Tech is no cure-all where emotions run high

Autonomous buses seem like a natural solution to a school bus driver shortage, but parents would certainly disagree.

Nationwide, as the Wall Street Journal reports, there is a shortage of school bus drivers. In the past decade in Wake County, N.C, the number of schoolchildren has risen 25 percent while the number of drivers has fallen 18 percent. And it’s not just in North Carolina. “Roughly 90 percent of 231 school districts in a School Bus Fleet magazine survey last fall said they were short on drivers,” the Journal noted.

This state of affairs is predictable. The U.S. has enjoyed 77 straight months of payroll job growth, unemployment is at 4.7 percent, and there were 5.6 million job openings at the end of January. If you want to fill an open position in today’s economy, you have to convince someone to leave a job they already have or make it really worth someone’s while to come off the sidelines. But the starting pay that Wake County is offering for this job, which involves getting up very early in the morning, is…US$12.55 an hour. Annualized, assuming a driver works 40 hours a week for 52 weeks, that’s $26,104. Which isn’t much. Besides, many bus driving jobs are part-time, which means the potential earnings are even less.

When you’re facing a labor shortage, there’s one obvious choice: Raise wages. And school bus fleet operators are doing that. “More than half of the districts raised hourly pay this academic year to an average of $15.51, 31 cents higher than the previous year, according to the survey,” the Journal reported. That’s an increase of…about two percent. Which, also, isn’t that much.

Given the conditions in today’s labor market, it’s a battle to hire people — at every skill and salary level. But bus fleets aren’t coming properly armed. Something tells me that if driving a bus started at $20 an hour in Wake County, rather than $12.55, there would be plenty of applicants.

A second option for organizations aiming to hire in a tight labor market is to redesign the job to make it more appealing and compelling at the wages you can offer. You can add benefits or training, or offer snacks and amenities. The Journal notes that some bus fleet operators are pursuing this route by “creating combined bus driver–custodian and bus driver–cafeteria jobs that are full-time with benefits.”

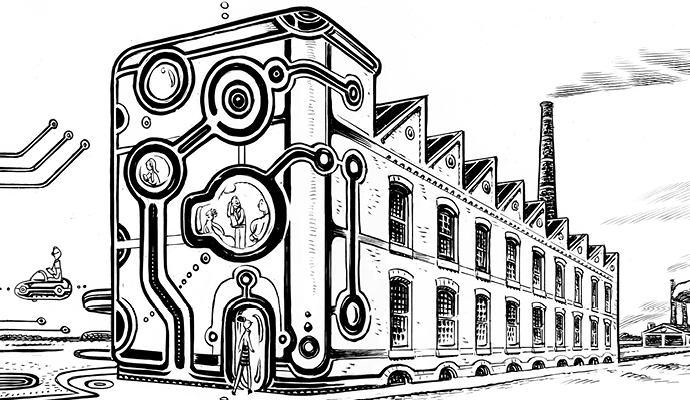

There is, of course, a third solution when wages or redesigned jobs won’t do the trick: Invest in automation. And, if the analysts and evangelists are to be believed, we are at the beginning of a golden age for the development of automated driving. Technology that assists drivers and allows cars to drive themselves has essentially arrived. And although the applications for consumers get most of the ink, it is the use of driverless cars in business that is likely to have the more far-reaching impact. After all, replacing a human driver with a robotic one offers organizations the ability to get permanent savings on labor, thus creating a significant structural change to business models. A self-driving truck has already delivered beer. A British company has developed Olli, a self-driving shuttle. London is testing a self-driving bus.

School buses would seem to be a natural fit for going autonomous. The operators of self-driving school buses wouldn’t have a problem getting up before dawn, wouldn’t be put out by working a few hours in the early morning and a few more in the afternoon, with a big gap in the middle of the day. They wouldn’t get annoyed by a busload of screaming kids.

And yet, one could also imagine that school buses would provide an extremely difficult test case for automation. When parents drop their kids off, they are putting their most precious possessions in the hands of the individual behind the wheel. And their highest concern is the safety of their children. In theory, we know, and are beginning to understand, that robot drivers should be safer than humans at some point in the near future. But we don’t fully have the trust in them to do it. Imagine that a school district announced it was conducting a pilot whereby two of the eight bus routes would start using self-driving buses. My bet is that the parents on those two bus lines would revolt. And many districts would likely conclude that it isn’t worth the risk to be a first mover. The safety of driverless vehicles would have to be proven in other areas — shuttle buses at airports, taxis, corporate fleets — before it would get serious consideration in schools.

School buses would seem to be a natural fit for going autonomous.

Just because a technology can do something doesn’t mean it will. As Vinnie Mirchandani noted in these pages, society often erects roadblocks and circuit breakers that slow the rapid rollout of new technologies. Driverless cars — and especially driverless school buses — won’t be any different. People are generally pretty adept and open to embracing technological change. But when it comes to technological changes that have the capacity to affect the health and well-being of their children, they tend to move a little slower.

Technology can bail out a lot of businesses from the challenges they face. It won’t do much to help the bus fleet operators who are facing chronic labor shortages until other industries prove the technology is unwaveringly safe.