Adapting to a new world

Facing the challenges of the post-COVID-19 landscape.

A version of this article appeared in the Autumn 2020 issue of strategy+business.

The COVID-19 pandemic has wrought enormous personal, economic, and social damage. It has upended countless lives, and exacerbated the many disruptions afoot, laying bare the unviability of many business models. Beyond that, it has provided a new set of acute shocks to seemingly sturdy businesses and principles that have guided our thinking for decades. Wrapping our minds around what is happening is enormously difficult. Having resulted in 4.2 million known infections and 287,000 known deaths as of May 12, the new coronavirus is unpredictable and lethal, and its like hasn’t been seen in more than a century. Its effects are paradoxical. It has caused a supply shock and a demand shock. It is causing a recession of indeterminate length and severity — even as some countries are crawling their way back to recovery. It is inspiring heroic feats of public-spiritedness and charity among millions, while also providing an opportunity for fraudsters to peddle false cures and prey on the vulnerable. It is stoking competition among countries, and between regions within countries, to secure supplies, while also serving as an occasion for greater national solidarity and regional cooperation. The pandemic is primarily a public healthcare problem, but one with immense immediate implications for business, and for economic, fiscal, and monetary policy. The health threats could disappear within a matter of months — or they could persist for years. This virus is both accelerating powerful existing trends (such as automation and inequality) and slamming the brakes on trends that had, until very recently, possessed tremendous momentum (such as globalization).

Out of nowhere, COVID-19 has emerged as the top agenda item for leaders of organizations of all types: governments, NGOs, and the private sector. The central question in every (virtual) board meeting is how to grapple with the horrific short-term consequences — the health challenges faced by millions of people and the effective shuttering of economies and societies around the world. At the same time, leaders can’t lose sight of the existential difficulties they faced before discussions of viral loads, reagents, and recovery rates became part of the vernacular — difficulties that, if anything, are intensifying.

The scope of the challenges, with all their dimensions, is as much philosophical and intellectual as it is physical and practical. Simply put, we are wondering how to go about restarting the economy; repairing what was broken; and preparing ourselves to cope with a host of urgent social, environmental, demographic, and economic troubles.

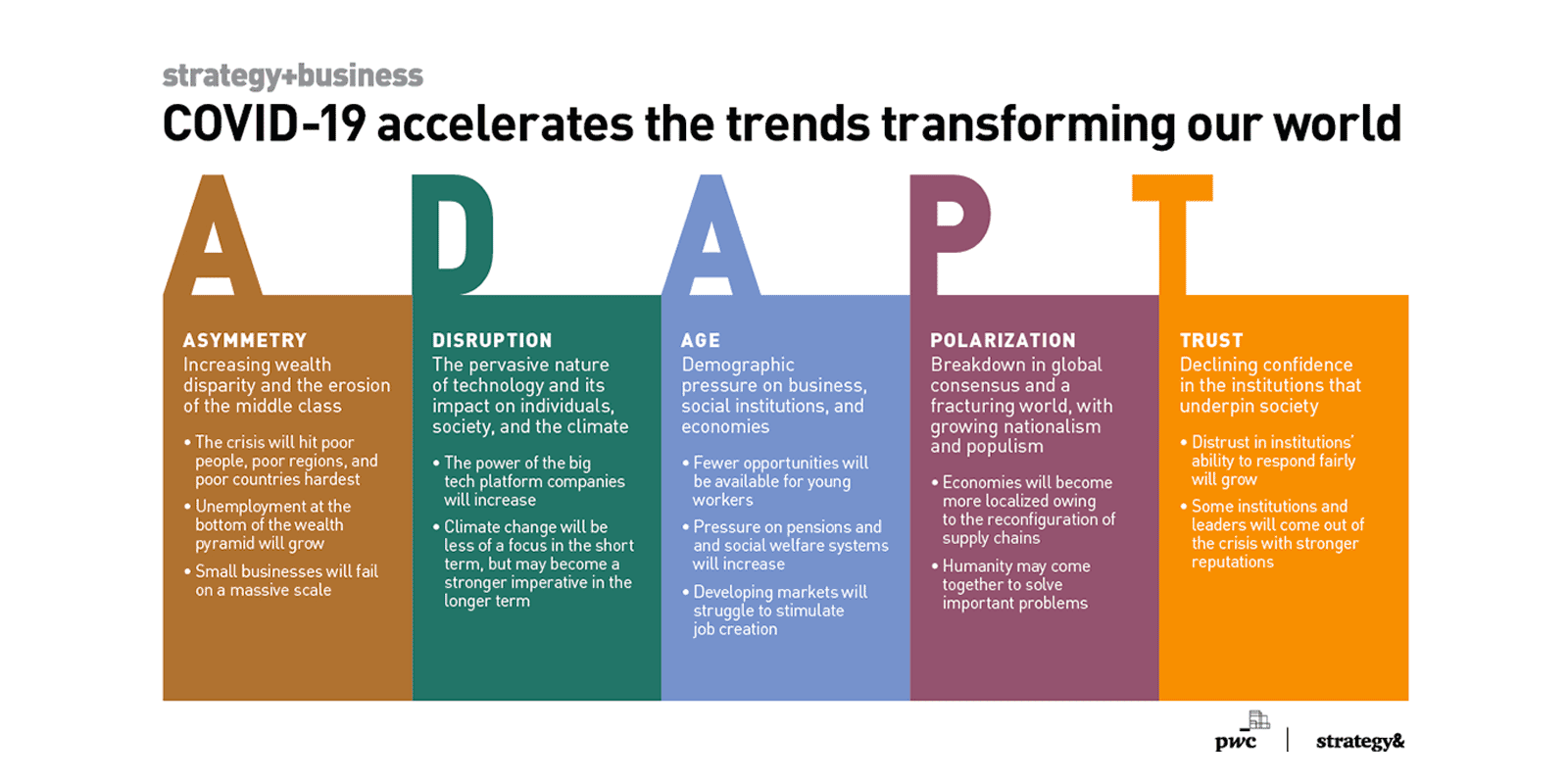

At PwC, we have been thinking about how to approach these issues holistically. In 2017, we identified a set of urgent, interdependent, and accelerating challenges confronting the world. We dubbed it the ADAPT framework — describing a world in which asymmetry, disruption, age, polarization, and trust were fundamentally changing the way millions of people live and work. It was clear before COVID-19 that the pressures arising from the ADAPT issues would forge a completely different world by 2025, and that organizations would have to reconfigure themselves to maintain their viability. Accelerated by the pandemic, these changes may actually come about sooner than we thought (see “ADAPT + COVID-19”). In our forthcoming book, we predict that humanity has “10 years to midnight.” Now, it seems there may be even less time to the fateful hour. Moreover, COVID-19 will not be the last such shock to the system. Unless we massively and quickly address the issues highlighted by ADAPT, and in a way that manages the crisis of today while preparing us for the future, the next shock will be much more damaging. That’s the bad news. The good news? At every unit of analysis and level of society, there is an opportunity to build a more sustainable and resilient future in which all people can thrive. By recognizing the challenges confronting the world, internalizing the lessons of the pandemic, and deploying the tools and technologies at hand, we can chart a new, more adaptive course.

(Story continues below)

ADAPT + COVID-19

Asymmetry. The world has been riven by a growing disparity in wealth among individuals, regions of countries and the world, and generations. As a result of COVID-19, wealth disparity will increase at an accelerated pace. Inequality between nations will grow as the choices leaders make in navigating the crisis and the varying severity of its impact extend the differentiation between countries and regions emerging from the pandemic. Disparity within nations also will increase as small businesses fail, unemployment rises, and those at the bottom of the wealth pyramid suffer disproportionately, as typically happens during recessions. Existing regional disparities between thriving areas and those starved of capital will be exacerbated, as resources available for investment decline. On the demographic level, three groups of people were at risk before COVID-19: the soon-to-retire who were already under-resourced, young people about to enter a weakened job market, and midcareer workers with financial obligations who couldn’t afford to lose a job. To these cohorts, we add a fourth: those who were just barely managing, who will now be pushed off a cliff as they cannot pay for housing, food, or other basic requirements of life.

Disruption. Technology and climate change are remarkably powerful and interlinked disruptive forces whose signals will be amplified by COVID-19. The power and influence of the big tech companies and other organizations with platform business models will likely grow. Through quarantine and self-isolation, many of us are being forced to socialize and work primarily via technology. We are streaming entertainment, shopping online, and mitigating the downsides of isolation by staying connected to friends and family via technology as well. Whether it’s telework, streaming video, or e-commerce, much of this activity flows to the largest players, which are reaping a return on scale. In the first quarter of 2020, for example, Netflix added 16 million new subscribers — almost twice the number it added in the fourth quarter of 2019. The pandemic is also likely to accelerate the automation of jobs through AI and robotics (which don’t require social distancing). As the Brookings Institution points out, bursts of automation in industry tend to happen as employees become relatively more expensive during big revenue drops.

Climate is still the most important disruption facing humanity and the planet. The very urgent issues arising from climate change — and related crises, such as dramatically reduced biodiversity — will not recede even if emissions momentarily fall as a result of reduced economic activity. On the one hand, the economic crisis following the COVID-19 pandemic risks distracting people’s attention and diverting planned investments aimed at fighting global warming. Investment in alternative energy sources is expected to decrease as government and business leaders focus on short-term exigencies and oil prices fall to historically low levels. On the other hand, as governments retool their economies, it is possible that they will put climate-mitigation efforts at the front of their initiatives, as South Korea has. Also, people may be more attuned to the possibility of natural hazards, and that could strengthen their desire to mitigate those hazards’ effects.

Age. The challenges that aging populations pose to some sectors — such as inadequate healthcare systems — have accelerated and are now at the heart of the crisis. The pandemic will have a differential effect on distinct age groups, changing the outlook for many people’s lives. The world is dividing into countries in which a large percentage of the population is nearing retirement age, resulting in added pressure on social and health systems, and countries with a majority of their population approaching working age, requiring the creation of educational capacity and new businesses and jobs on a massive scale. Countries with young populations will face a crisis as a depressed economy provides fewer jobs and lower wages for the growing pool of people looking for work; in Egypt, for example, those aged 18–29 (19 million people, or one-quarter of the country’s population) had an unemployment rate of more than 30 percent before COVID-19 hit. On the other end of the demographic scale, pension pots and retirement savings and investments will be diminished and thus some people may be unable to retire, or will require more support in retirement than government economic models currently assume.

Polarization. The world started fracturing long before the pandemic struck, as citizens’ faith in institutions and leaders was breaking down, disparities were growing, sharp divisions led to a failure to communicate effectively across divides, and multilateral institutions labored to maintain traction. COVID-19 has only intensified these trends. The World Health Organization is struggling to be effective and maintain its funding, even as a number of countries without sufficient resources depend upon it and similar institutions. The rush for vaccines and medical supplies has spurred countries to withdraw from economic cooperation, and a widespread reassessment of global supply chains is underway. There is a possibility that as we emerge from this crisis with a shared experience, humanity will start to work together again. But in the short term, local concerns will become more acute and international alliances will be put under new strain.

Trust. Trust in government, civil society, business, and the institutions that make our societies work had already declined dramatically, especially among those not in advantaged positions. This reduced trust in institutions is complicating efforts to deal with the crisis. In many places, people are refusing to abide by social distancing recommendations or are questioning the utility of vaccinations. As citizens watch this pandemic continue to unfold, leaders have the opportunity to build trust or destroy it further. The more people fear that systems will fail them and lose hope that they will be better off tomorrow, the more the already-brittle bonds of trust will fall asunder. The situation begs for a new set of leaders more cognizant of the world we now live in.

COVID-19 and the economy

Efforts to address these issues that are made even more urgent by the pandemic face four harsh realities.

First, at both a national and a corporate level, balance sheets will be tremendously stretched and require significant shoring up before resources become available to address the issues outlined in the ADAPT framework. According to the Institute of International Finance (pdf), “If net government borrowing doubles from 2019 levels — and there is a 3 percent contraction in global economic activity (nominal terms) — the world’s debt pile would surge from 322 percent of GDP to over 342 percent this year.” There will be intense competition for funds as societies focus on the many tasks associated with restarting businesses, creating jobs, and supporting those most harmed by the pandemic and the national response. At the corporate level, limited capital will necessarily be focused on repairing damaged supply chains, restarting the business, rebuilding revenue, and bringing employees back into place.

Second, small businesses will be even more significantly affected than larger ones by the policy decisions made. The impact will vary across countries because of the very different ways governments are responding to the crisis. Across the world, however, most small businesses do not have the kinds of cash reserves larger companies do; according to a study (pdf) by JPMorgan Chase, the median U.S. small business holds only 27 cash buffer days in reserve, after which it would have to be shuttered without cash inflows. This is a particular problem as small business is generally the most important source of employment and disproportionately the source of growth. But it is also a problem for larger organizations, because small businesses are most often primary customers and a third or fourth tier in their supply chain. Small businesses also provide essential services, such as equipment maintenance and repair, dentistry, and, in some economies, basic foodstuffs.

Third, different sectors of the economy — and even individual businesses within the economy — will be quite differently affected by the crisis. Platform companies, grocery stores, and pharmacies have, for the most part, done extremely well so far. But many others (e.g., airlines and hotels) have largely shut down. All except the hardest-hit firms are trying to maintain their workforce; the result is that they burn through cash and end up in a much more precarious financial position. Clearly, firms with stronger balance sheets will be able to build back or sustain their business more easily, while many others will struggle. Decisions made about when to begin and how to end the lockdown, coupled with financial relief packages, will cause businesses in some countries to be better positioned to weather the crisis and recover afterward. The dispersion of outcomes could have a radical impact on a nation’s influence at a global level and how that nation is able to compete on the international stage in the future.

Finally, unemployment has grown in many markets. In the U.S., more than 30 million people had filed for unemployment by the end of April. The International Labour Organization noted in its April 29 monitor of COVID-19 impacts on the world of work that “almost 1.6 billion informal economy workers (representing the most vulnerable in the labor market), out of a worldwide total of two billion and a global workforce of 3.3 billion, have suffered massive damage to their capacity to earn a living.” This figure represents both a devastating human cost and an additional burden on countries with already growing fiscal challenges. For businesses, unemployment will affect the ability of the consumer base to buy goods or services, pay rent, and repay debt.

An effective response

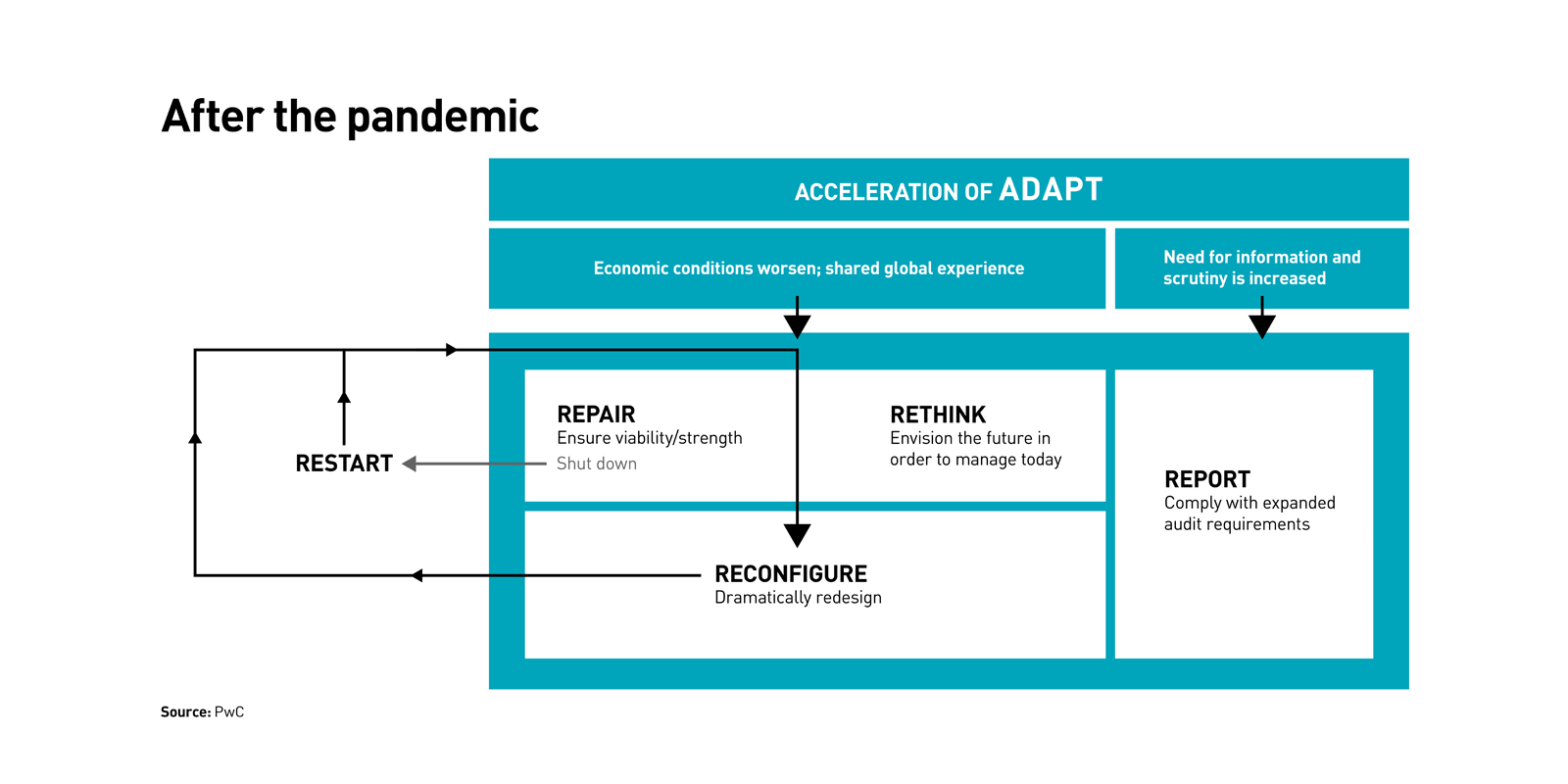

The scale of the problems may seem daunting. But that is no excuse for inaction. For governments, businesses, and institutions, the essential elements of a high-level response are quite similar (see the diagram below). We need to be highly cognizant of the choices we are making today, because they will dramatically affect our ability to accomplish the essential actions that constitute the response.

Repair. The overriding short-term imperative is to fix what has been broken. This starts with balance sheets. As governments repair the human and economic damage, they are coping with increased national debt, a reduced tax base, and higher short-term spending. They will also have to repair the damage done to the personal balance sheets of citizens, whether those are older people who have suffered significant losses in retirement funds or younger people who were just getting by and have been pushed into far more difficult circumstances. Governments will need to manage national costs, shore up revenue, and find ways to accelerate business growth and related new skills development. The success of these repair efforts will determine how long the effects of this crisis extend over the years. And, make no mistake, it will be a slog. It took a decade for most of the world to rebound from the financial crisis of 2007–08, and some countries and parts of society have yet to recover. The level of debt accrued during the initial pandemic response far exceeds the total stimulus during and after the financial crisis. In March alone, the U.K. enacted £65.5 billion ($81.6 billion) of stimulus, compared with the £42 billion ($52.3 billion) it mobilized to fight the financial crisis. The deeper the hole, the more work and time it takes to fill it.

For their part, businesses will need to address vastly weaker balance sheets, steep revenue declines, and, in many cases, weakened supply chains and stressed or depleted employee bases. Each of these elements will require triage, lest the organizational difficulties persist and erode any real chance of a speedy recovery. And in many instances, attention and resources will be focused on triage for a long time. Some firms will emerge from the pandemic in relatively good shape and thus be in a position to take advantage of opportunities arising from the challenges confronting the rest. However, in some cases repair efforts will fail and lead to bankruptcy, or even liquidation, because the company’s preexisting condition was too feeble, or because it couldn’t execute an effective repair strategy. Again, clear decision making and decisive action based upon a real understanding of what is essential to the world after COVID-19 are critical.

Rethink. This element is conceptual and provides the context in which the decision making of the repair efforts needs to happen. People around the world are sharing a deep and worrisome experience. Conditions will be fundamentally different when we emerge from the pandemic. Every nation and organization needs to reimagine the future at both a practical and a conceptual level. Organizations and their leaders need to force themselves to be strategic at a time when they are grappling with an intense crisis and coping with day-to-day emergencies. Redesigning a boat while bailing water from the hull may sound ambitious. But it is necessary, even compulsory.

The good news? At every unit of analysis and level of society, there is an opportunity to build a more sustainable and resilient future.

Rethinking starts with the practicalities. Both governments and businesses need to review how they responded to the pandemic, understand best practices, and prepare for the next inevitable crisis. It will be impossible for our systems to cope with the next challenge if they remain in the same fragile state in which they entered this one. The next step is to quickly begin reimagining and adapting strategy for a post-COVID-19 world. If they weren’t doing so already, companies need to rethink their operating models so that they can be robust enough to handle the disruptions arising from ADAPT. How do they construct supply chains that can function in a world in which international transport may be shut down and in which emissions are limited? And how do they design their business model so that it can be sufficiently flexible to evolve as circumstances change?

Countries and companies will be positioned very differently as a result of this crisis and thus will need competitive and collaborative strategies that are dramatically different from those they might have imagined a few months ago. Countries need to consider what is essential to localize for reasons of security, economy, and crisis management. More broadly, both nations and organizations need to rethink what success means. Gross domestic product and earnings per share have been our lodestars for decades. But we clearly need new measures of material, social, and environmental progress that can guide our efforts. Lastly, how do we create the adaptive capacity essential for addressing the unforeseen issues that are sure to be propelled to the surface by the pressures of the ADAPT forces? Rethinking ensures that organizations are repaired in a way that makes them more resilient and more successful by bringing considerations about the future into the present.

Reconfigure. Organizations must make the systemic rethinking concrete by reconfiguring public and business institutions. This represents a much more fundamental redesign of organizations than the repair process entails. The crisis has put into strong relief the uncomfortable truth that a host of institutions around the world are simply not ready for the 21st century. It is essential that systems including healthcare, legal, education, taxation, and others be reconfigured to be more efficient, more effective, and more able to cope with the ADAPT challenges.

What does this mean in practical terms? To address the asymmetry inherent in the global economy, governments will have to accelerate the development and scaling of small business on a massive scale. To confront the disruption of climate change, governments and businesses alike will have to re-envision energy and climate policy and make investments to reduce their carbon footprint — which will have the salutary effect of providing investments for new jobs. To a degree, reconfiguration also means jumping on the trends that have suddenly gained currency in response to the pandemic, including telemedicine, distance learning, and remote working. But it means approaching issues such as the localization of supply chains on a systematic basis, rather than an ad hoc one.

Companies not ready for a platform-based economy — one in which business transactions and social activity are largely facilitated by digital platforms or frameworks — need to become ready quickly. Organizations need to rethink technology strategy, geographic footprints, and business models to make them more robust and to recognize the very strong pressures for localization they are going to experience. They will need to evaluate their portfolios from the standpoint of the products or services needed in a very different economy. Like governments, organizations should not let opportunities arising from the crisis go to waste and should undertake significant reconfiguration in a manner that sets them up for an even better future.

Reconfiguration may be made easier because COVID-19 has provided a rare moment of pause, an opportunity to make changes that previously seemed too daunting or even impossible to execute. However, the challenge is that organizations are carrying out structural changes with fewer available economic resources, and there is always the chance of another major disruption. New legislation could alter business plans, or the disease could swiftly worsen in a country that is critical to the organization’s supply chain. Failure during the reconfiguration process is still possible, although less likely than during the repair phase.

Report. In the midst of the pandemic, there has been a constant search for clarity — on what measures individuals should take, on the availability of testing, on how we construct a path forward. In a period of great uncertainty and invisible threats, people feel comfortable going about their lives only if they are confident in the information they receive. Investors, regulators, and stakeholders will also be demanding more disclosure and information in real time on everything from cash flow to the health of employees. Emerging from this shared, transformational experience, people may be more conscientious and thoughtful, and will desire more transparent information on a broader range of issues, both to permit the changes suggested above and to have the right to be in business or lead. To take a simple example, all businesses will have financial risk. What will be required by investors, regulators, employees, customers, and the general public is much more specific data about the real risks to the government and businesses, the specific plans to address those risks, and the viability of the plans. Industries that received special support from government are likely to be under greater scrutiny. Stakeholders will want ongoing reports on the success of execution against their targets.

Transition to a new world

The need for governments and organizations to transition to a new world was apparent well before COVID-19 arrived. The pandemic and the associated economic, organizational, and personal consequences of the decisions made to address it just made the need for those transitions greater and, in an odd way, better prepared us to make the necessary changes. It would be unfortunate — and potentially devastating — if we did not take advantage of the opportunity in front of us.

It is essential that we not regard the two immense sets of challenges we face — the deeper issues the world is confronting articulated in the ADAPT framework, and the immediate economic consequences of the steps countries are taking — as competing for attention and resources. Instead, we must find a way to reduce disparity, address the major threats presented to our well-being by climate change and the unintended consequences of technology, manage the lack of prosperity for the youngest and oldest generations, build a greater sense of social cohesion, and rebuild trust in the institutions that make society work at the same time we rebuild our businesses, our work, and the lives of our citizens. We should not lose the potential benefit of the natural reflection everyone is now beginning to go through: to create the world we want to have, not just reestablish the world we had before. If ever there were a time for leadership, it’s now.

And we should expect that the strategic response to COVID-19 will open up new possibilities. One of the remarkable features of this pandemic is that it has created a shared global experience of an overwhelming event. Although personal situations vary greatly, almost everyone can relate to the concerns of a rapidly developing problem; the moments of fear alongside moments of peace and awareness of personal good fortune; the acute pain of feeling concern for loved ones while not being able to be physically present; coping with restrictions in movement; and suffering harm from the disruption to one’s normal routine or the loss of a job, company, family member, or friend. If this shared experience can engender greater solidarity and a sense of purpose, the prospect of adapting to a new world and thriving in it becomes more promising. Hope is not a strategy. But strategy can provide hope.

Author profiles:

- Blair Sheppard is the global leader of strategy and leadership for the PwC Network. He is also professor emeritus and dean emeritus of Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. He is based in Durham, N.C.

- Daria Zarubina is a member of the global strategy and leadership team at PwC. Based in Moscow, she is a director with PwC Russia.

- Alexis Jenkins is the chief of staff for the global strategy and leadership team at PwC. Based in London, she is a director with PwC UK.

- Thomas Minet, a director with PwC US and a member of the global strategy and leadership team, also contributed to this article.