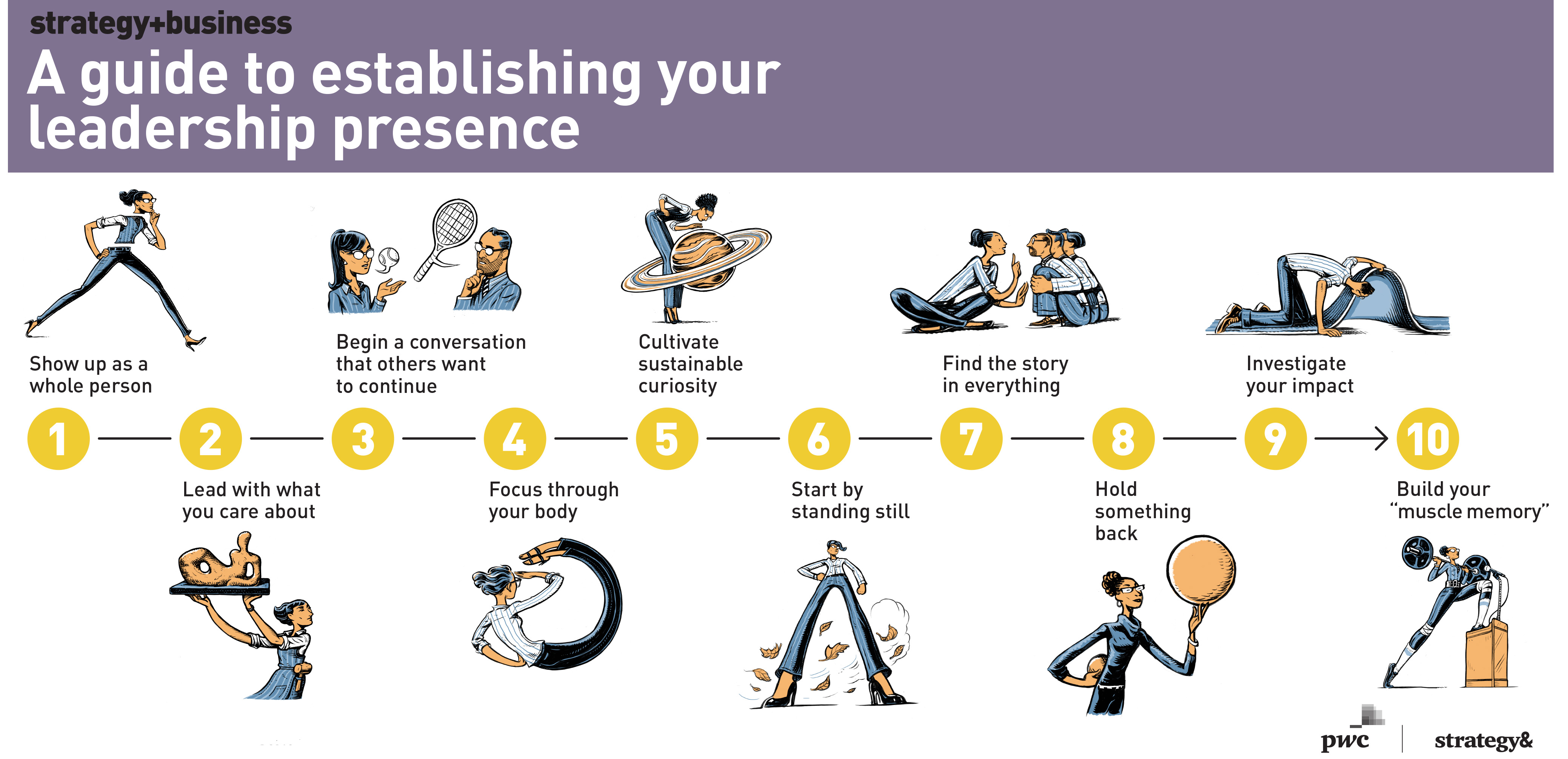

10 principles for leadership presence

Build muscle memory to support conviction, commitment, and resilience for yourself and your organization. See also “A guide to establishing your leadership presence.”

A version of this article appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of strategy+business.

Think back to the last conference you attended. How many presentations do you remember? Probably not too many. As a leader or aspiring leader at any level, one of the biggest challenges you face is to inspire and motivate other people so that they can take the right actions on behalf of themselves and the group — that is, to have impact. That’s why you want to be a leader with a strong presence not just at conferences, but in every interaction. And if you are such a leader, then every aspect of your presence — including your physical self, your intellect, your voice, and your emotions — is intimately bound up with your message.

Many people in positions of authority struggle with their leadership presence. They adopt the kind of persona that they assume a leader is supposed to have: a TED Talk cadence, authoritative body language, studied informality, and (when speaking publicly) a package of carefully curated slides. This makes these people look and sound like everybody else, because the fashions in leadership presence rapidly become clichés. Most of the time, behaviors like these are immediately recognized as a performance. If you try to adopt them, people will know you aren’t authentic, and they will assume your message isn’t, either.

One alternative is to borrow the methods and principles of the performing arts and integrate them into your approach to leadership. You can gain trust and influence by expressing your true purpose and commitment to others in a genuine way. Many people misunderstand the performing arts and associate them with artifice. In fact, a strong performance, even in a fictional drama, depends on authenticity. The craft involves looking deep within yourself and portraying outwardly, in the moment, the core of what you know to be true. As acting teacher Sanford Meisner said: “You can mask [emotion], but you can’t hide it.”

At the same time, being an authentic leader doesn’t mean just “winging it” or saying whatever you feel. It takes time, experience, and practice to learn to transform your impulses into insights — and to articulate them and act on them in a way that fulfills your purpose and builds the relationships you need.

The value of this type of leadership — the ability to communicate what needs to be said in a way that inspires people to join you — has risen sharply in recent years. Trust is increasingly considered a key competitive advantage. The more you rely on scripted talking points and other rote forms of communication, the further away you will feel from your message, and the less likely you are to be an influential leader. But when you are comfortable in your own skin and capable of projecting a sincere and valuable message, people will tend to give you and your organization their trust. Here are 10 principles to help you establish and sustain your own unique authentic leadership presence.

1. Show up as a whole person

You may have grown up thinking of your intellect, emotions, and body as separate. You may have neglected some aspects of yourself; most people have, simply out of habit. But when you speak, others perceive you as a whole. People don’t engage only with the literal meaning of what you say and the images you show. They are continually evaluating your integrity and veracity as they take in your posture, tone of voice, and mood. All of these are mixed together in the listener’s mind as a single impression of you and your message.

You may have grown up thinking of your intellect, emotions, and body as separate. But when you speak, others perceive you as a whole.

How, then, do you develop the skill to communicate as a whole person? Concepts such as emotional intelligence (EI) have helped businesspeople recognize their biases and avoid giving in to their impulses. But it’s not enough to manage your feelings, as EI teaches. You also have to recognize the feedback loops among your logic, your feelings, and your physical movement, and to work with those elements together to improve your overall impact.

As an example of how these elements fit together, consider the performance appraisals in your company. Typically, subordinates are ranked according to strict universal criteria, which are designed to seem objective — a matter of cold logic and intellect. Inevitably, however, there will be review conversations with two bodies in a room. The outcome and the level of trust present will generate emotional and physical responses; people will feel passionate, or stressed, or they will sense that something is right or wrong. As appraisal and other feedback encounters take place over the years, these gut feelings accumulate. They affect the way people fill out the forms and ultimately may even affect the phrasing of the criteria. All of these interactions, among mind, body, and emotion, influence one another.

The same is true of every other decision you make as a leader. Just recognizing the connections among your emotions, reasoning, and actions can lead to more honesty and authenticity. Doing so may take a different kind of introspection than you’re used to. You can work with a coach to help the process. Your goal is to become more aware of all the elements of your persona — your physical body, your relationship with your listeners, and your relationship to what you want to accomplish — and to practice what it feels like to integrate them.

2. Lead with what you care about

You’re at a panel discussion about blockchain. The speakers include high-ranking officers of Fortune 100 companies. One by one, they introduce themselves, giving their name and title. Every talk is about the productivity that will come as the new electronic ledgers eliminate “intermediaries” — by which they mean the managers who currently oversee the verification of transactions. By the fourth such presentation, you can see the audience’s attention wandering.

Then one speaker makes the room come alive. He looks at the audience and says, “Like my colleagues, I too am experimenting with this technology. My company also sees it as a way to eliminate intermediaries.” Then he stops himself. “Actually,” he asks, “What’s wrong with intermediaries? A better word is guardian. I am proud to be a human guardian of the blockchain’s credibility. It’s people like us, in fact, who will keep advanced technologies honest. We can’t delegate that entirely to an algorithm.”

You, and all the others in the room, are playing close attention now, because the speaker has focused the conversation, right from the beginning, on something he cares about. It’s not just his job at stake (although he admits that’s part of it). The main issues are the unintended consequences of technological change, and the challenges involved in dealing with those consequences.

The most effective communicators are those who speak about what is important to them, in the context of what they are trying to accomplish and what their listeners care about. Start there. Figure out what you care about and why. Think about its connection to your purpose and your listeners. Commit to it wholeheartedly. Only then can you make clear to others your conviction, your willingness to invest your time and other resources, and your aspiration for others to understand it as you do. Your capacity for expressing commitment will continue to improve with practice.

3. Begin a conversation that others want to continue

Real leadership is relational. It begets genuine engagement and trust. Use every opportunity to engage with people rather than broadcasting to rooms or groups. With this orientation, you will no longer perceive yourself as a lone leader, separate from others, and neither will anybody else.

One executive who learned how to do this was the CEO of a major international organization — and also the only woman and non-family member on its board. Each year, she spelled out her objectives and proposed her budget in an annual presentation that took months to prepare. During the few weeks leading up to the meeting, she barely slept. Then she covered the material in the sequence the board had asked for, with a painstaking account of her preparations and conclusions.

Despite all that work, and the high quality of her material, she never felt like she was being heard. At first, she thought her gender and outsider status were the reasons. Then she realized that her preoccupation with those differences had been driving her to blend in and pay less attention to her own priorities.

She began to think about the other board members as people. What did they care about most? (It wasn’t money.) What did they usually talk about? What would they pay attention to? She dedicated her time before the board’s next meeting to answering these questions. Then, instead of presenting information, she opened with a conversation. She named just a few key decisions that had to be made, and invited the group to discuss them. She made it clear that she was prepared, on every point, with the background information they needed but that she would bring it forward only in the context of questions as they came up.

The board not only paid attention but commended her on her excellent work, and the positive response gave her renewed confidence as a leader. In the years that followed, her leadership prowess became a subject of widespread comment in her industry. It all began at that meeting.

There are many ways to transform a performance into a conversation. In your speech, be concise. If you’re given seven minutes, take three. No one will say, “You didn’t talk long enough.” Use the points you make to invite a response. Then pay attention to the conversation that follows. Even those who don’t speak will feel more comfortable and more receptive to a productive relationship with you, because it’s now clear that you are open to dialogue.

4. Focus through your body

It’s hard to overstate how much your physical self is involved in the way you are perceived as a leader. How you move affects the way you feel, and how you feel affects the way you move, and it all changes the way you think and communicate. If you doubt this, stand up and raise your arms in a wide V over your head, and push your chin forward as if you’re crossing the finish line of a race. Social psychologist Amy Cuddy has noted that primates often adopt this position at times of triumph. Even at less dramatic times, it tends to generate a feeling of confidence. Some of the business leaders I know privately spend a few minutes per day in this position precisely for that reason.

If you are comfortable with your body in general, you have an advantage over those who are not. You can command the room before saying a word. You don’t have to be an athlete, but even a moderate level of physical vitality energizes and supports your conviction and authority. Your listeners interpret it as a form of authenticity, and are more likely to respond with engagement and trust.

A positive relationship with your body is not achieved overnight. It involves refining your breathing style, gestures, and movement so that you are in sync with yourself: physically, emotionally, and intellectually. This can be done in many ways, for example, through coaching sessions or movement classes in a variety of disciplines. Breath work is one particularly useful thing to learn — to alleviate stress, regulate your mood, and more.

Many theater exercises are designed to develop body awareness. Try walking around the room with different postures, imagining that a string, attached to a different body part each time, is drawing you forward. Pay attention to your response; what kind of person feels this way? Does leading with your nose transform you into a busybody? Does leading with your chest lend you authority, or your hands make you feel expansive and engaged? Try your knees, your chin, or the top of your head. The effect varies from person to person, so don't assume there is a universal response. Instead, draw your own conclusions. How does each one of these walks make you feel?

When you build physical awareness, the body leads and the intellect follows. Reading descriptions of the process can take you only so far. Learning comes from doing. And the process never ends; even people who are very familiar with their bodies can learn to better channel that familiarity in a way that reaches other people.

5. Cultivate sustainable curiosity

Because there is always too much to do and too little time, people in positions of authority try to avoid distractions and operate efficiently. This often translates into shutting themselves off from other people and their ideas. But leaders with a strong presence are open to the world. They cultivate sustainable curiosity: They are continually drawn to the unexpected and unfamiliar.

In some organizations, sustainable curiosity is considered a specialized talent, indulged in by only a few “creative” innovators. But curiosity is an inborn element of human nature, and those who are truly competitive have learned to tap into it. The ex-surfer who still goes down to the beach sometimes to see what might happen on the waves; the public speaker who lingers to take just one more question from the audience; the marketer who can’t resist reading social media comments; the technologist who follows journals outside his or her narrow field — they are all driven by the prospect of finding something unexpected. They may spend more time listening than talking, and yet they are often compelling leaders, because their interest is infectious; others are likely to join them in their explorations.

You can demonstrate sustainable curiosity — or the lack of it — in the ways you interact with people. Interrupting someone else, for example, sends a visceral signal that you are not interested in what they have to say. Most people respond by losing interest in your message. If you do interrupt, do so genuinely in service of the group and make the reason clear. (“We only have 15 minutes left, and I want to make sure others get to speak.”)

The chief technology officer of a large aviation company set up a rule for weekly meetings that brought curiosity to the forefront for all attendees. He decreed a time limit of five minutes for the whole session — unless attendees could convince him they deserved more time. To make their case, people had to read the room: figure out every person’s mood, how people were likely to respond, and whether each person would think a topic was important enough to add the time. This made everyone intensely curious about one another. After a few weeks, managers in this group found themselves buttonholing each other between meetings to ask what was going on with them and how they felt about it. The ideas presented in the weekly meetings became more robust, because they reflected the connections among what everyone was thinking.

If you believe you are not naturally curious, because of your lack of interest in some aspects of your job, one strategy is to remember experiences or activities that sparked your curiosity in the past, and what you loved about them. You might have been a runner, for instance, and loved the feeling of discovery when you reached the crest of a hill and saw the vista on the other side. Or you might have loved the thrill of being an investor and finding out that your instincts about a company were getting good results in your brokerage account. Once you identify what made you curious in that situation, find opportunities to apply the same attitude in your work. By deliberately reliving those memories, you can reinvigorate your curiosity, reclaiming all the intellectual and emotional resources that came to the fore then — and that will help you now.

6. Start by standing still

A CEO from one of the world’s largest media companies was having trouble giving talks. For the first 15 minutes, her audience sat stone-faced as she talked; then, gradually, they warmed up. Watching a video of herself, she noticed that she began speaking almost as soon as she arrived onstage, pacing back and forth before the group. Theoretically, there was nothing wrong with this movement. After all, didn’t Steve Jobs pace? Onstage, however, she lacked gravitas and authority.

The culprit was nerves. This CEO was so concerned about filling the stage that she lost track of what she wanted to say. She hired a coach, who told her to stand in one place, take a breath, count to five before beginning to speak, and command the room through her stillness. This sounded easy, but it took a surprising amount of practice to master. At first, the interval seemed like an eternity — she knew she had a limited time, a clock counting down in front of her, and so much to say. However, she noticed that after waiting for five counts and taking a deep breath, her voice sounded lower and there was an air of suspense in the room. By standing still, she created a structure for herself that attracted everyone’s attention. She no longer felt the need to pace, and she could focus more on getting her ideas across.

Many leaders feel exposed in front of an audience, especially when there is no lectern or table to stand or sit behind. By standing still at first, you invoke deeper, more deliberate breathing, which helps you gather your thoughts. After that start, whoever you are — cheerful, resolute, stern, optimistic, empathetic, expert, passionate, analytical, earnest, or any combination of those qualities — will come across more powerfully.

Stillness is important not just for its effect on you, but for the impression it leaves on others. Five seconds of standing still will come across as thoughtful attention. It’s no coincidence that people use the phrase “standing for something” to mean having conviction. After that beginning, your movement will seem more natural and effortless, because it is.

7. Find the story in everything

Although children are aware of their love of stories — both telling them and hearing them — many adults, particularly in business, forget that having a compelling narrative is a powerful tool. Stories create relationships between listeners and leaders through empathy with characters and connection with personal experience. They provide structure that makes your points seem inevitable. They show people what you mean to say, bringing the abstract and general down to earth and making it concrete, specific, and relevant.

Too often, business leaders ignore the stories they have to tell. Instead, they collect data and summarize it in list form, assuming that will substantiate their message. But no one has ever been persuaded by data alone; people are persuaded by the way they feel about the data. Without an explicit story that makes sense of it, the data is much less meaningful.

This is why PowerPoint-driven presentations often dilute the authority of a speaker. Listeners have a hard time splitting their attention between the data on the screen and the story told by the voice. You can be more effective with slides if they support, rather than repeat or distract from, your story.

There are many ways to find and articulate a compelling story. One good general way to start is by asking, “When did we begin to care about this?” Then, “What happened next?” Then, “What did it all lead to?” And then, “Why do we care about it now?” The answers can be building blocks for your narrative, sequenced perhaps in the order in which they happened.

Don’t worry about whether your story is literary, whether it has characters and conflict, or whether it follows the arc of a movie script. Simply pull together and sequence the elements that are meaningful to you and will be meaningful to your listeners. Even if they’re just about the progression of a financial projection, those elements mean something. Everything you say will be perceived as a story anyway, so take advantage of that. Give listeners your authentic view of how the elements fit together, of the chain of cause and effect as you see it, and of which elements are most important. Study stories that you love (including videos by speakers you admire) to see how they make an emotional connection.

When it comes to the wording, use frank, natural language — simple, clear words such as you might use around the dinner table with your family or friends. Jargon, including many of the words that leaders and managers typically use, will be perceived for what it is: a vehicle for protecting yourself by making the subject less personal. Even evocative jargon, such as “boiling the ocean,” makes it hard to achieve a shared understanding, because it reminds people of other times they have heard the phrase.

In the end, there is only one universal rule for storytelling: Everything you say should make people listen to the next thing you say. You can know if you have accomplished this by trying it out, being curious about the result, and iterating over time.

8. Hold something back

“People used to come to me when they needed to think outside the box,” said a sales executive. She was deeply upset. “However, I’ve recently been getting feedback like, ‘You have too much energy.’ ‘I can’t have you at a meeting.’ ‘You ask the wrong questions.’ ‘You bother everybody.’ What am I doing wrong?”

For several years, she had tried to play the role of an authentic leader at her job. She had great curiosity, compelling body language, and terrific relationship-building skills. But something was clearly off. I asked her to say as little as possible during the next few meetings, and to instead pay attention to where other people were paying attention, and how they were responding to one another’s behavior.

When we met next, she had identified the problem. She had been saying too much, substituting her own expertise for the progress of the group’s learning. She needed to hold back and give them space, to let them develop to the point where their expertise matched her own.

Authentic leaders don’t imply they have the last word. Instead, they recognize that their job is to bring out the best in others, and they hold themselves accountable for doing so. This requires showing respect for their colleagues — not just as professionals but as human beings.

You communicate that respect in small, unspoken ways. One of the most important is to always hold something back. Get into the habit of leaving some of your own thoughts and opinions unsaid, to make room for the participation of everybody else. This has the added benefit of giving you more opportunities to learn.

Even salespeople need to internalize this. Your job may be transactional, but your behavior shouldn’t be.

I work with many people who pitch for investment. I’ve learned to tell them, “Never be closing.” Don’t go into an encounter with the intention of finalizing the deal that day. You will give people the feeling that the deal is more important to you than the relationship, and those people will not trust you. Customers buy more from those they trust.

When you hold something back, you also take some pressure off your listeners. It shows that you have the intention of building a relationship, regardless of any particular transaction. If today’s deal doesn’t close, there will most likely be other opportunities, because the relationship is one of trust.

9. Investigate your impact

I was once asked to advise the CEO of a rapidly growing tech company on how to help his top leadership team overcome some very difficult personality clashes. The company had begun as an idealistic startup, and people still trusted one another’s intentions, but they blamed each other for some recent mishaps. The CEO was the harshest; he blamed everyone but himself. Though everyone liked him personally, his way of handling relationships was one of the toughest issues the company faced.

So I went to the data. I asked the CEO to come up with 10 words that he felt described the company’s culture. His choices were positive: collaborative, safe, trustworthy, and so on. Then I asked the other leaders to anonymously rate, on a scale of one to 10, how well each of those attributes described their company. The responses were much less positive. My client was shocked; he thought he knew his people well, and that their responses would be very different. He also finally took responsibility for rebuilding trust, starting with a new HR initiative to assess, anonymously, how people felt about the top team and the company.

Leadership is intangible, but there are always ways to study its effects, on yourself and your people, in the moment and over time. This requires raising your awareness through a variety of means: your own conversations, independent surveys conducted by others, and performance-related metrics that reflect responses to what you (and other leaders) say and do.

Technology has begun to augment these insights with techniques such as social network analysis. By mapping the path and frequency of communication, a social network researcher can identify important relationships. But as we saw with performance appraisals, you will never get enough insight from the analytic measures alone.

In the absence of definitive measures of leadership, can you look past your own biases and limited information to make the right choices? Can you be enough of an authentic leader yourself to recognize the same quality in others — and make your decisions about them accordingly? Can you do so reliably? Can you also make decisions about your own growth and conduct, based on a compassionate reading of your leadership presence? Developing this type of awareness is part of your path as a leader.

10. Build your “muscle memory”

All truly authentic leadership is improvisation. You come up with the right thing to say and do in the moment — not casually, but based on long experience, training, and insight. I learned this as a production assistant in a theater where jazz legend Max Roach played one night. He was known for his gift of improvisation, but he rehearsed on the drums relentlessly before his performance. He chanted as he played: “You’ve got to be in before you go out.” After an hour of this, he turned to me and said: “Do you know what that means? You have to know how far you can go out before you have to come back in.”

Leaders in the performing arts understand how much preparatory work is involved in improvisation. Yes, you are acting in real time, responding immediately to events, and sometimes setting a new direction on the fly. But it is impossible to do this successfully, as a leader in business or anywhere else, if you do not have enough experience and understanding to know, as Roach put it, when to go out — when to take risks — and when to come back in.

I often use the term muscle memory to refer to the quality you cultivate as an experienced leader — the quality that allows you to improvise successfully. It’s analogous to a specific kind of resilience that professional athletes are known for. When they are injured and must withdraw from play for a few months, they recover more quickly than an equally strong amateur would, because of their ingrained sense of where and how to focus their strength and dexterity. If you’ve played a sport for any length of time, you’ve experienced this: It’s as if the muscle itself understands what to do, and takes over, giving you a sensation of whether or not you’re doing it right. In tennis, for example, you can feel when your stance is correct, and when you hear the pop of the ball on the racket, that knowledge is confirmed. In turn, the feeling you get from the sound of the ball hitting the sweet spot can permanently improve the way you play.

Your leadership presence can be supported by a similar pattern of mental and emotional muscle memory. And because leadership involves the body, mind, and emotions, muscle memory is an apt way to refer to it. With enough practice, it can become second nature for you to address a group or a meeting in an authentic, authoritative way. Building this type of leadership presence will help you be resilient. Even in a crisis, it will help you focus on what’s happening right now, respond as the moment requires, and recover more effectively.

All 10 of these principles involve taking what is human and focusing and intensifying it in the service of a larger goal. The great choreographer Martha Graham understood this. As she famously said to her biographer, Agnes de Mille, "There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open." If your goal is authentic leadership, then this kind of expression is your business as well.

Author profile:

- Annette Kramer is a leadership coach who works with enterprises, startups, universities, governments, and not-for-profits on aligning organizational strategy and communication. She taught theater at Brown University and is a fellow at St George’s House, Windsor Castle, a think tank established by Prince Philip. She is based in London.