Asia-Pacific’s rebalancing act

As the power of traditional drivers of growth fades, companies need to develop more resilient and rebalanced supply chains to keep the region moving forward.

When Japanese hygiene and household products maker Unicharm in 2020 launched a baby diaper containing an anti-mosquito capsule to help prevent insect bites in the humid climates of Malaysia and Singapore, it was a noteworthy example of consumer product innovation.

The company now plans to apply what it has learned in product development for these two Southeast Asian markets in a substantially larger arena: India Unicharm is expanding into the world’s second most populous country to capitalize on the rapid growth of India’s middle class, while expanding beyond China, a more established market where Unicharm faces intense competition.

Meanwhile, in Bekasi, outside Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, Hyundai is busily completing construction on a US$1.5 billion automotive assembly plant. When it opens in the second half of 2021, it will represent the South Korean carmaker’s first manufacturing presence in Southeast Asia. One of the motivations of expanding production beyond China, where Hyundai has made vehicles for years, is to leverage the maturing supplier and manufacturing capabilities in Indonesia (population: 270 million), one of the most promising markets in Asia-Pacific.

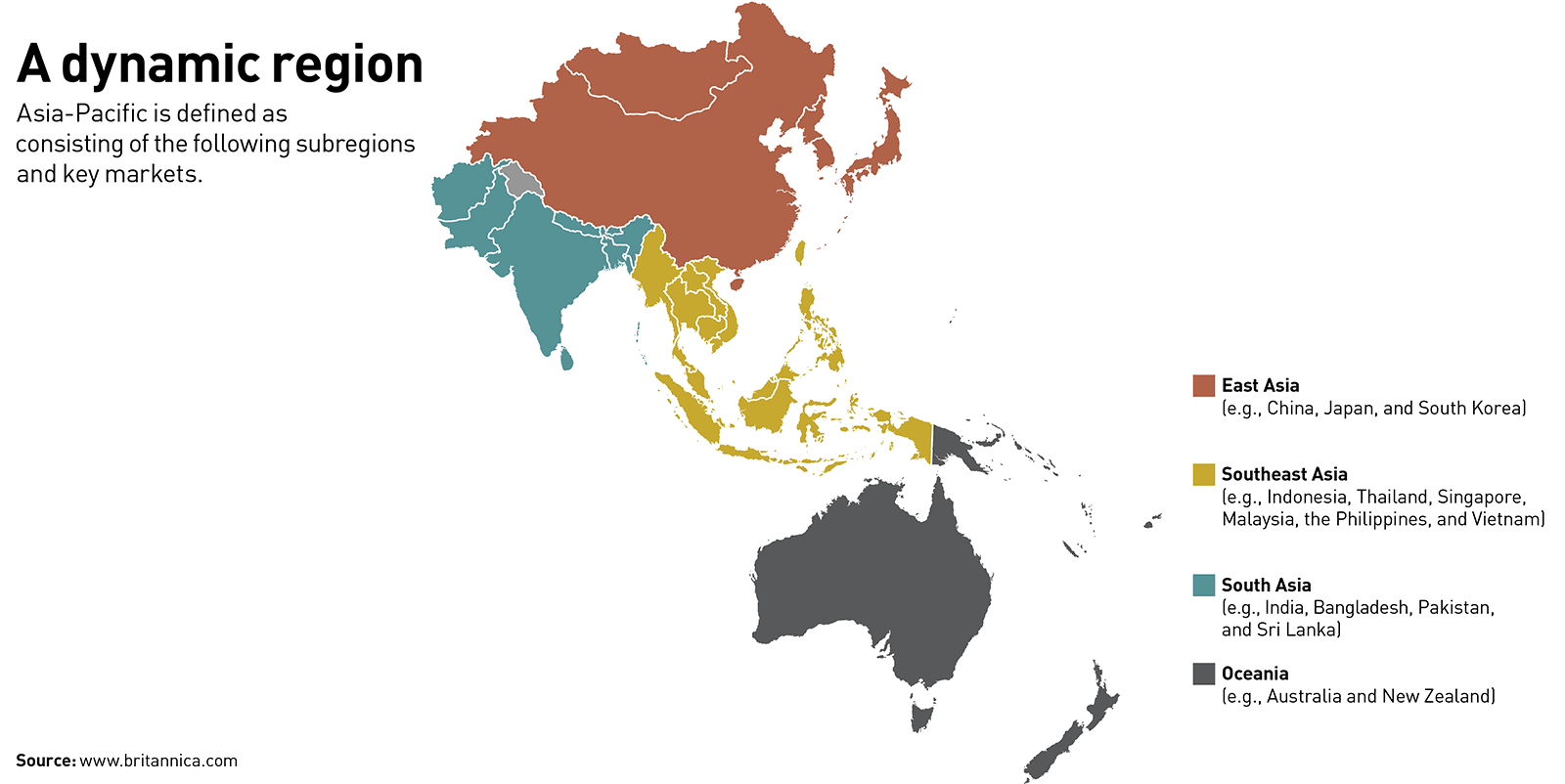

These moves, and many like them seen throughout the region, reflect the powerful supply chain and consumer trends that were brewing before the COVID-19 pandemic. These trends include the growth of consumer markets across Asia-Pacific (see map) and a desire by some companies to diversify supply chains and manufacturing beyond China, due to the country’s increased costs and tighter regulations, in what has been called a “China plus” strategy. The growing maturity of local suppliers in other parts of Asia-Pacific is further supporting these companies’ decision to expand their manufacturing footprint to new territories, such as those in Southeast Asia.

This rebalancing has been accelerated by a series of disruptive events, most notably the rising frequency of transpacific trade disputes and the pandemic. These twin forces have pushed companies to confront how they rebalance supply chains and manufacturing footprints to take advantage of changing consumer and supplier trends, and, in the process, to build in resilience so that they can weather inevitable future disruptions.

Historically, this region has shown a great capacity to absorb and ultimately overcome powerful shocks and barriers to development. In the past two decades, setbacks such as the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak of 2003, environmental disasters including the Japanese earthquake and ensuing tsunami in 2011, periodic political and social instability, and, in some countries, persistently weak infrastructure haven’t put a halt to the region’s impressive growth trajectory. However, the fundamentals that have enabled its growth and prosperity to this point are eroding and, as a result, so is the region’s capacity for handling change.

“Advanced Western economies have for a long time invested in manufacturing and exporting through Asia-Pacific, leading to the economic growth of many Asia-Pacific economies,” notes Tom Rafferty, Asia regional director of the Economist Intelligence Unit. “However, the recent trade tensions and the ongoing pandemic have caused a shift in this model, making it imperative for Asia to now look inward and collaborate regionally to foster growth.” Indeed, the supply chain arrangements that have helped power Asia-Pacific’s export-driven economies for the past quarter century now need to focus more on the region itself, while continuing to serve demand in Europe and the United States. That is because demand in those two markets has weakened just as markets across Asia-Pacific have matured to the point at which they justify being served in their own right.

The effects of these shifts are unfolding as the region tries to recover from COVID-19. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted in January 2021 that after falling by 1.1 percent on average for 2020, the gross domestic product (GDP) for developing Asian economies will grow by an impressive 8.3 percent in 2021. Yet that recovery is expected to be uneven, widening economic divides in the region. The IMF warned that social cohesion could even be undermined by the worsening of inequality as low-income workers are affected by pandemic-induced joblessness and the resulting drop, albeit a short-term one, in disposable incomes.

Taken together, these developments show that Asia-Pacific, home to 60 percent of the world’s population, is at a crossroads. Over the past several decades, Asia-Pacific has provided one of the great growth stories in human history. In the 60-year period ending in 2020, the region’s share of world GDP tripled to nearly 40 percent. The area now accounts for more than one-third of global merchandise trade and is home to four of the world’s 10 leading manufacturing countries (China, Japan, South Korea, and India). But the region urgently needs a new growth story, one that leaves behind the passive growth of the past and embraces new strategies from business, governments, and society to fulfill its potential as the effects of COVID-19 start to recede. Such strategies will also equip Asia-Pacific to ride out future disruptions.

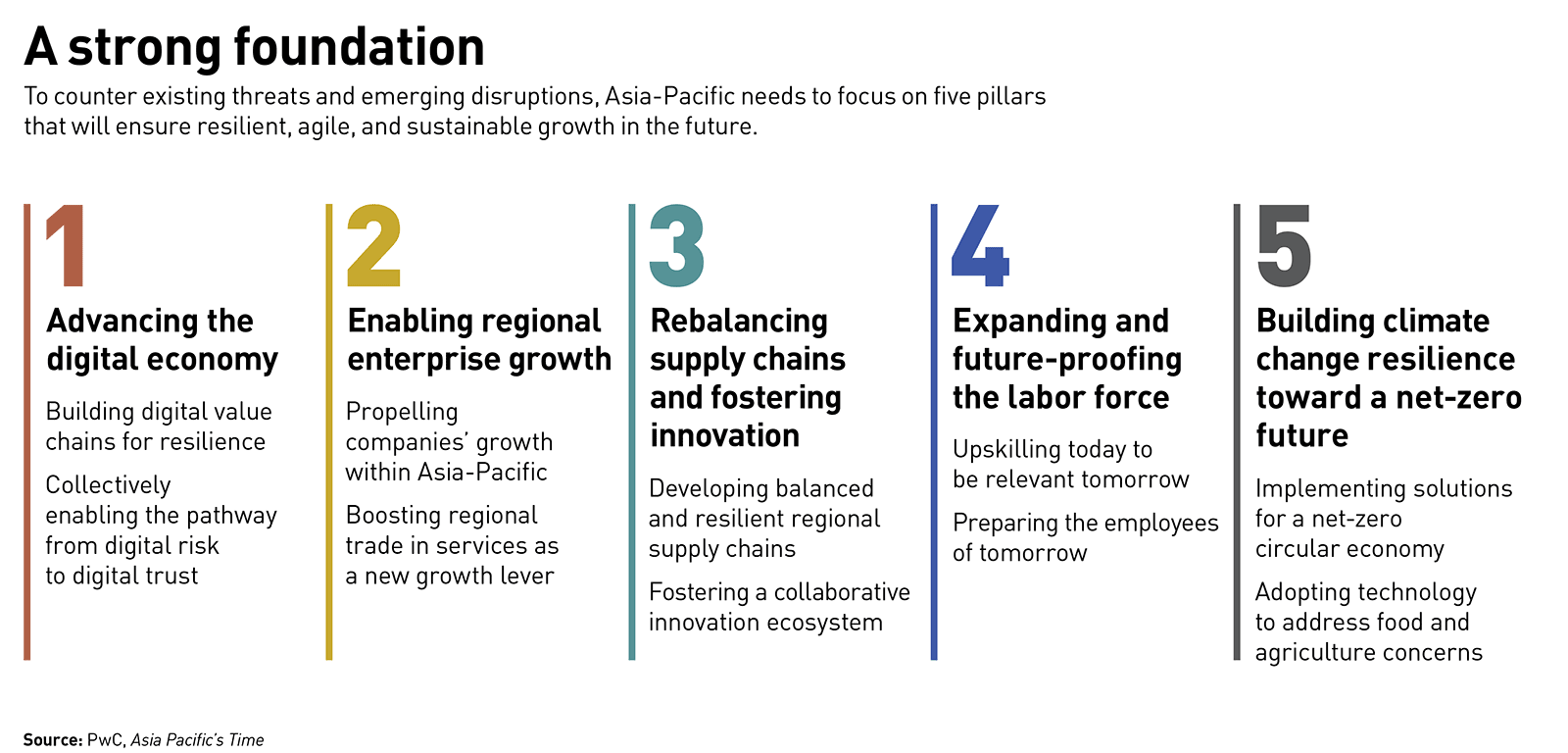

We believe this new approach, detailed in our report, Asia Pacific’s Time, should focus on building rebalanced and more resilient global supply chains and further enabling the regional growth of homegrown Asia-Pacific businesses. These should be supported by complementary growth pillars, which include: advancing the digital economy, fostering innovation, expanding and future-proofing the labor force, and building climate change resilience toward a net-zero future (see graphic below).

Rebalancing supply chains

For many industrial manufacturing and consumer goods companies, having lean, efficient global supply chains has long been a priority. This efficiency has generally involved managing a relatively small number of large suppliers while reducing lead times and increasing profitability. But domestic demand across Asia-Pacific is increasing rapidly. Rising income and urbanization have spurred the growth of a vast middle class, which now represents 70 percent of the region’s population, up from only 13 percent in 1980. (The Asian Development Bank defines middle class as households with per capita expenditures from $3.20 per day to $32 per day, in 2011 purchasing power parity.) In October 2020, Euromonitor projected that Asia-Pacific would record the fastest growth in retail sales worldwide over the coming years. The availability of a network of maturing suppliers has created the opportunity — and the need — to rebalance supply chains to bring suppliers and manufacturing companies closer to where consumption is happening, and doing so in a more resilient and reliable manner.

The beginnings of such a rebalancing were already evident before the emergence of trade tensions and then the pandemic, but it has taken these events to spur more business leaders into action. “In line with these changing trends, we are focusing on realigning our footprint to lower trade and other operational costs, mainly by leveraging our presence to new regional locations to expand markets outside China,” said Allen Huang, chief executive officer of Merry Electronics, a Taiwan-based manufacturer of electroacoustic products. “Expansion to Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand and Vietnam has been evaluated in this regard, while maintaining our presence within China to serve its large local market.”

Rebalancing is one part of the calculus. The other is resilience. COVID-19 revealed the brittle nature of existing global supply chains. When lockdowns were instituted, the overconcentration of supply networks in a few countries (such as China) led to significant disruptions in production and the movement of goods. That, in turn, created inventory shocks throughout the just-in-time inventory management systems that are so prevalent. Transport and shipping constraints caused by roadblocks and quarantine measures also led to order backlogs, material shortages, and price increases. Together, these developments highlighted a need to shift away from a cost-driven, globalized approach to a regional one that places a premium on finding reliable, resilient network partners.

Thomas Knudsen, the Singapore-based managing director of Toll Group, an Australian transport and logistics group, has firsthand experience of the effect of COVID-19 on supply chains. “Many of our customers have begun the process of diversification to build more resilient supply chains and to mitigate risk,” he said. “The impacts of the pandemic have certainly been a stark reminder that when one part of a supply chain network is compromised, all elements can become vulnerable.”

Companies have started focusing on building greater redundancy into their supply chains by ensuring inventory levels in case of future disruptions. Doing so enables companies to guarantee continued delivery to key customers. At the same time, they are looking for alternative regional suppliers and delivery partners. This approach points to a broader requirement of diversifying manufacturing and supplier portfolios to reduce dependency on a limited number of markets, and ensuring that new suppliers in Asia-Pacific meet companies’ quality standards and are capable of withstanding disruptive events.

Companies now need to go further as they develop regionally integrated supply chains. Businesses need to identify and prioritize challenges in the supply chains that they can address with process improvements and digital solutions. Targeted redundancy can be added for high-value premium segments, ensuring just-in-case delivery. This enables businesses to serve their most essential customers during times of crisis, while offering better service to all during normal times. One path to building better customer experience and driving profitability lies in establishing digitally enabled supply chain hubs, creating new data exchange mechanisms and supporting regional partners in technology adoption. The sophisticated supply chain hubs are also known as control towers, because they allow the central management of regional production plants and supply networks. Technology-enabled regional supply chains will help businesses better manage procurement, production, and distribution networks to achieve greater resilience. Such supply chains offer improved visibility and responsiveness. When participants have access to real-time data through digital platforms, companies can plan for possible problems, monitor performance, and react to emerging challenges.

Although certain markets, such as Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Indonesia, may benefit from such a rebalancing of suppliers, others, such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and South Korea, are well positioned to play a significant role in how these regional activities are managed. Advanced trading and logistics centers including Hong Kong, Singapore, and Busan in South Korea could develop into such regional supply chain hubs. Hong Kong launched a $44.5 million program in early 2020 to extend subsidies to third-party logistics service providers to adopt new digital technologies. The South Korean government has allocated $132 million to commercialize autonomous technology for ships. The Port of Busan, South Korea’s largest port, which in 2019 invested in a blockchain-based inter-terminal transportation system, is leading an initiative to develop a smart port logistics system.

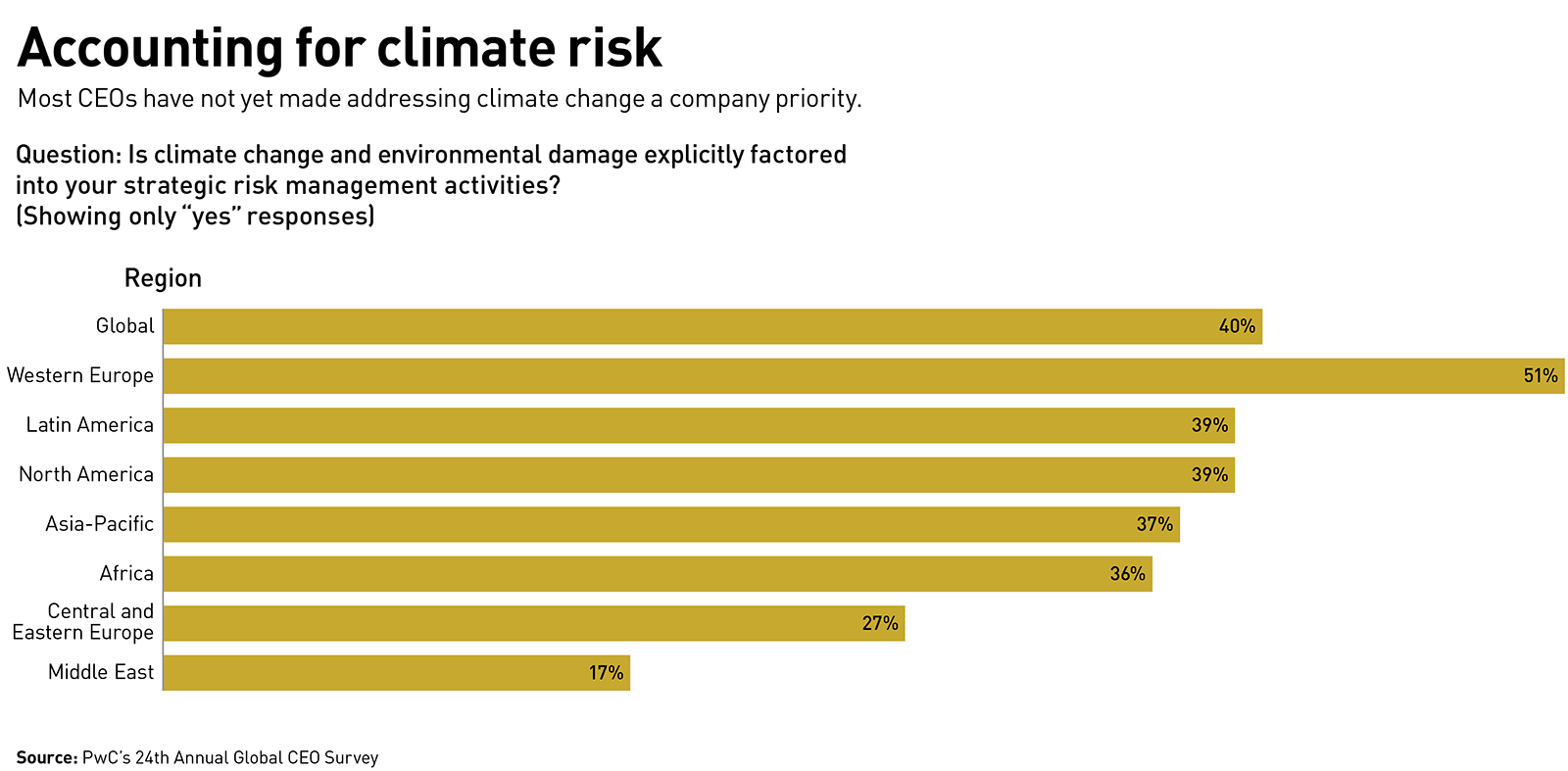

As companies realign their supply chains and manufacturing footprints, there is also a need to do so with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations in mind. Asia-Pacific accounts for the world’s highest share of carbon dioxide emissions, and the relentless pace of urbanization and consumerism continues to increase emissions and waste. However, according to PwC’s 24th Annual Global CEO Survey, only 37 percent of CEOs in Asia-Pacific have considered climate change within their strategic risk management activities. That’s below the global average of 40 percent, and much lower than the leading region, Western Europe, at 51 percent (see chart below). This needs to change, and ESG now needs to be incorporated within the performance criteria for all parts of the supply chain in Asia-Pacific, including selection of suppliers and assessment of new locations for manufacturing. Shifting toward a net-zero future for such a vast and diverse region will require concerted efforts from multiple stakeholders — governments, society, and businesses — across sectors such as energy, utilities, agriculture, industrial production, and transportation.

Going regional

The resilient rebalancing of supply chains toward Asia-Pacific addresses only part of the need to focus more regionally. As we have argued in Asia Pacific’s Time, local companies need to join multinationals in pursuing growth closer to home, and build on the advantage they have as they either compete or partner with global players.

Family businesses and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in particular have an urgent need to do so. These businesses have historically focused on their home markets for growth, or on Europe and the United States. But now they face profitability pressures at a time when the pandemic has weakened consumption in the U.S. and Europe.

Fortunately, there is a supportive policy backdrop for this ambition. After a decade of negotiations, 15 Asia-Pacific nations signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November 2020. The RCEP reduces trade barriers between economies covering one-third of the world’s population and economic output, and marks a significant step forward in economic integration by replacing a latticework of preexisting bilateral trade deals.

And, speaking a month later, Masatsugu Asakawa, president of the Asian Development Bank, said there was recognition that Asia’s economic future depends on a new form of globalization in which deeper regionalization and integration have greater emphasis. “While some worry that globalization will retreat after the pandemic due to travel bans and trade restrictions, I believe that globalization will return, but it will take a different shape,” he said, listing five priority areas intended to equip the region to “rebuild smartly and return to a path of growth and prosperity.” At the top of that list was “deeper, wider, and more open regional cooperation and integration.”

Services to the fore

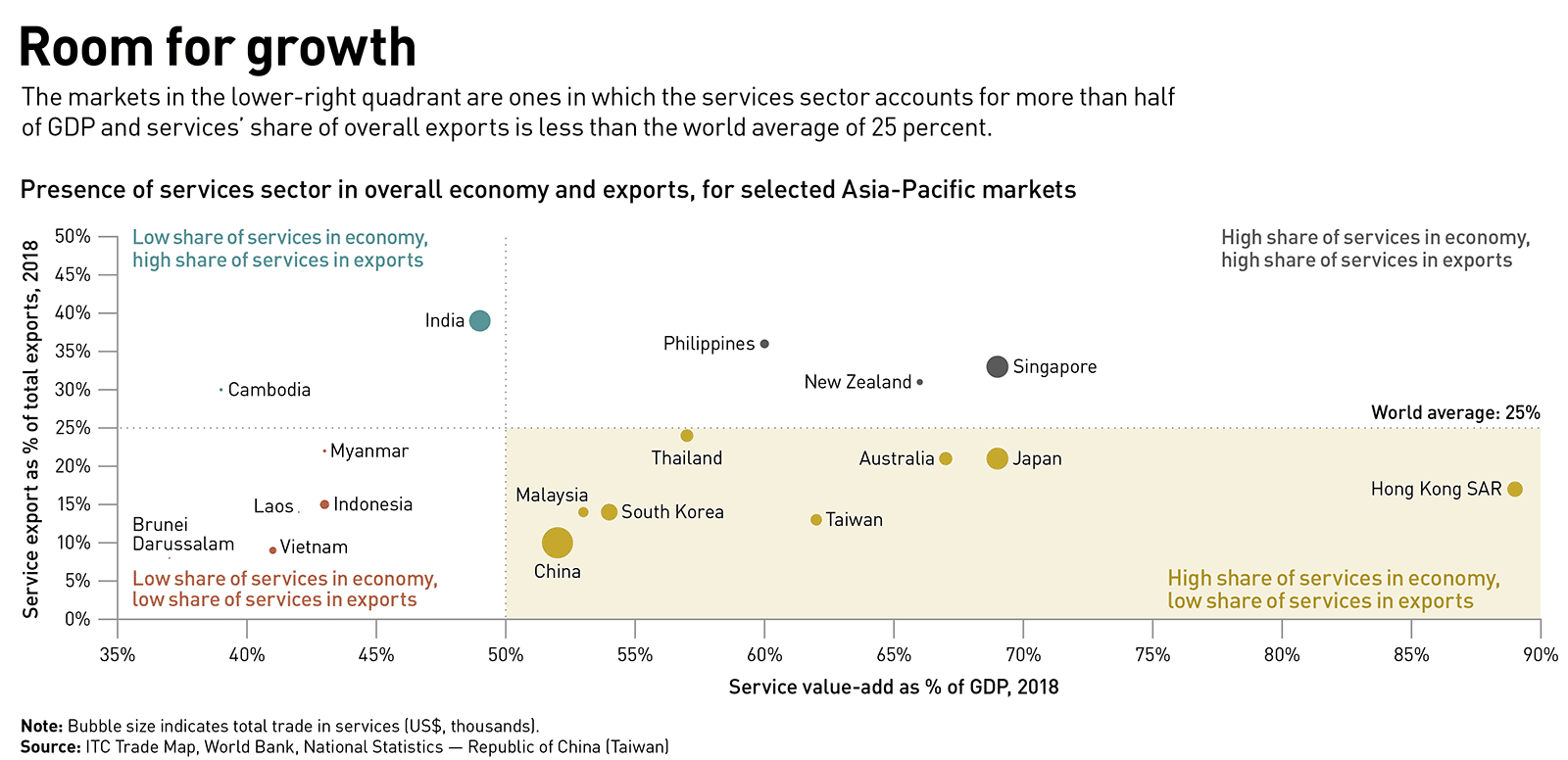

The services sector shows significant potential when it comes to how regionalization could play out on the ground. On average, services represented only 18 percent of Asia-Pacific’s exports in 2018. That’s significantly below the global figure of 25 percent, according to the International Trade Center. Although bridging this gap should be the short-term priority, Asia-Pacific has the potential to boost its services trade even further (see chart below). Globally, services trade will increase to beyond 30 percent of overall trade by 2040, according to the World Trade Organization, as a result of greater digitization and a reduction in policy barriers. Asia-Pacific could make great progress on improving its relatively low 18 percent share by focusing more on services exports.

Individual markets across Asia-Pacific also have complementary strengths in different services categories, pointing to opportunities for regional collaboration. For example, China, South Korea, and Japan all have the ability to export their expertise in construction services to the rest of the region, and India and Singapore could emerge as regional providers of information and communications technology (ICT) and professional services.

China, South Korea, and Japan all have the ability to export their expertise in construction services to the rest of the region, and India and Singapore could emerge as regional providers of information and communications technology (ICT) and professional services.

Countries with aging populations, such as Singapore, Thailand, South Korea, Japan, New Zealand, Australia, and China, are seeing higher demand for healthcare, insurance, and real-estate services, while demand for education, entertainment, transport, and travel is expected to remain strong in markets with younger populations such as India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Digitization, which has been accelerated by COVID-19, has further reduced the need for physical proximity to deliver these services, creating more opportunities for the remote delivery of services including education, entertainment, healthcare, and professional services.

Although the potential is immense and the intra-Asia-Pacific services market is developing organically, governments need to create a policy environment that fosters and safeguards cross-border transactions. Singapore has taken the lead by recently initiating a push on digitization of trade, including the use of digital technology by banks in trade finance, and the provision of other services through mobile apps and other platforms. It has forged “digital economy agreements” with Australia, New Zealand, and Chile, and a fourth is being negotiated with South Korea. These agreements aim to align digital rules and standards while facilitating interoperability among digital systems and, importantly, supporting cross-border data flows. This initiative holds out the prospect of providing practical help for private-sector businesses seeking to tap into the digital services trade.

Final warning

Despite the challenges it faces, Asia-Pacific remains the key driver of global economic activity. But the inescapable conclusion is that its success is by no means guaranteed. With the world pivoting away from globalization, more concerted intra-regional collaboration across Asia-Pacific is critical to ensure that the region lives up to its full potential. Guided by a common purpose and enabled by technology, the region could achieve much more.

The pandemic has delivered a devastating blow to societies and economies in the region, but the recovery period presents an opportunity for some tough decisions to be made. In fact, COVID-19 was a final warning to stakeholders in Asia-Pacific to rebalance now, with a sense of common purpose. That purpose is the reinvention of the engines of growth for years to come.

Author profiles:

- Raymund Chao is the chairman of PwC Asia Pacific and China. He is a partner with PwC China.

- Christopher Kelkar is global alignment leader and Asia-Pacific vice chairman and chief operating officer at PwC. Based in Hong Kong, he is a partner with PwC US.

- David Wijeratne is a partner with PwC Singapore. He leads PwC’s growth markets practice, a global team supporting companies as they expand internationally and realign existing supply chain and manufacturing footprints.