerful military subculture that dictated almost every aspect of their lives. In many ways, it was as far from today’s typical workplace culture as a tribe of hunter-gatherers living in remote isolation would be. The protagonists of The Right Stuff were white Protestant American men whose macho stoicism has all but gone the way of the dodo bird in contemporary culture. There was even a strong Calvinist strain to the so-called “right stuff,” the combination of daring, skill, and sangfroid that gave the book its name: Wolfe implies that, like grace, it was something that you couldn’t acquire, but that you tried at all times to exude, as if to prove your rightful place among the elect.

It was a different world, and these were unusual people. Yet the shift from supersonic flight to outer space that is the book’s focus brought challenges for the pilots and for the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) that, broadly conceived, will be familiar to anyone in the world of business today. Underlying these challenges was the extent to which new technology upends old hierarchies and creates new power arrangements.

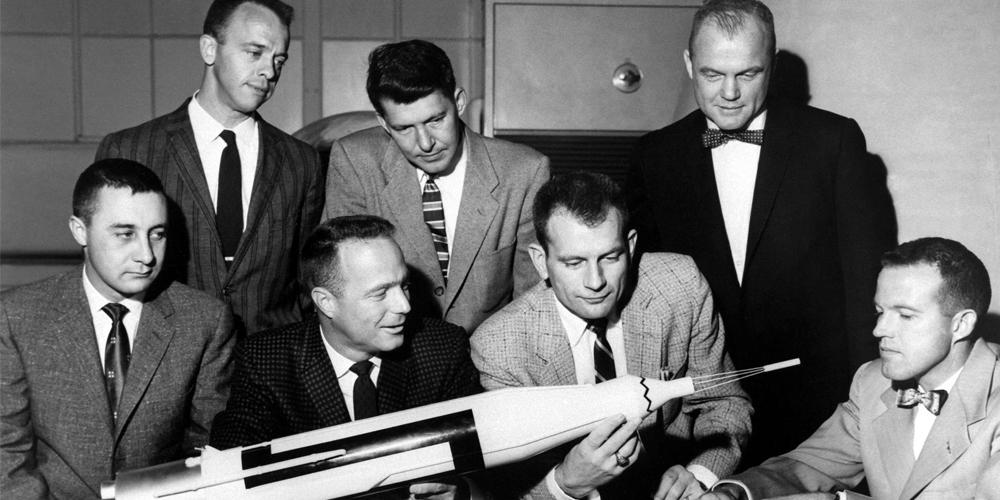

Before the race for space, the test pilots were the top dogs in the realm of aviation, and when the space program was launched, it seemed natural to select the first seven astronauts from among them. But the plan was for these extraordinarily confident and skilled men to function as mere human guinea pigs, with no control over the giant missiles they were riding into the heavens. Not only were they reduced from pilots to passengers, but in this topsy-turvy new world, the scientists they had once patronized suddenly became the top dogs.

A whole new civilian bureaucracy grew up around them, complete with congressional support, a growing constituency, and a culture of its own to create. For political reasons, NASA’s civilian leaders turned the astronauts into heroes even before their first spaceflight. Fueled by the new medium of television as well as the new space program, the astronauts’ newfound importance enabled them to turn the tables on the bureaucrats and scientists who had seemed to regard them as little more than lab rats.

The Right Stuff demonstrates that, in certain kinds of enterprises, stars can acquire great power, especially if the organization itself makes it possible for them to shine. The astronauts, once anointed and publicly promoted, soon dug in their heels over some of the experiments they found onerous—and that was just the beginning. There was no way for the pilot to open the hatch of the original Mercury space capsule, for example, but that soon changed as a result of pilot pressure. The astronauts also won manual controls in the capsule, just in case. Those controls became a lifesaver when Gordon Cooper, the last of the seven to go into space, brought the capsule down manually after its automated systems went haywire. For a while, that made him almost as big a hero as John Glenn, whose previous orbital flight had turned him into a national icon. Glenn’s star shined so brightly that even James E. Webb, NASA’s politically astute inaugural chief, couldn’t make him do anything he didn’t want to. None of this would surprise LeBron James or Tom Hanks.

The Right Stuff demonstrates that, in certain kinds of enterprises, stars can acquire great power, especially if the organization itself makes it possible for them to shine.

Early astronauts did not emerge from a therapeutic workplace culture; on the contrary, there was no talk of feelings or fear, and Wolfe claims the laconic, vaguely Appalachian tones affected by many commercial jet pilots can be traced back to Chuck Yeager, the dean of the era’s test pilots, whose unflappable drawl came with his West Virginia roots.

But projecting calm is almost always worthwhile. And other “right stuff” practices have caught on, too. The pilots’ reliance on checklists only increased during space flights, when they had long lists of experimental and other tasks to complete. Since then, the surgeon and author Atul Gawande, among others, has advocated more checklists in medicine. “The pilot’s checklist is a crucial component,” he observed, “not just for how you handle takeoff and landing in normal circumstances, but even how you handle a crisis.”

When Glenn was instructed, in preparation for his orbits of the earth, “to radio back every sight, every sensation, and otherwise give the taxpayers the juicy stuff they wanted to hear,” that went contrary to the strong fighter-jock taboo against “nervous chatter” in radio communications. That taboo promoted crucial focus—and, like checklists, has found its way into healthcare. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for example, has urged operating room staff to “postpone nonessential conversation until surgery is finished.” It even cited the federal “sterile cockpit” rule, which bars “engaging in nonessential conversations” during critical flight activities.

Creating and nurturing the right subculture can go a long way toward building a successful enterprise. But the rise of remote work, like the advent of space exploration, poses new challenges for the culture of business—and for the many subcultures that give character, meaning, and a competitive edge to the workplaces that sustain them.