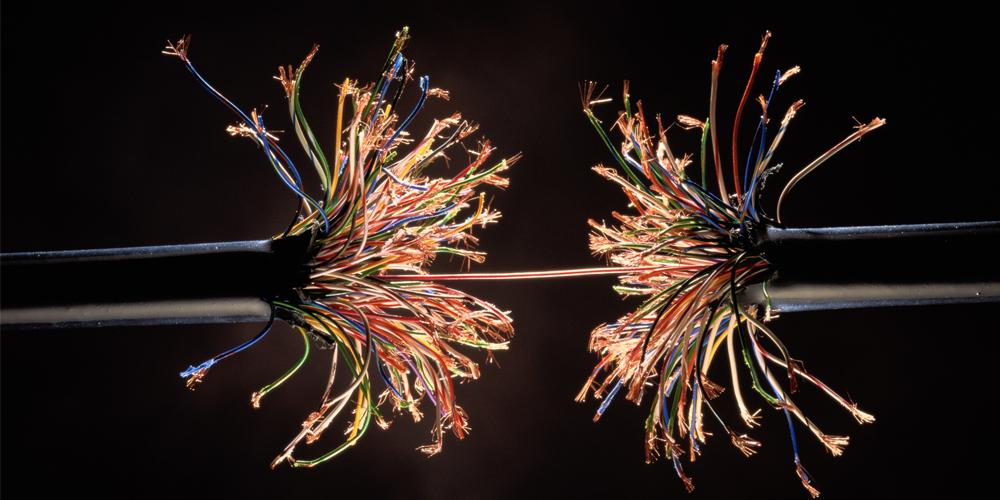

Technology alone won’t solve your organizational challenges

Master the fundamentals of organizational performance before you deploy fancy tools that may magnify dysfunction.

I recently participated in an online open innovation session on the future of work hosted by Everything Omni, a UK-based group aiming to “future-proof work and the workplace for the uncertainty of today.” I was quickly in over my head. Not because of the content. That was provocative yet approachable. I found myself overwhelmed by the collaboration tools, namely the virtual whiteboard. People were moving ideas in, out, up, and down while I was still trying to make sense of the dashboard. I was suddenly a stranger in a strange land.

Sure, a big part of me was longing for face-to-face interaction and the tactile comfort of sticky notes and erasable markers. But the uncomfortable experience made me reflect on the innumerable models, methods, and tools introduced in recent years to revolutionize the way we work. To wit: one problem facing organizations is the lack of organizational alignment around why these new technological innovations are so mission-critical. Unclear purpose and the lack of comfort and expertise with the what, where, when, and why of work can cause slowdowns, misunderstandings, redundant work, and one-off work-arounds. These and other frictions can add distraction, inefficiency, and unpleasantness to the work experience—and may contribute to burnout as well.

As we debate grand philosophical questions around the future of work, perhaps it’s also time to devote rigor to the fundamentals of organizational life, whether in the office, fully remote, or something in between. Agreeing on well-defined and widely practiced norms that mitigate unnecessary complication and conflict is essential for a desirable and productive workplace. Before expecting whizbang technology to create workplace nirvana, organizations must explore the cultural norms and core operating principles and practices that foster or confound productivity.

In my experience, misalignment and dysfunction arise when three fundamental building blocks of organized activity are not taken seriously: teams, meetings, and communication. Each element is interrelated and highly complementary. For example, a high-functioning team is inherently better at communication and more productive during meetings. In other words, deficiency in one area can derail the others.

Teams

I have never encountered an organization without teams. Some see them as a cure-all. Yet, a recent Harvard Business Review article by organizational psychologist Constance Noonan Hadley and organizational behavior professor Mark Mortensen points out the historically poor performance of teams. The authors note that while teams have long struggled to fulfill their promise as an organizational form, they face especially high hurdles today, in part because organizations keep forming teams without a clear idea of their purpose, how they should be structured and governed, and what expectations members should have for their individual and collective roles and responsibilities. For their part, Hadley and Mortensen propose “co-acting groups,” an alternative team concept in which participants share a goal and work independently but gather occasionally. (Think coders, writers, and designers who contribute to a website redesign without the formality of a rigid team structure and meetings.)

Before expecting whiz-bang technology to create workplace nirvana, organizations must explore the cultural norms and core operating principles and practices that foster or confound productivity.

Whatever your organization’s preference for team building, it should be carefully selected from a range of options, and it should be clear to everyone why the firm chose one particular structure over another and what’s expected of everyone participating. Start with desired outcomes and cultural norms, then articulate principles to empower action, and, finally, provide the skills and tools needed for success.

For example, I encountered one organization that committed to creating and formalizing a high-quality team culture. In the model they created, a cross-functional team required a charge, a charter, and a champion. The charge precisely defined the challenge the team would tackle. The charter outlined membership, expected duration, time commitments, decision-making authority, and other governance issues. The champion was a person with sufficient positional power to do something with the team’s work product. Though initially cumbersome, the requirements ensured clarity of mission and the rules of the road, along with some assurance that the work would not be a performative exercise with little impact. When it worked, it was the embodiment of the adage “slow is smooth and smooth is fast,” which is another way of saying that doing the hard work on the front end ensures smooth functioning later on and ultimately gets you to your destination faster.

Meetings

Working-group configurations are just the beginning. Meetings are another. I have written about meetings before, and countless others have written pieces on how to have better ones. Still, people chafe at unfocused and unproductive gatherings. The expectation that humans have an instinctual ability to organize and facilitate group work is belied by ample evidence that they do not. What is needed is a commitment to build the skills necessary to execute meetings well. There is no shortage of models, advice, and training for doing so.

Even in the most forward-thinking organizations, people want to know what a meeting is supposed to achieve, what their role is in that meeting, and if gathering people around a table or their screens is the most effective and efficient way to get to the desired outcome. Is there a decision to be made? Or is the purpose information sharing? Have people been given the chance to opt out if the above points are not clear? Asking these questions can serve as a rapid diagnostic for what you are getting right—and wrong—in your meetings. Poorly run meetings sap energy and breed mediocrity.

Communication

Daily communication is yet another area ripe for improvement. Long ago, Procter & Gamble invested in training its managers to craft concise, informative, and compelling one-page memos. Later, Amazon adopted the six-page memo as the mandated alternative to slide decks. I favor two pages as a good balance of brevity and depth, but no matter the length, limiting it begets discipline in both writing and thinking. Should there be exceptions? Of course. However, veering from the norm should be an intentional choice made for specific reasons. The core skills of clarity and concision will still apply. Picasso’s mastery of draftsmanship fueled his confidence and freed his mind as he ventured into abstraction.

Even if your organization relies upon short bursts on a messaging platform, each note should achieve the greatest effect. Though texting has become ubiquitous, for example, National Public Radio reported that most people do not text well. Define what “good” looks like in your chosen medium, and foster best practices.

Once upon a time, there was an administrative layer in organizations that competently handled many of these tasks. Known then as secretaries and now as administrative assistants, these individuals could manage schedules, create agendas, take notes, organize files, and so much more. Yes, there was sexism in their selection and pay, and the work was sometimes viewed as simple, beneath the talents of high-powered managers. Yet having people who understood the purpose of those seemingly mundane tasks and executed them well ensured consistency and quality, mitigating friction and fostering flow in the system.

Now, trained administrative support has disappeared for all but the most senior executives. The tools have been democratized so that each person does more and more for themselves, even if they do not do it particularly well. The savings from eliminating admin positions are easy to quantify, while the cost of the resulting inefficiency and frustration is far more difficult to pin down, though no less real. Earlier changes in organizational technology and protocols were incremental, and the comfort with in-person traditions made it easier to mask cracks in the system.

The current shifts underway are more sudden and dramatic. With distributed teams and hybrid work arrangements, even the most basic necessary skills and configurations are shifting. As Constance Noonan Hadley, who co-wrote the article about teams mentioned above, told me, “We have to ask how we optimize for a new world of work, because it is happening. I know from conversations with my executive students that there is a tension between how we think work is happening and what is actually going on. Organizations must adapt to resolve it.”

Unless your organization has embraced agile or lean methodologies, or made a radical leap to an alternative model, such as sociocracy, that forces reconsideration of the fundamentals, you are likely carrying a lot of unexamined baggage. Accept the need for change, and banish prior assumptions. Work-group structure, meetings, and communication are great places to start. Try these five steps for spotting the snafus that may be hobbling your organization.

Articulate your “center of effort.” Identify the activities that engage employees the most and in which the collaborative work is essential to business objectives. Have an open, democratic conversation to remove the distortions that come with a top-down view. Be open and honest about what’s working and what needs to change. Consider incorporating collaboration in key performance indicators (KPIs) and reward structures.

Start with the small stuff. If rambling meetings are a problem, for example, require an agenda and time limit for each gathering. Stick to your plan for at least three to six months to ensure you get over the awkward early phases of adoption.

Equip people for the “how.” Make sure your people understand the methodologies, processes, practices, and new tools you’ve chosen. Go beyond a three-minute video tutorial. The team-centric company mentioned above invested in professional-facilitation training for every manager likely to lead a team. The skill-building sessions also demonstrated executive commitment to getting teamwork right. Go for proficiency, not simple competence.

Lead by example. Show your employees that an old dog can learn new tricks. Tackling an unfamiliar process or application can be an opportunity for relationship building and modeling a growth mindset—for example, letting yourself be mentored by a more junior staff member.

Establish feedback loops. Regularly practicing “stop, start, continue”—an organization model for eliciting meaningful feedback—creates an ongoing process of engagement, assessment, and change that will keep practices fresh.

How to get started? Convene your group around a virtual whiteboard—just make sure everyone knows how to use it.