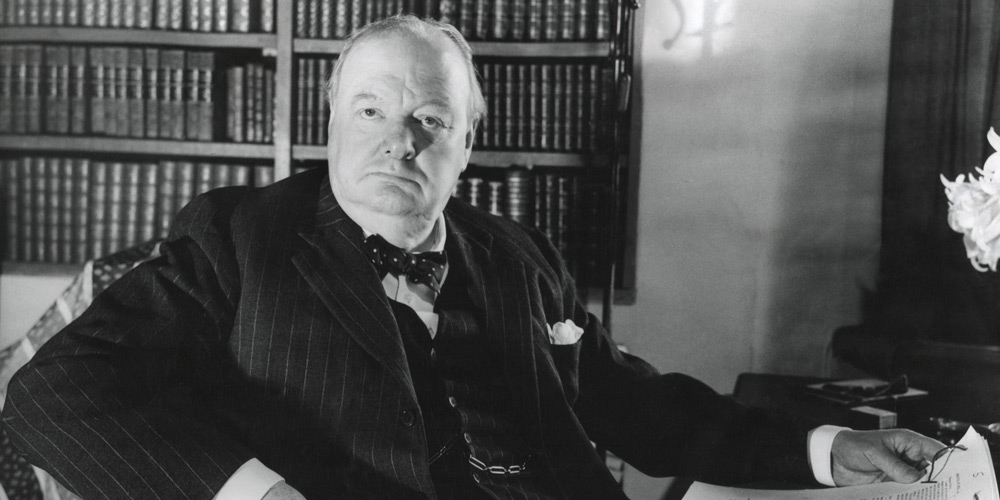

Not Winston Churchill’s finest financial hours

The legendary leader’s political successes were continually undermined by his financial and business failures.

In the wee hours of September 1, 1939, as German tanks rolled into Poland — triggering a war nearly everyone knew was coming — Winston Churchill was dictating new material for his latest book.

Not yet prime minister or even a cabinet member, Churchill worked frantically to finish his History of the English Speaking Peoples because his finances were, as usual, a shambles. Winston Churchill and his wife, Clementine, were beset by piles of bills, overdrafts at the bank, and overdue taxes, mostly the result of their reckless overspending. If he didn’t finish his manuscript before the declaration of war, which would in fact lead him back into government, he would forfeit the £15,000 still due from the publisher and have to pay back the £5,000 he had already received — and spent.

That was a lot more than you might think — £15,000 in 1939 comes out to roughly US$1.4 million in today’s money.

The name of Winston Churchill, of course, is virtually synonymous with highly effective leadership — a record that resonates with both politicians and corporate chieftains. Despite his record of policy blunders and retrograde views, Britain in its darkest hour turned to this eloquent aristocrat, steeped in military action and public life, for salvation in the face of mortal peril.

A widely praised recent biography of Churchill, Andrew Roberts’s Walking with Destiny, makes clear that there is plenty to be learned from his successes as well as his failures. But a slightly earlier book about Churchill, No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money, by David Lough, offers some lessons of special interest to today’s high-achieving leaders in the realms of public and private enterprise.

Although Churchill was born into Britain’s upper crust at a time of massive inequality, his family wasn’t particularly wealthy by the standards of its social class. His father, Lord Randolph Churchill, wasn’t the oldest son, which left him with a relatively modest inheritance, and young Winston’s American socialite mother (born Jennie Jerome) was a hopeless spendthrift. Churchill showed unmistakable signs of familial profligacy as a schoolboy, when his mother complained of his frequent requests for money: “You do get through it in the most rapid manner.” He even borrowed from his beloved nanny, who called him “awfully extravagant” for spending more in a week than some families “of six or seven people have to live upon.” Most tellingly, she noticed that “the more you have the more you want to spend.”

That was to be the pattern of Churchill’s life, as Lough, a longtime private banker, makes clear in his remarkable financial biography. The book should be required reading for anyone who aspires to business leadership, for it amounts to a catalog of the financial pitfalls into which the highly confident and amply compensated can so easily fall. Proceeding chronologically, and even providing exchange rates and inflation multipliers for each chapter, Lough has performed a miracle of forensic accounting to unravel his subject’s tangled finances. It makes absorbing reading.

Perhaps the most important lesson Lough offers here is that mismanaging your personal finances can lead to moral and professional compromises. Repeatedly, Churchill relied on rich admirers to rescue him from debt and even bankruptcy. He depended on various newspaper publishers for the high writing fees he lived on for much of his adult life. And he engaged in contortions to avoid taxes that other Britons had to pay. As chancellor of the exchequer, he demanded rulings on his own taxes from Inland Revenue officials when that agency was under his purview.

“Clearly some of his actions or omissions would not survive scrutiny by the standards of transparency expected of today’s politicians,” Lough writes. To wit: “While responsible for South Africa’s government as colonial secretary after the First World War, he held on to his South African mining shareholdings; and within a year of losing office in 1922 he earned a substantial fee from two oil companies in return for lobbying his former ministerial colleagues. After the Second World War, while leader of the Opposition and then prime minister, he accepted interest-free loans from a national newspaper, The Daily Telegraph.”

Churchill used his social and political position, moreover, to get cheap credit and cow those he owed, including his bank. In 1914, his debt to his wine provider reached $50,000 in today’s money, and at one point he hadn’t paid his cigar provider in five years. Despite all this earning and spending, the Churchills evidently gave little thought (or money) to charity.

In 1914, Churchill’s debt to his wine provider reached $50,000 in today’s money, and at one point he hadn’t paid his cigar provider in five years.

Churchill’s financial troubles also warn us loudly to beware of hubris. His courage and self-confidence were boundless, but when it came to money, Churchill was madly overconfident, behaving as if, in this arena along with so many others, he was destiny’s child. He earned a fortune during his lifetime, but frittered it away through overspending, reckless investing, and near-compulsive gambling.

“I have never encountered risk-taking on Churchill’s scale during my career of advising people about their finances, including such natural risk-takers as entrepreneurs and politicians,” Lough writes, adding: “He gambled or traded shares and currencies with such intensity that he appeared to be on a ‘high’ — devoid of inhibition, full of self-confidence and energy.”

The problem wasn’t earning; it was spending. For the tax year that ended in April 1932, Churchill took home more than £15,000 (equivalent to about $1.5 million in 2019 dollars), placing him among the country’s top 10,000 earners. But his spending and losses reached £30,000, or something approaching $3 million today.

Churchill’s experience illustrates how difficult modern taxation makes it to earn your way out of a hole. Postwar Britain’s top marginal rate of 97.5 percent forced him to strategically “retire” from his lucrative career as an author more than once, and necessitated Herculean efforts at tax avoidance. Today’s rates are much lower, but in most of the world’s advanced economies, income taxes still bite hard, to say nothing of sales taxes, estate taxes, and property taxes.

Speaking of property, a major factor in Winston and Clementine’s financial woes was real estate. The Churchills acquired Chartwell, their country house, in 1922, after receiving an inheritance that seemed sure to abolish their financial troubles for life. Unfortunately, the house proved a classic money pit, with renovations costing several times the original estimate, architect and contractors pointing fingers at one another for overruns and leaks, and overinvestment far above what any market valuation would support.

Chartwell was a bad investment. But so were most of the others Churchill made. He bought and sold based on tips from friends and veered from Colorado mining stakes to Argentinian railways. He also traded on the thinnest of margins, with disastrous consequences in the crash of 1929.

Lough’s book demonstrates vividly how distracting risky investments and financial turmoil can be. Even during the war, the Churchills were struggling to keep their heads above water: “Churchill’s salary as prime minister might have doubled to £10,000, but nine-tenths of it disappeared in tax payments; the remainder did not even meet the interest payments on his loans.” As a result, on one occasion the prime minister spent time with his tax advisor instead of attending a House of Commons debate on the conduct of the war.

Churchill repeatedly fell victim to wishful thinking, especially to overly optimistic mental accounting — something capable executives should beware of in themselves. Again and again, he grossly underestimated spending, overestimated how much was likely to come in, and counted on money not in hand. For 1939, Churchill projected income of £22,000 against anticipated spending of just £13,000. “The eventual outcome of 1939 was to be almost the reverse of Churchill’s estimates,” Lough reports. “He finished with receipts of £13,000, while he spent more than £20,000.” The shortfall today would be about $500,000.

Finally, and most obviously from Churchill’s story, personal indebtedness can be the devil. Year after year, Churchill’s debts grew. Often when he had a windfall, he directed it toward speculative investments — or just increased his spending — rather than paying the debt down.

Of course, money isn’t everything. Churchill is remembered not as a spendthrift but as one of history’s greatest leaders for rallying his people against Hitler’s onslaught and managing the ordeal of total war. The accounting of a historical figure’s life is not a simple matter of accounting, after all. But Churchill’s financial woes should stand as a cautionary tale for people who lead in any capacity.