That same old song is becoming a new value differentiator

With the growth of digital streaming, torrid demand for the pop catalogs of yesterday is providing a new means of value creation for the entertainment and media industry.

A version of this article appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of strategy+business.

Neil Young famously thumbed his nose at the commercialization of pop music in his 1988 song “This Note’s for You,” in which he declared he “don’t sing for nobody / Makes me look like a joke.”

But the legendary singer-songwriter appeared to change his tune last January when he sold a 50% interest in his 1,180-song catalog to Hipgnosis Songs Fund. Within months of the deal, the UK-based music IP-investment and song-management company had licensed Young’s “Old Man” for the CBS series The Equalizer and “Harvest Moon” to Netflix comedy Sex Education, according to Hipgnosis’s annual report.

Sellout or not, Young had impeccable timing.

Producers of ads, movies, TV, and Broadway and Las Vegas shows, as well as countless products, games, digital streaming services, and devices, can’t get enough of old music hits, especially from the 1960s and 1970s. The recent surge of high-priced deals for the right to license music and lyrics from legends including Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Prince, Burt Bacharach, and Stevie Nicks has made song catalogs one of the most valuable asset classes in the entertainment industry.

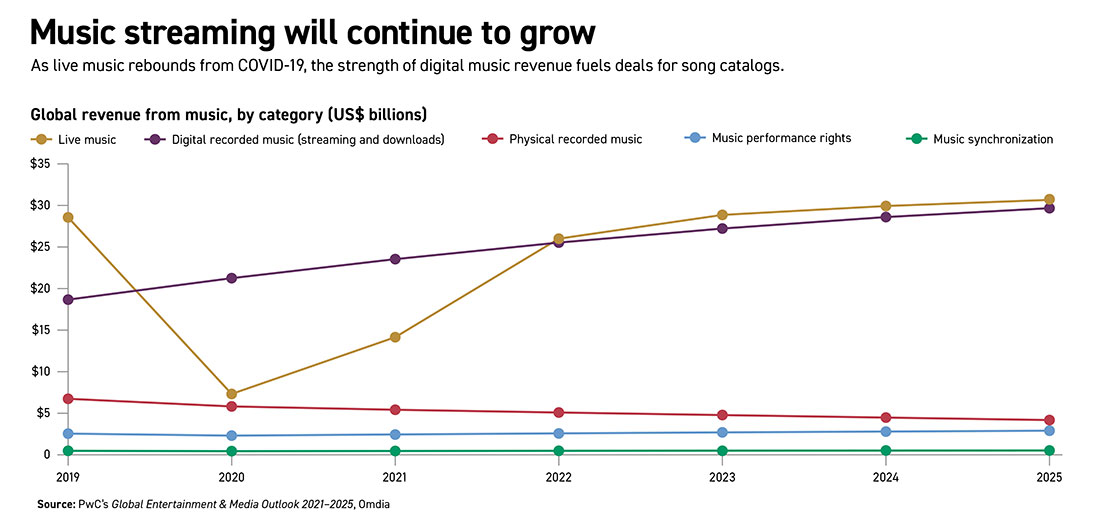

Now that streaming-music services have all but erased fears that online pirates will decimate the music industry, the same old songs have even more value—offering, as Aaron Siegel, Goldman Sachs’s global head of entertainment investment banking, put it, “bond-like risk with equity-like growth.” Global consumer spending for audio streaming will rise 32% over five years to US$24.8 billion in 2025, PwC forecasts in its Global Entertainment & Media Outlook 2021–2025. Ad sales for streaming will add $4.4 billion in 2025, also up 32% in the period.

Against this appetite for audio content, it may not be surprising that classic pop song catalogs are attracting fevered interest. With the growing reach of audio streaming and prominence of digital creators on TikTok and YouTube, the earworm songs of old are proving to be a fulcrum of strategy development for a new era. This boon is especially welcome in a sector that has been under pressure from the forces of digital disruption to embrace change.

Oldies but goodies

Indeed, seeing the new value potential at stake, music corporations around the world are anteing up big money for classic pop catalogs, sometimes just to market a handful of memorable tunes.

Universal Music Group, which went public in September 2021, reportedly paid Bob Dylan about $325 million for his catalog, while Sony Music Publishing, the industry’s largest publisher, paid an estimated $250 million for rights to Paul Simon’s songs. Primary Wave Music paid a reported $100 million for an 80% stake in Stevie Nicks’s compositions and struck deals for interests in songs by Burt Bacharach, Olivia Newton-John, and the Four Seasons.

And Hipgnosis is after more than just Neil Young classics. The company paid nearly $323 million for Kobalt Music Copyrights’ portfolio of more than 33,000 songs from writers including Lindsey Buckingham, Steve Winwood, and Mariah Carey. From the time the company appeared on the London Stock Exchange in 2018 through March 2021, Hipgnosis spent $1.94 billion for 138 catalogs with 64,098 songs.

Apollo, one of the biggest private equity firms, backed music executive Sherrese Clarke Soares, to the tune of $1 billion, to go acquire music assets.

Though dealmakers don’t always disclose terms of their transactions, industry executives say that at least a few high-profile catalogs have sold for more than 30 times the revenue they generate in an average year. That’s up from a multiple of five times average revenues typically paid a little more than a decade ago.

These numbers are music to the ears of catalog owners—especially performers looking to retire or make up for concert revenues they lost during the COVID-19 pandemic. A few also hope to beat proposed rate increases for federal capital gains taxes, which catalog owners must pay when they sell.

They’re under no illusion that old songs will return to the top of the charts—although a few may surprise. For example, Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 hit “Dreams” awoke to a new life last year after an Idaho man became a TikTok star with a video of himself on a skateboard lip-syncing the song.

“I was an advocate of ‘Hold on, these are your annuities and legacies,’” says Tina Fasbender, whose firm, Fasbender Financial Management, advises songwriters. “But the landscape changed.”

Copyright owners collect when young hitmakers sample or remake tunes, often ones that were popular long before they were born. Last year, singer Doja Cat’s “Freak” sampled Paul Anka’s 1959 hit “Put Your Head on My Shoulder.” In 2019, Ariana Grande incorporated “My Favorite Things” from the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The Sound of Music into her hit single “7 Rings.”

Pop classics also excel in licensing deals for products or productions. They’re among the few cultural artifacts that appeal to listeners across age groups, national boundaries, and deeply polarized cultures.

Even incidental connections can be valuable. When you go to a home game for football’s Pittsburgh Steelers, you’ll find Voodoo Brewing Co.’s “Oh Mama” beer—the name taken from the opening lyric of Styx’s 1979 song “Renegade,” a team anthem. And grocery store shelves are filled with General Mills’ new limited-edition “Monster Mash” cereals, harking back to the 1962 hit by Bobby “Boris” Pickett & the Crypt-Kickers.

“We are outpacing organic [music industry] growth by about 8% because of all our value-enhancement initiatives,” says Reservoir Media CEO Golnar Khosrowshahi, whose company licenses “Monster Mash” to General Mills. Reservoir, which went public in 2021, recently won the right to administer songs from Joni Mitchell, Alabama, Billy Strayhorn, John Denver, Sheryl Crow, and Rickie Lee Jones. “It is an important part of what we do.”

Seeing the new value potential at stake, music corporations around the world are anteing up big money for classic pop catalogs, sometimes just to market a handful of memorable tunes.

PwC expects music synchronization sales, royalties from songs incorporated into other works, to grow 13% to $520 million between 2021 and 2025.

Some buyers are more bullish, such as Primary Wave Music CEO Lawrence Mestel, who recently bought a major stake in Prince’s estate and is working on Broadway shows featuring works by Whitney Houston, Smokey Robinson, and Burt Bacharach, as well as a show for a Las Vegas casino with the music of reggae superstar Bob Marley.

“Prince is going to be significantly more valuable 10 years from now than he is today,” Mestel says. “He has a vault of thousands of unexploited masters and videos. There’s never been a Broadway show or a biographical film or very much organic exploitation of Prince and his brand. There’s so much to do that the fans would crave.”

From “Heart of Gold” to gold rush

But not all pop catalogs are created equal. As Mestel observes, recording artists with new or recent hits might look attractive because they’re making a lot of money now, but those revenues are expected to decline as the songs lose their cachet. There’s no guarantee that they’ll have lasting value as classics. “When you buy things that are too new, you’d better pay a low price because the revenue stream is coming down,” he says.

Goldman Sachs’s Siegel says he isn’t worried yet. “Every generation is skeptical about the new generation’s music. New generations always create standards and classics. I have full confidence that this generation’s music will continue to resonate and stand the test of time.”

Regardless of era, the scorching demand for pop catalogs might not last.

“The top [of the market] is coming,” Fasbender says. That has led to delicate conversations with clients eager to collect the kinds of valuations Bob Dylan and Neil Young commanded. “You can’t say to someone, ‘Your catalog isn’t worth that.’”

Put another way, those betting on the future of pop catalogs need to consider: how will their decisions hold up, as Young might put it, after the gold rush?