How organizations can design for agility and embrace uncertainty

Clarins Group’s organizational experiment during the pandemic shows how a large company adapts and becomes more flexible when it matters most.

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of strategy+business.

Before the pandemic, global cosmetics giant Clarins Group was making headway in its digital transformation. A family-owned business founded in France in 1954, with annual sales estimated at US$1.5 billion to $2 billion, the company had launched its own e-commerce sites and invested massively in a new customer relationship management (CRM) system. But it also had rigidities to tackle: Clarins’s approach to customer relationships was heavily reliant on intermediaries such as retailers and department stores worldwide. It was also slow to invest in digital marketing — in an industry in which startups and new brands innovating on that front were popping up everywhere.

Fast-forward to the outset of the COVID-19 crisis, when Clarins Group’s senior management realized it had to ramp up the company’s modernization efforts. In a highly experimental move, the company rolled out an organizational initiative focused on flexibility. With no time for messy restructuring, leadership formed three types of virtual, cross-functional teams it called squads (using agile terminology) that would work in parallel and with the support of the mainstream organization. It was a decision that would prove vital to the company’s ability to respond rapidly to unprecedented market shifts.

Clarins’s experience illustrates a need of which many businesses are all too aware: They have to accelerate the transition to organizational designs that enable flexibility and adaptation. Of course, amid a crisis, the most pressing challenges are often cash preservation and survival — which is not the ideal environment for experimentation, and is even less ideal for a sudden implementation of agile methods. In short, the pandemic firmly established the importance of agility, yet increased the roadblocks to embracing and embedding it within the organization.

Responding to uncertainty

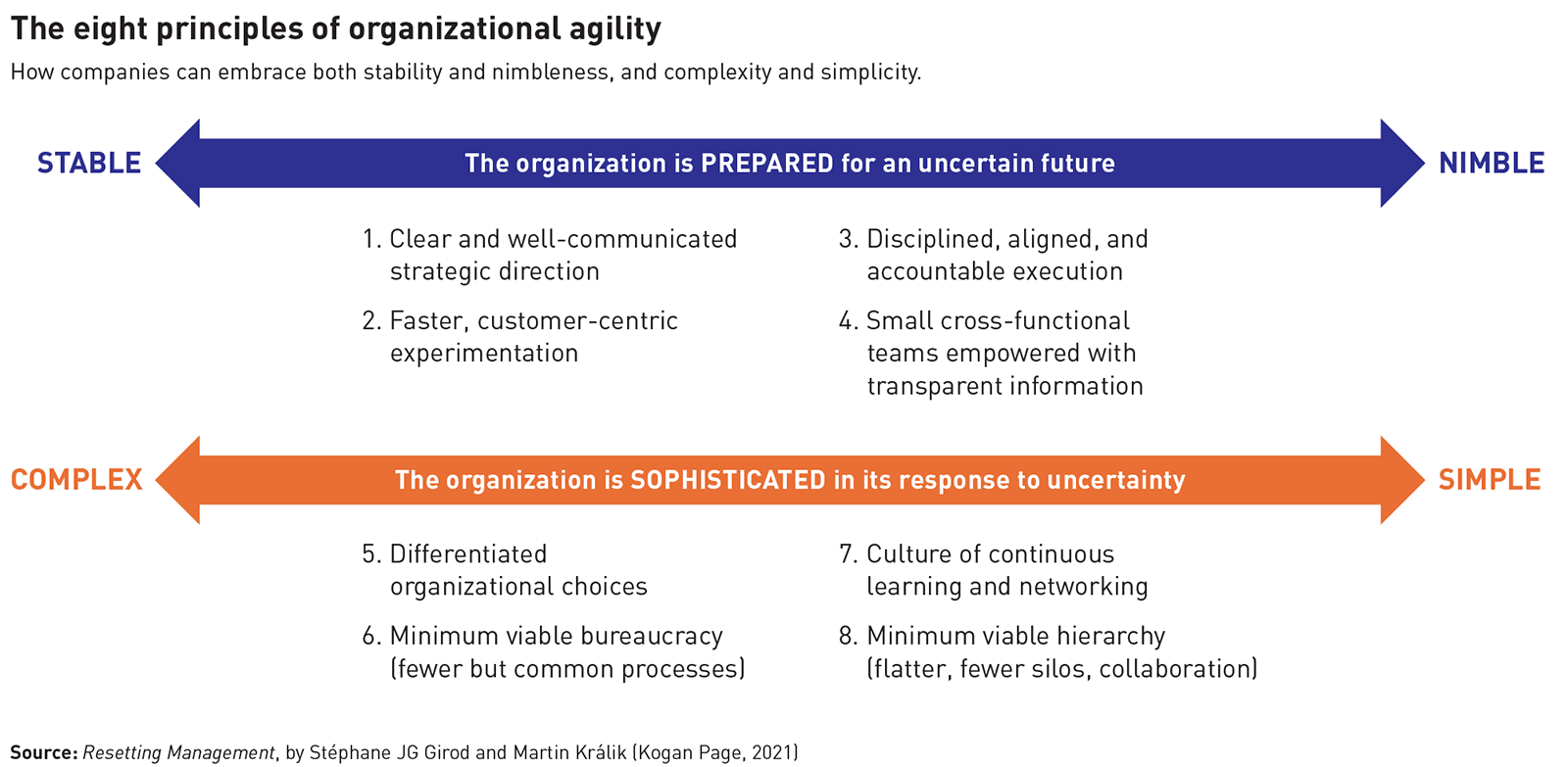

To better understand these challenges, in May 2020 we surveyed 550 executives in a variety of industries about their perception of agility. We found that although 64 percent of respondents reported that agility was a priority, 36 percent were confused about what agility really meant; they thought of it as a buzzword. We also found that 66 percent of respondents defined agility as “fast adaptation to uncertainty.” Yet our research shows that speed is only one dimension of organizational agility. Agility is the flexibility large companies achieve when their organization allows them to be simultaneously nimble and stable as well as simple and complex in response to high levels of uncertainty.

Our survey findings underscore the fact that shedding organizational rigidity is no easy task. The senior management team at Clarins Group faced this pressure in the spring of 2020. As the pandemic unfolded, it needed an organization that would allow for an unprecedented degree of improvisation and external focus. Yet management was also conscious that greater nimbleness would have to be achieved without sacrificing the internal stability that had long served the company well.

For large companies, the journey toward agility means building on the power of their scale while emulating startups’ nimbleness and simplicity.

Top executives also recognized that Clarins Group was a large incumbent with clear market positioning, a global brand reputation, and a very loyal consumer base. Not everything would change during and after the crisis. Some decisions, particularly the ones related to how the company would have to adapt to foundational changes in distribution, competition, and technology, would require time to make and embed. These leaders saw the need for speed (to become nimble), but also the need for caution and conservatism in uncertain times (to stay stable).

Clarins’s leaders also knew the company’s traditional geographic structure — which enabled it to be highly responsive locally in “normal” times — would inevitably create silos and inefficiencies. These silos could potentially derail urgent initiatives intended to accelerate digital programs, to make coordinated decisions to protect the brand, and to save money during the crisis. The company was pressured to create more cross-border commonalities and efficiencies. But at the same time, these initiatives had to be balanced with local relevance. Likewise, the drive to create savings and efficiencies (simplicity) had to be reconciled with the need to accept the right level of redundancies (complexity).

The Clarins experiment

To manage these competing priorities, Clarins’s leaders set up the company squads. The first squad was made up of the executive committee, including the CEO, the main functional heads, and the heads of the three business divisions, plus a few other non-C-suite executives. It focused on the question What now? to ensure business continuity during the crisis. This squad had five missions: protecting the health and safety of clients and employees, enabling staff to work remotely, keeping morale high among employees, preserving the top line, and retaining cash.

To boost efficiency, the first squad made instant decisions applicable worldwide, short-circuiting the internal bureaucracy and country managers’ prerogatives. As the squad met remotely, the team members soon realized they needed a shorter, more decisive, and more continuous approach to suit the new digital working format. They started to focus on shorter meetings structured around disseminating information, defining problems, having discussions, making decisions, and communicating on the spot to the organization to give employees a sense of direction and create a basic sense of stability.

The two other types of squads set up across the organization, designed to be small, cross-functional, and cross-hierarchical teams, were tasked with liaising with consumers, public authorities, retailers, distributors, suppliers, and other stakeholders to learn and continuously adapt Clarins’s responses accordingly. For quicker and more locally relevant decisions, every country where Clarins ran a division formed a second and third squad. Each of these squads included digital talent to enable its mission.

In the second type of squad, employees focused on the question What next? These squads had two roles. First, they were accountable for determining when and how operations could be resumed in their country after lockdown. These squads worked on issues such as defining the conditions for reopening physical stores, offices, and plants; rescheduling new product launches; and rebalancing investments between conventional and digital media. Second, they would update other squads in countries that were at different stages of the pandemic. For example, lessons learned in Europe could be transferred to the Americas.

The third type of squad focused on the question What if? and prepared for various contingencies — both offensive and defensive — when there were strong unknowns. Again, each squad had to determine which contingencies would materialize in its country and to share its insights with the other squads globally. For example, what if the country did not reopen within three weeks? What if customers needed to wear masks in stores: Would it reassure them or put them off altogether? What if 30 percent of intermediaries disappeared? These squads were also scanning for the more fundamental changes in consumer behaviors, competition, and technology that would affect Clarins’s strategy once the health crisis receded.

For instance, in the United Arab Emirates, the local What if? squad decided at the outset of lockdown to move all the inventory from the now-closed stores to a temporary warehouse. In only three days, using the CRM system put in place pre-crisis, they were able to switch from store pickup to home delivery to avert a sales free fall. The squad also created an online appointment option so that boutique sales staff could provide regular personalized beauty advice to consumers via their mobile phones.

In France, the What if? squad came up with a digital-to-human solution to keep consumers engaged. Clarins France unveiled an appointment system on its website to allow consumers to book consultations with Clarins beauty advisors via Apple FaceTime or Microsoft Teams. By using these conversations to recommend relevant products to consumers, the advisors kept selling products despite constraints on in-person interactions.

Although it is perhaps too early to declare victory, the Clarins experiment is an encouraging sign that this type of organizational innovation, up to this point largely experimental, could bear lasting fruit. Moreover, the company has been able to strengthen its direct relationships with consumers and to protect some of its revenues by mobilizing the collective power of employees at all levels of the organization. Christian Laurent, president of Clarins Group’s travel retail and export worldwide division, told us, “Many companies ignore uncertainty or remain paralyzed by it. Rolling out the three squads allowed Clarins to place the external uncertainty at the core of our organization.”

Agility lessons learned

In our research, we found that large, established businesses tend to be rigid because they are usually too stable and complex to deal with the uncertainty and pace of change surrounding them. The journey toward agility means building on the power of their scale while emulating startups’ nimbleness and simplicity. But many executives in search of agility will default to popular agile methodologies such as scrum. Although these may be useful, they cannot be assimilated quickly in a crisis — companies can and should be agile, without necessarily “doing” agile.

Although it created the three types of squads, Clarins Group did not adopt a specific agile method; instead, it designed its organization around the eight fundamental principles of agility (see chart). To strengthen its nimbleness, it designed an organization that empowered employees in small cross-functional teams (the What if? and What next? squads) to experiment fast by learning from customers and from industry trends. At the same time, the What now? squad was laying a foundation for stability.

Clarins also simplified how the company worked while allowing for the right level of internal complexity. Its move to bypass the traditional bureaucracy and country silos was designed to streamline the organization by creating commonly enforced decisions. But company leaders also had to respect the complexity of its global footprint across advanced and emerging markets by differentiating some decisions at the country level. Indeed, every business should design its approach in ways that suit its strategy, industry, and overall performance. The level of uncertainty and speed of change might differ from business to business or even within a company.

Leaders also need to take a holistic approach. Yet in our research, we found that many companies do not seek to shed their rigidities in a sufficiently holistic fashion. For example, when companies introduce scrum or lean startup, they focus on the ceremonies and processes, but they often forget to realign incentives, leadership style, rewards, and so on. Contrast this with Clarins Group. Although the company didn’t embark on a formal restructuring, through its squad experiment it aimed to align key elements of its organizational design so they would reinforce one another: developing global processes, increasing its use of digital communication and collaboration tools, introducing new incentives and metrics, and focusing on leadership buy-in.

Finally, Clarins Group executives are aware that once a certain degree of normality returns, the company might fall back on old habits — and they are mitigating this risk in several ways. For example, they have treated their squad experiment as a pilot from which they and the whole organization will learn, and they are planning a company-wide review after the pandemic recedes to assess how the organization should continue to evolve.

Another mitigation tactic is related to leadership style. To promote nimbleness, the leadership team has been working on how to create what we call a secure base for employees to experiment — making failure an acceptable and indeed critical part of the path to success — and leaders have been supporting middle managers to build this base, as well. The learning network put in place at Clarins enabled employees to share what worked well (and what didn’t). By providing a clear sense of direction and ensuring rigorous accountability, management also created a sense of reassurance and trust. They knew they needed to model the change for the transformation to take hold.

We’re often told by senior leaders that their greatest fear when it comes to agility is chaos. Although agility does require leaders to pursue bold experiments, the goal is to gain flexibility while retaining stability. Leaders do this by understanding what agility is and building a comprehensive approach based on its core principles, rather than defaulting to agile methods. It’s not a matter of losing control, but rather creating an environment in which companies can change with the times and respond to uncertainty in a way that balances what they are with what they want to be.

Author profiles:

- Stéphane JG Girod is a professor of strategy and organizational innovation at the Institute for Management Development (IMD) in Lausanne, Switzerland.

- Martin Králik is an IMD external research associate.

- This article is adapted from Resetting Management by Stéphane Girod and Martin Králik, © 2021. Reproduced with permission from Kogan Page Ltd.