What’s Going on with Wages?

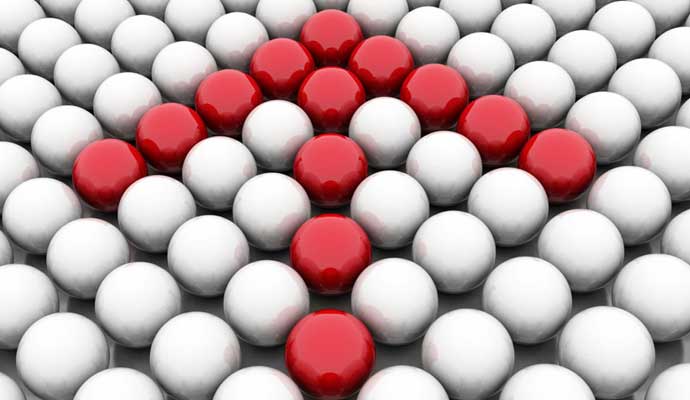

As the labor market continues to change, base pay is rising much more quickly for the bottom 20 percent of earners than for other workers.

We live in a superstar economy. Those who are really, extremely good at their jobs in rarefied domains — sports, acting, coding, social influencing, money management, running companies — get paid disproportionately well. For everybody else, however, wage growth in an age of technological change and sluggish economic expansion has been difficult to come by. It has come to be accepted as something like a natural law in the economy. And it all has to do with the way the vast global market rewards size, scale, and outlying performance in the 21st century.

Rewarding superstar players with outsized pay is a pretty strange and ineffective way to run an organization or an economy. Of course, a superstar can help boost performance and bring in crowds. But most entities function as teams. Steph Curry needs four other players on the basketball court — and another eight on the bench — to perform his magic. If you pay a movie star US$10 million to appear in a film but scrimp on all the other necessary professionals — scriptwriter, grip, set designers — you’ll likely end up with a mediocre product. And in many enterprises, from retail to restaurants, from manufacturing to sales, hundreds of capable people need to work in concert in order for the organization to be effective.

But there are some signs that this apparent order is being upset. In a recent post on Bloomberg, Matthew Boesler examined the rate of wage growth in the U.S. by different quintiles in 2017 compared to 2007 — the point in the previous economic cycle when pay was rising the fastest. And he found an inversion of what seems to be the order of things. “The bottom 20 percent of workers by average industry pay are seeing significantly faster wage growth now than they were then,” he writes. For these people, wages are growing at an annual rate of about 4 percent — much more rapidly than the pace at which they’ve been rising for much of this long, slow expansion.

More significantly, the figure is substantially higher than the growth rates for those in the top four quintiles. And for the top 20 percent of earners, the income growth rate has actually fallen in the past year. (Don’t shed a tear for them — they’re doing just fine.)

Here’s the thing. The shape of the labor market is constantly changing, as powerful structural forces (the weakness of unions, the advent of technology) interact with cyclical forces (the supply of labor, the number of open positions). Sometimes, those forces can conspire to keep wages down. If there are a lot of people out of work at the same time an industry is able to use automation to reduce the need for labor, then you would expect really weak wage growth.

By contrast, if there’s growing and intense competition for workers in an industry at the same time that companies aren’t finding it all that easy to replace labor with machines, then you’d expect something of a squeeze. It’s harder to hire workers, and companies really need to add people because they can’t figure out any other way to get the work done.

And that may be what is happening today. Readers of this column should know the familiar litany by now. The economy has been on a huge job creation streak since 2010, creating jobs for 85 straight months. The unemployment rate is 4.1 percent. There were 6.1 million open positions in the U.S. at the end of September 2017, close to a record. There is essentially one unemployed person per job opening, compared with nearly seven in 2009.

Of course, a superstar can help boost performance and bring in crowds. But most entities function as teams.

You’d figure that with these types of numbers, companies would be working furiously to invest in the machines and software that can do the work of humans. And they are. But technology and automation aren’t equally distributed across industries. There are assembly lines in factories that can put together cable modems without human intervention, to be sure. But plenty of key industries are just as human-intensive as they’ve always been.

Boesler notes that “the lowest 20 percent of earners are most likely to work at places like restaurants, general merchandise stores (think big-box retailers), grocery stores, or businesses that provide care to the elderly and disabled.”

Not coincidentally, these are industries in which labor-saving or labor-eliminating devices have yet to be rolled out at scale. Sure, some fast food chains are experimenting with kiosks that take orders. But the typical restaurant continues to rely overwhelmingly on waiters and chefs to prepare and serve meals. The same holds for stores, which rely heavily on human labor to keep the shelves stocked, wait on customers, and process returns. And although the burgeoning home healthcare industry may use technology to monitor patients, it still has to send out legions of nurses and attendants to check on clients and care for them.

There’s one more factor to be considered. In several states, the minimum wage has been raised in recent years. Again, those in the lowest quintile are more likely to earn the minimum wage, or to work at companies or in industries in which the official minimum wages serves as a floor. When that floor rises, it impacts those in the bottom quintile in a way that it won’t affect higher earners.

Add it all up, and the labor market seems to be ordered in a way in which those at the bottom of the income ladder are more in demand than the superstars at the top.